2024: Year the world faced the sad impacts of climate change

As the world ushers in a new year, 2024 will be remembered with trepidation as the year that the distressing impacts of climate change were acutely felt everywhere across the globe.

Devastating floods destroyed lives and property in Kenya and Brazil. Nearly 300 people died and more than 160 went missing due to Kenya’s unusually heavy rains in March-May 2024.

Over 50,000 Kenyan households were displaced after a series of flash floods closed schools, interrupted healthcare services and destroyed thousands of acres of crops.

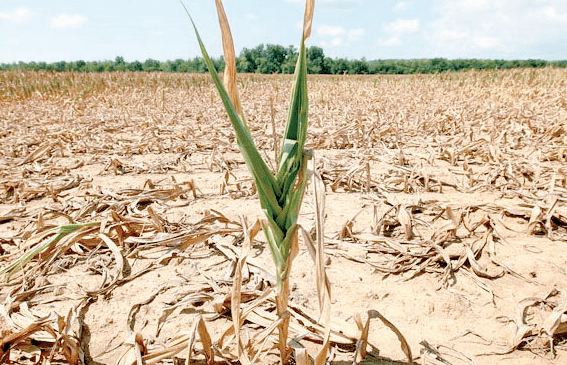

The year before that had been plagued by drought and many farmers watched helplessly as their crops withered and their animals died.

It was nature’s cruel twist of double jeopardy.

Beyond the African continent and the vast Sahel region that was also devastated by drought, across the Atlantic record wildfires scorched South America and extreme heat gripped cities across the United States.

“The top 10 hottest years on record have happened in the last 10 years, including 2024. This is climate breakdown in real-time. In 2025, countries must put the world on a safer path by dramatically slashing emissions and supporting the transition to a renewable future,” United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in his New Year message.

Flaming distress

In a review of the top stories of 2024, World Resources Institute (WRI) experts provided analysis that helped people understand pressing challenges, identify evidence-based solutions and inspire global ambition in efforts to tackle the impacts of climate change

“The list of our stories includes a virtual history of carbon emissions, ground-breaking analyses on water-stressed foods and extreme heat, a global action-tracker and so much more. It was an important year for people, nature and climate,” said WRI editorial director Sarah Parsons.

2024 witnessed an onslaught of climate disasters, from deadly floods in Kenya and Brazil to record wildfires across South America. WRI experts have explained why these events are getting worse and how people are building resilience in unexpected ways.

The latest data on forest fires confirms what we’ve long feared: Forest fires are becoming more widespread and damaging at least twice as much tree cover today as they did two decades ago.

Using data from researchers at the University of Maryland, recently updated to cover the years 2001 to 2023, the experts calculated that the area scorched by forest fires increased by about 5.4 per cent per year over that time period. Forest fires now result in nearly 6 million more hectares of tree cover loss per year than they did in 2001 – an area roughly the size of Croatia.

Fire is also making up a larger share of global tree cover loss compared to other drivers like mining and forestry. While fires only accounted for about 20 per cent of all tree cover loss in 2001, they now account for roughly 33 per cent.

The increase in fire activity has been starkly visible in recent years. Record-setting Forest fires are becoming the norm, with 2020, 2021 and 2023 marking the fourth, third and first worst years of global forest fires, respectively.

Nearly 12 million hectares – an area roughly the size of Nicaragua – burned in 2023, topping the previous record by about 24 per cent. Extreme wildfires in Canada accounted for about two-thirds of the fire drive tree cover loss last year and more than one-quarter (27 per cent) of all tree cover loss globally.

Climate change is one of the major drivers behind increasing fire activity. Extreme heatwaves are already five times more likely today than they were 150 years ago and are expected to become even more frequent as the planet continues to warm. Hotter temperatures dry out the landscape and help create the perfect environment for larger, more frequent fires.

