Tackling humanity’s Big Five inter-linked global calamities

Experts have cautioned that the only way to effectively address the five interconnected issues linked to global environmental, social and economic crises – biodiversity loss, water and food insecurity, health risks and climate change, is to tackle them collectively.

These interconnected issues interact, cascade and compound each other in ways that make separate efforts to address them ineffective and counterproductive, scientists have told 147 government representatives attending the ongoing historic eleventh session of the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in Windhoek, Namibia.

It is the first-ever meeting on the African continent bringing together the world’s leading scientific experts on biodiversity. IPBES is an independent intergovernmental body comprising governments and many NGOs established in 2012, which provides policymakers with objective scientific assessments and knowledge regarding the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems.

Experts affiliated to IPBES apply scientific evidence on the contributions biodiversity and ecosystems make to people as well as the tools and methods to protect and sustainably use these vital natural assets.

Yesterday (Tuesday) in Windhoek, IPBES launched a landmark new report, ‘The Assessment Report on the Linkages Among Biodiversity, Water, Food and Health’.

Known as the Nexus Report, it offers decision-makers around the world the most ambitious scientific assessment ever undertaken of these complex interconnections.

The product of three years of work by 165 leading international experts from 57 countries across all regions of the world, it finds that existing actions to address these challenges fail to tackle the complexity of interlinked problems and result in inconsistent governance.

The report also explores more than five dozen (60) specific response options to maximise co-benefits across the five ‘nexus elements’ of biodiversity, water, food, health and climate change.

“We have to move decisions and expectations beyond single issue silos to better manage, govern and improve the impact of actions in one nexus element on other elements,” said Prof Paula Harrison, who together with Prof Pamela McElwee, was the report’s co-chair.

She gave the example of the health challenge of schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, a parasitic disease that can cause life-long ill-health and which affects more than 200 million people worldwide.

“Treated only as a health challenge, usually through medication, the problem often recurs as people are re-infected. An innovative project in rural Senegal took a different approach– reducing water pollution and removing invasive water plants to reduce the habitat of snails that host the parasitic worms that carry the disease, resulting in 32 per cent reduction in infections in children, improved access to freshwater and new revenue for the local communities,” said Prof McElwee, adding that ‘Nexus approaches’ offer policies and actions that are more coherent and coordinated in bringing transformative change needed to meet development and sustainability goals.

Socio-economic drivers

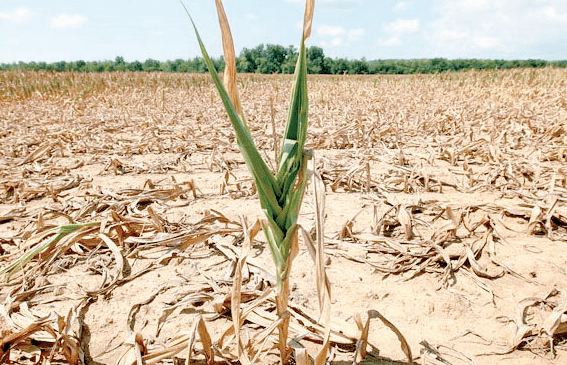

IPBES’s new report states that biodiversity – the richness and variety of all life on Earth – is declining at every level from global to local, and across every region. These ongoing declines in nature, largely as a result of human activity, including climate change, have direct and dire impacts on food security and nutrition, water quality and availability, health and wellbeing, resilience to climate change and almost all of nature’s other contributions to people.

The new report builds on previous IPBES reports, in particular the 2022 Values Assessment Report and the 2019 Global Assessment Report, which identified the most important direct drivers of biodiversity loss including land and sea-use change, unsuitable exploitation, invasive alien species and pollution.

The Nexus Report underscores how indirect socioeconomic drivers, such as increasing waste, overconsumption and population growth, intensify the direct drivers – worsening impacts on all parts of the nexus. The majority of 12 assessed indicators across these indirect drivers such as GDP, population levels and overall food supply, have all increased or accelerated since 2002.

“Governments and other stakeholders’ efforts often fail to take into account indirect drivers and their impact on interactions between nexus elements because they remain fragmented, with many institutions working in isolation, often resulting in conflicting objectives, inefficiencies and negative incentives, leading to unintended consequences,” notes Prof Harrison.

The report highlights that more than half of global gross domestic product (GDP) or more than $50 trillion of annual economic activity around the world, is moderately to highly dependent on nature.

“It is estimated that the unaccounted-for-costs of current approaches to economic activity –reflecting impacts on biodiversity, water, health and climate change, including from food production – are at least $10-25 trillion per year,” says Prof McElwee.

Delayed action

The existence of such unaccounted-for costs, alongside direct public subsidies to economic activities that have negative impacts on biodiversity (approximately $1.7 trillion per year), enhances private financial incentives to invest in economic activities that cause direct damage to nature (approximately $5.3 trillion per year) in spite of growing evidence of biophysical risks to economic progress and financial stability.

Delaying the action needed to meet policy goals will also increase the costs of delivering it. Delayed action on biodiversity goals, for example, could as much as double costs.

Delayed action on climate change also adds at least $500 billion per year in additional costs for meeting policy targets.

Prof Harrison says that another key message from the report is that the increasingly negative effects of intertwined global crises have very unequal impacts, disproportionately affecting some more than others.

More than half of the world’s population is living in areas experiencing the highest impacts from declines in biodiversity, water availability and quality, increases in health risks and negative effects of climate change.

These burdens especially affect developing countries, including small island developing states, indigenous peoples and local communities, as well as those in vulnerable situations in higher-income countries.

Studies show that 41 per cent of people living in rural areas saw extremely strong declines in biodiversity between 2000 and 2010, 9 per cent in areas that have experienced very high health burdens and 5 per cent in areas with high levels of malnutrition.

Efforts such as research and innovation, education and environmental regulations have been partially successful in improving trends across nexus elements, but the report finds these are unlikely to succeed without addressing interlinkages more fully and tackling indirect drivers like trade and consumption.

Decision-making that is more inclusive, with a particular focus on equity, can help ensure those most affected are included in solutions, in addition to larger economic and financial reforms.

The report’s authors conclude that future scenarios exist that have positive outcomes for people and nature by providing co-benefits across the nexus elements.

“The future scenarios with the widest nexus benefits are those with actions that focus on sustainable production and consumption in combination with conserving and restoring ecosystems, reducing pollution, and mitigating and adapting to climate change.”