Year ends well for vulnerable nations after COP29 summit

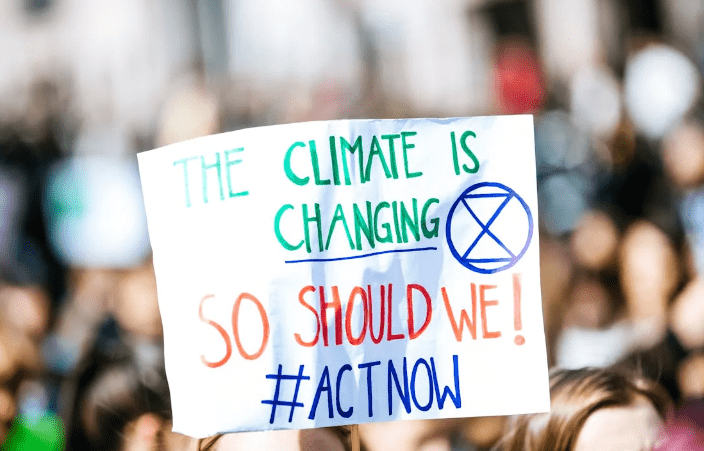

The year 2024 will be ending with a bang when it comes to international attention for climate change, barely a week after the controversial United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) in Baku, Azerbaijan.

After years of indefatigable campaigning for environmental justice, some of the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations finally have their day in court.

Countries and key stakeholders in the climate arena are meeting again at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague for much-awaited hearings on the obligations of states in respect of climate change.

A Pacific-led group of law students and diplomacy led by the island state of Vanuatu wants the ICJ to clarify what countries must do to address climate change and what legal repercussions they should face if they don’t and “significant harm” is caused.

Climate summits

The vulnerable countries have taken their battle to The Hague as they are fed up with zig-zagging the world to get climate summits like conferences of parties (COPs), usually coming away bitterly disappointed.

But at the ICJ, whose hearings continue until this Friday 13 December, high-emitting rich nations are shielding behind the very same climate treaties underpinning those talks to quash pressure to step up their climate actions, writes Isabella Kaminski in the authoritative UK-based Climate Home News.

Recent years have seen an increase in not only climate-related court cases but also a deeper engagement of legal scholars and judicial bodies with matters related to the environment more generally. Children, elderly women, and non-governmental organizations have gone to court to bring about enhanced climate action.

But first, what is environmental justice (EJ)? The UN General Assembly and the UN Human Rights Council recognised the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable development in 2022 and 2021 respectively.

The UN Development Programme (UNDP) has developed a global strategy for EJ to increase accountability and protection of environmental rights.

Environmental justice is a social movement and a set of principles that aims to ensure that all people have access to a healthy environment and equal protection from environmental hazards.

This includes the right to access natural resources, protection from environmental harm and the right not to be disproportionately harmed by environmental policies, laws and regulations.

EJ also includes the right to access environmental information and the right to participate in decision-making processes that affect the environment. Environmental justice seeks to address environmental inequities that can harm marginalized communities, such as those caused by hazardous waste, resource extraction, other land uses and redlining (discriminatory practice).

Fair treatment

In the US, the EJ movement was primarily started by people of colour. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines EJ as fair treatment of all people regardless of race, colour, national origin, or income. The Justice40 Initiative aims to provide 40 percent of the benefits of federal investments to disadvantaged communities.

Nature rights laws have been passed in various jurisdictions around the globe. The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea recently confirmed that states have to prevent, reduce, and control marine pollution from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and protect and preserve the marine environment from climate change impacts and ocean acidification.

Another advisory opinion is pending at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on the individual and collective obligations of states to respond to the climate emergency within the framework of international human rights law.

The ICJ, which is the only court with both general and universal jurisdiction, is expected to clarify states under international law to ensure the protection of the climate system and other parts of the environment from anthropogenic GHG emissions for states and for present and future generations.

Climate system

It is also expected to clarify the legal consequences under these obligations for states where they, by their acts and omissions, have caused significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment.

These legal consequences are with respect to in particular, small island states, which due to their geographical circumstances and level of development, are injured or specially affected by or are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change, as well as peoples and individuals of the present and future generations.

After hearing all the written and oral proceedings from all the entitled UN member-states (98), a handful of institutions, and organizations representing various stakeholders including the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC), the ICJ is expected to deliver its advisory opinion in early 2025.

Even though the court’s advisory opinions are not legally binding, as the principal judicial body of the UN, the ICJ’s assessment will provide authoritative guidance on the nature and scope of the state’s obligations in respect to climate change under international law.

It will provide a clear legal benchmark – including with regard to the rights of future generations – that will feed into national and regional court cases and the UN climate negotiations.

The landmark legal hearing at The Hague, reports Climate Home’s Isabella Kaminski, has seen top climate diplomats and advocates strongly criticize wealthy countries that are big emitters of planet-heating gases using the Paris Agreement and other existing treaties on climate change to avoid additional pressure to step up their action to tackle global warming.

Powerful fossil-fuel-producing countries including the US and Russia are resisting what they regard as an attempt to force them to do more to rein in emissions and provide reparations to those suffering because of their carbon pollution.