When forests burn, they release carbon that is stored in the trunks, branches and leaves of trees, as well as carbon stored underground in the soil. As forest fires become larger and happen more often, they emit more carbon, further exacerbating climate change and contributing to more fires as part of a “fire-climate feedback loop”. This feedback loop, combined with the expansion of human activities into forested areas, is driving much of the increase in fire activity we see today. As climate-fuelled forest fires burn, larger areas, they will affect more people and impact the global economy.

WRI experts also looked at the scenario of what 3 degrees Celsius of global warming would look like. What would happen if the world stays on course for nearly 3 degrees Celsius of temperature rise this century? They modelled future heatwaves and other climate risks.

The world recently experienced a 13-month streak of record-breaking global temperatures. And as blistering heatwaves punish communities across several continents, 2024 is on track to be the hottest year on record.

Global average temperatures are now perilously close to exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, a threshold scientists warn will bring increasingly dangerous droughts, wildfires, and other impacts of climate change.

Researchers project nearly 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 F) of temperature rise by 2100 without significant action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

This means that nearly 600 million people will be exposed to flooding from rising seas, food production will drop by as much as half and habitats will suffer disastrous levels of loss. But what will 3 degrees of warming vs, 1.5 degrees look like in specific places – like Bengaluru, Johannesburg, Rio de Janeiro or the city you live in?

New data from WRI finds that in most cities, the difference between 3 degrees and 1.5 degrees of warming is sizable. The experts analysed potential climate hazards for nearly 1,000 of the world’s largest cities, currently home to 2.1 billion people or 26 per cent of the global population, using estimates based on downscaled global climate models.

At 3 degrees of warming, any city could face month-long heat waves, skyrocketing energy demand for air conditioning, as well as a shifting risk for insect-borne diseases – sometimes simultaneously. People in low-income countries are likely to be hardest hit.

These findings hold immense consequences for people’s lives and livelihoods, as well as for cities’ economies, infrastructure and public health systems. The implications are especially important as cities are home to 4.4 billion people globally, or more than half the world’s population, and which will grow rapidly over the next two decades.

By 2050, as another 2.5 billion people move to urban areas, two-thirds of humanity will live in cities, with over 90 per cent of that growth being in Africa and Asia.

Some hope

However, it was not all doom and gloom. During the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) held in Baku, Azerbaijan early last month, nations forged a new climate finance deal that, while insufficient, can help build resilience in the country’s most vulnerable to climate change.

Earlier in September in New York, world leaders adopted a ground-breaking pact to transform global governance.

The Pact, designed to turbo-charge implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), was the culmination of an inclusive, years-long process to adapt international cooperation to the realities of today and the challenges of tomorrow.

“We cannot create a future fit for our grandchildren with a system built by our grandparents,” the UN chief succinctly put it.

The Pact for the Future includes a Global Digital Compact and a Declaration on Future Generations.

It is the most detailed agreement ever at the United Nations on the need for reform of the international financial architecture so that it better represents and serves developing countries.

The pact covers a broad range of issues including peace and security, sustainable development, climate change, digital cooperation, human rights, gender, youth and future generations and the transformation of global governance.

World leaders committed to accelerating measures to address the challenge of climate change, including through delivering more finance to help countries adapt to climate change and invest in renewable energy.

Size of Croatia.

Fire is also making up a larger share of global tree cover loss compared to other drivers like mining and forestry. While fires only accounted for about 20 percent of all tree cover loss in 2001, they now account for roughly 33 percent.

The increase in fire activity has been starkly visible in recent years. Record-setting forest fires are becoming the norm, with 2020, 2021 and 2023 marking the fourth, third and first worst years of global forest fires, respectively.

Nearly 12 million hectares – an area roughly the size of Nicaragua – burned in 2023, topping the previous record by about 24 percent. Extreme wildfires in Canada accounted for about two-thirds (65%) of the fire drive tree cover loss last year and more than one-quarter (27%) of all tree cover loss globally.