Treasury, counties must budget for project maintenance

Driving around Kenya, one is accosted, in every county, by the large number of public institutions that are going to seed because the national government and counties have failed to budget for repairs and maintenance, particularly of buildings and installations.

A case in point is the Kipchoge Keino Stadium in Uasin Gishu, which is not only abandoned with the work less than half done but which has probably earned its place as Kenya’s top monument of shame. Uasin Gishu prides itself as “the home of champions”. Its athletes have made Kenya proud by their sterling achievements on the global stage.

Yet, the county has no stadium, or well-maintained open field, track or any other facility that current or up-and-coming athletes can train at. Despite this, Kenyans keep expecting that the country will continue dominating in athletics even in the absence of either public or private funding for sports talent development infrastructure.

Over the years, the National Treasury has prioritised funding of new mega projects that have impressive figures like Sh300 billion. Ironically, the projects that have the potential to impact Kenyans directly, such as the repair and maintenance of school buildings, are perennially ignored. The result is all too evident. A school like Kapsabet Boys in Nandi County continues to perform well in national examinations because the management invests in ensuring that the institution looks good from within and without. No wonder, it attracts hundreds of students each year.

The same, however, cannot be said of some public schools in the neighbouring Elgeyo Marakwet County. Here, the dilapidation of once high-profile schools that produced political and business leaders of note is evident, highlighting the need for a rethink of budgeting processes at both levels of government.

As much as it is important to build new roads, railways and other public installations, it is equally important — if not urgent — to address the systematic decay of past public investments, particularly schools, hospitals, sports facilities and roads. Budgeting ought to move away from spending money on fashionable big-ticket projects when what was built in the past is allowed to die when it still has a public service to offer.

And this does not only affect rural counties. Urban areas like Nairobi, Nakuru and Mombasa are also replete with public institutions in dire need of a facelift because they still offer services that are in high demand, including public parks, estate amenities like access roads and regular services like garbage collection. In towns like Nakuru, garbage collection was a regular service in the 80s and 90s. The trucks were clean and run a scheduled programme. Although a city now, Nakuru has regressed from its heyday as a municipality.

The same goes for Nairobi. In the past, it ran a scheduled bus service and water was available all year round. Today, public transport is dead, the privately run sector is a study in chaos and residents have to stay up nights waiting to harvest water on the increasingly rare occasions that taps are not dry. Public spaces like Uhuru and Central Parks and the Kenya National Theatre remain closed and boarded up behind mabati walls, yet little or no work is going on behind the veil. As a result, the children of Nairobi are increasingly starved of recreational spaces. Indeed, we have effectively privatised recreation in the city. Is this the city we want to bequeath our future generations? Are we proud of the regression that we have been experiencing as a country when cities like Singapore, which borrowed our urban development model, have become global banking hubs and have mapped their development plan for the next thirty years when we are stuck in the doldrums?

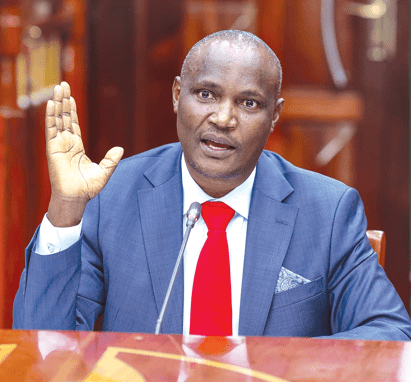

My argument is that there needs to be better coordination in the way public agencies allocate funding to both new and existing projects. The obsession with only new ones that gobble up large amounts of money — and are sometimes not even completed or done to satisfactory standards — ought to change. Is this an agenda that the new Treasury CS John Mbadi is willing to consider?

— The writer is the Editor-in-Chief of The Nairobi Law Monthly and Nairobi Business Monthly-