Hunt for $1.3tr climate finance on, amid headwinds

More than 2,000 development finance professionals recently met in Cape Town, South Africa, for the Finance in Common (FiC) Summit, with two things on their minds – the dismantling of US foreign aid, and climate finance.

Other than drastic cuts to foreign aid and the disbandment of US’s 64-year-old development aid agency USAid established by President John F. Kennedy, experts also pondered on the new Donald Trump administration’s raft of unsettling decisions.

“In his first six weeks in office, it became clear that Trump was determined to undo not just Joe Biden’s environmental legacy, but an entire generation’s worth of action on climate change,” wrote Elizabeth Kolbert in Yale Environment’s E360 newsletter.

The Trump administration announced it is withdrawing from the Paris Agreement that seeks to limit global warming mainly caused by fossil fuels, froze the Inflation Reduction Act grants, stopped issuing permits for offshore wind development, and declared an energy “emergency” to boost fossil fuel production.

“The White House appears to be preparing to go after the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) “endangerment finding”, which undergirds EPA regulations on greenhouse emissions, while cutting EPA spending by 65 per cent,” said Kolbert.

FiC is the global network of all public development banks (PDBs), which aims to align financial flow on the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Agenda 2030 and the Agreement for climate change.

New target

Trump’s financial freeze on global climate action plans disrupted long-term demands by developing nations for the developed countries to give them $1.3 trillion a year in climate finance by 2030 to cope with the heavy burden of global warming caused by big emitters from wealthy nations, including the US.

Acrimonious discussions during the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (COP29) in Baku, Azerbaijan ended with disgruntled developing nations grudgingly accepting the $300 billion a year in climate finance deal.

Nations at the climate summit set a new goal, committing to deliver at least US$300 billion annually for developing countries’ climate action by 2035. Developed countries agreed to take the lead in fulfilling this effort.

The development finance meeting in Cape Town must have weighed in on the economic and geopolitical headwinds following Trump’s decision to dismantle foreign aid and cripple US funding for climate action.

Development finance as it has existed for decades, with a focus on official development assistance, is dead, experts told Devex senior reporter Adva Saldinger.

Not just because of the Trump administration’s actions but also the cuts to foreign aid across Europe, including in the UK early this month.

The aid cuts gave a sense of urgency to the summit and the broader FiC Summit (FiCS) effort, said French Development Agency CEO and chair of FiCS, Rémy Rioux. The question at FiCS was what will emerge to replace it, and what role the world’s public development banks will play in the new reality.

There are some 536 PDBs across 155 countries, which represent about 10 per cent of total annual global investment, according to FIC. The goal of FiCS has been to organise those institutions, share knowledge, and work together to achieve climate and development objectives.

At the summit, there was greater demand for collaboration and coordination with the larger ecosystem of public finance institutions, including multilateral development banks. This meant higher-level participation by MDBs at this summit. Inter-American Development Bank President Ilan Goldfajn, World Bank Senior Managing Director Axel van Trotsenburg and Jin Liqun, president of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which was one of the co-hosts, spoke at the summit.

“Finance in Common Summit was not just about seizing a pivotal opportunity, but also inviting all stakeholders to be part of shaping the future of development finance and position Africa at the centre of global financial discussions,” said Development Bank of South Africa chief executive Boitumelo Mosako.

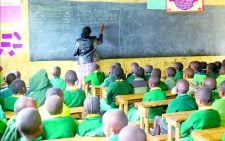

There is need to strengthen partnerships across institutions and come up with data-driven, pragmatic solutions to fund sectors including infrastructure, energy, water, transportation, healthcare, education and affordable housing, she said.

Africa has been at the forefront in seeking climate finance, encompassing public and private financial resources, to support actions addressing climate change including mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Developing nations have largely avoided discussing finance, international cooperation and adaptation to climate impacts in the context of a just transition from fossil fuels, a position further hardened by the stance Trump has adopted.

When nations set the new climate finance goal of US$300 billion annually by 2035 in Baku, the goal, known as the new collective quantified goal (NCQG), it included a much larger target, Natalia Alayza and Gaia Larsen wrote for the World Resources Institute (WRI).

The NCQG calls on all actors to work toward mobilising $1.3 trillion in international climate finance over the same timeframe; much closer to the amount developing countries truly need.

The finance, alongside their domestic finance, is essential for developing countries to adopt low-carbon technologies, protect themselves from climate threats and unleash green development.

Down payment

“Stronger action in the developing world is needed to halt climate change and invest in sustainable growth globally. It’s about building a safer and more prosperous future for everyone,” Alayza and Larsen said, delving into what it will take to reach the US$300 billion threshold – and what moving beyond it, toward $1.3 trillion, could look like.

Is the new climate finance goal enough? The NCQG’s $300 billion target is the largest climate finance commitment countries have ever agreed to and represents an important down payment for climate action. Meeting it will be a critical milestone. But finance cannot stop there.

The High-Level Expert Group on Climate Change estimates developing countries (excluding China) need to spend US$2.7 trillion by 2030 to meet climate and nature-related goals, with $1.4 trillion coming from domestic sources and $1.3 trillion from abroad

So, $1.3 trillion is therefore a more accurate reflection of developing countries’ needs by 2035, and so the more important target. But of course, it is the much larger hill to climb. Important, too, is understanding how and where the funds will flow,” they write.

And is the $300 billion achievable? Yes, they agree, noting that though current political headwinds make it more difficult, achieving the goal remains possible. In 2022, the latest data available, developed countries delivered around $116 billion to developing countries for climate action.

This exceeded the previous climate finance goal of $100 billion annually, which the NCQG replaces. Against this background, $300 billion by 2035 is very much in reach. How this money is raised, though, could have implications for the type of finance made available and who can access it most easily.

The money would come from bilateral finance, multilateral finance, such as from multilateral banks and multilateral climate funds, and private funds mobilised by public funds. Alternative sources may also include international taxes or rechannelled IMF special drawing rights.

Ultimately, moving beyond US$300 billion, toward $1.3 trillion, will require much more private investment in climate action than has been seen to date, in addition to increases from the mentioned sources.