Exploring the link between our health and ecosystems

The deadly Covid-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, drove scientists to start thinking more analytically about the ever-intensifying interactions between humans, animals and the natural world.

Coupled with the equally intensifying impacts of climate change, scientists called for the adoption of a ‘One Health’ approach to the Covid, and future pandemics, based on the simple premise that human health and the ecosystems they share are inextricably linked.

According to the One Health approach, the health of the ecosystem cannot be separated from the health of all humans, animals, plants, and their living environments.

From UN agencies, to academia, international and national development agencies to governments worldwide, to media and indeed, many of the world’s citizens, the inter-connectedness of human, animal and environmental health is today widely recognised.

Taking a ‘One Health’ transdisciplinary approach was lauded as the solution to Covid and future pandemics.

Institutional response

The terminology ‘One Health’ dates back to the nineteenth century. It was recognised by Dr Rudolph Virchow (1821-1902), a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor and politician working on human and veterinary medicine.

The idea took root in the 1960s and received renewed attention in the 2000s, with the emergence of SARS and a highly pathogenic variety of bird flu.

The problem about ‘One Health’, experts point out, is that the broad scientific consensus around the concept has not led to a corresponding institutional response, at least not on the scale that is necessary. Medical and veterinary authorities too often still operate in separate domains.

“Our health systems still divide the world into neat categories: doctors take care of humans, veterinarians of animals, environmentalists of ecosystems,” the then Director-General of the Nairobi-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Dr Jimmy Smith, wrote in an opinion in The Independent on February 26, 2020.

He proposed various remedies such as more surveillance and monitoring of animal diseases, better vaccination and food safety programmes, and more work on the broad array of issues that arise out of the interactions between people and animals. These include antimicrobial resistance, foodborne diseases and poor animal health.

Covid brought severe health and economic consequences worldwide, whose repercussions are still being felt today. The ‘One Health’ approach is a way to understand and address the interconnectedness of human, animal an environmental health.

Climate change impacts all three of these areas, creating new challenges for human health. So, where is the interconnectedness between climate change and ‘One Health’?

Extreme events

Climate change can create new opportunities for diseases to spread between animals and humans. It can also disrupt food systems and increase the risk of food, water, and vector-borne diseases.

Climate change can lead to more frequent and severe extreme weather events such as heatwaves, storms and floods. It can also cause mental health issues.

How does the ‘One Health’ approach help in addressing these issues? Scientists say the ‘One Health’ approach helps by encouraging collaboration between veterinary, medical, and public health professionals.

The ‘One Health’ approach emphasises the importance of interdisciplinary research to understand the impacts of climate change on health. It encourages action to address climate change, such as taking action on clean water, energy and air.

What can be done to address the impact of climate change on ‘One Health’? Experts say this can be achieved through transdisciplinary participation in national health impact assessments.

The impact of climate change on ‘One Health’ can be addressed by the facilitation of transdisciplinary coordination in areas such as renewable energy, infrastructure and urban design. There is also need to engage in official national missions and international legislative events related to climate change.

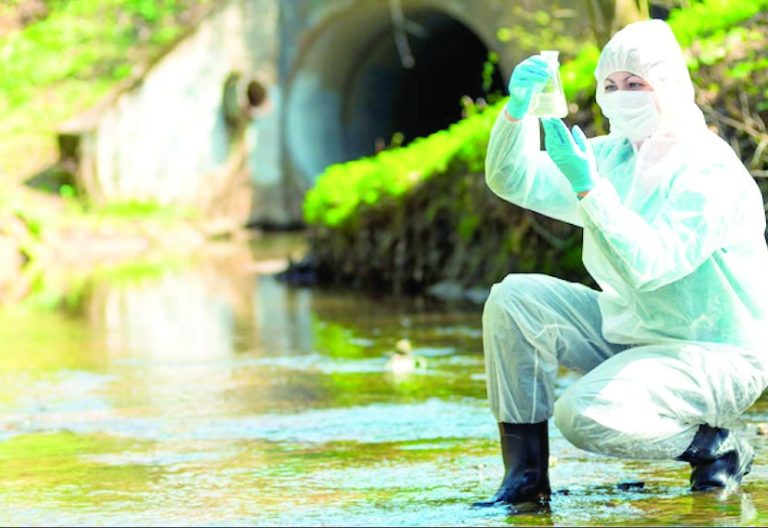

Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) is an essential component of public health and the ‘One Health’ approach. Inappropriate animal and human excreta management can contribute to both pollution of the environment (water and soil) and the spread of antimicrobial resistance, hence the need to have it managed jointly.

Climate change leads to more frequent periods of high precipitation, causing an excess in runoff and associated wash-off of human and animal faecal matter containing zoonotic pathogens.

This can be from manure-fertilised fields or open defecation, to surface and drinking water sources, all potentially increasing the risk of disease outbreaks.

The impacts of climate change on human health are not limited to the increase in average temperatures and the melting of glaciers. Climate change is also the cause behind human and animal migration, the increase in extreme weather events, the emergence and spread of vector-borne and waterborne infectious diseases, and rises in allergens, air, water and food pollution.

An increase of 2-3 degrees Celsius in global average temperature will affect the migration pathways of mosquitoes, increasing the population at risk of malaria by 3-5 per cent.

The number of emerging infectious disease outbreaks has increased steadily since 1980. Many infectious diseases, including HIV/Aids SARS, Ebola, rabies, salmonella and West Nile virus are transmitted from wildlife to humans.

Billions of people get sick and die from these viruses that are essentially environmental viruses. Protecting public health begins with the protection of environmental health and the adoption of the ‘One Health’ approach.

Disease transmission

Up to 75 per cent of new or emerging infectious diseases and 60 per cent of the known infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin. The World Health Organisation (WHO) designated the COVID-19 pandemic a zoonotic disease.

The primary route of COVID-19 transmission from animals to humans was believed to be zoonotic overflow. It is generally accepted that the virus originated in bats with an intermediate animal host, presumably a pangolin, contributing to the virus’ transmission to humans.

‘One Health’ issues therefore include climate change, zoonotic diseases, antimicrobial resistance, food safety and security, vector-borne diseases, environmental pollution and other health risks to humans, animals and the environment.

In addition, chronic illness, mental health, injury, occupational health and non-communicable diseases can be addressed with this approach that entails transdisciplinary cooperation.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, WHO Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told the 2020 World Health Assembly that the pandemic was a reminder of the intimate and delicate relationship between people and planet.

“Any efforts to make our world safer are doomed to fail unless they address the critical interface between people and pathogens, and the existential threat of climate change that is making our Earth less habitable,” he cautioned.

There is a link between ‘One Health’ and climate change migration. Climate change threatens access to clean air, safe drinking water, nutritious food and safe shelter of humans and animals alike. Rising sea levels, melting glaciers, extreme weather events, heatwaves, droughts, and wildfires are forcing more and more species to migrate.

Change in environmental conditions and habitats creates new opportunities for the transmission of diseases to animals and from animals to humans. Furthermore, the stress they experience to meet their need for food and shelter makes species vulnerable to viral diseases.

For food and water security, clean air, clean water and extreme weather events are also important for plants and agricultural products.

So much so that climate change is expected to cause 250,000 additional deaths per year between 2030 and 2050, with 144,000 due to viral diarrhoea and malaria and 95,000 due to childhood undernutrition.