Majestic Mt Elgon, unique home of abundance, risks

Mount Elgon, the majestic 24 million-year-old extinct volcano mountain that straddles the Kenya-Uganda border, is home to an ecosystem that hosts a vast, rich agricultural area and a unique wildlife reserve.

The volcano’s higher reaches are protected as a national park, but its lower slopes sustain the livelihoods of more than 500,000 people.

Mt Elgon is located within Mt Elgon sub-county in Bungoma County in Kenya, and within Mbale, Sironko, Bududa and Kapchorwa districts in Uganda.

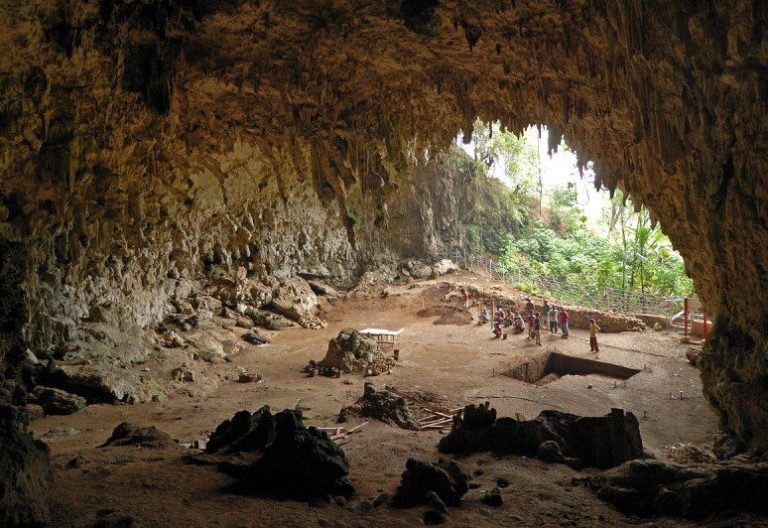

Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) describes Mt Elgon National Park as “a unique wildlife reserve high in the mist-wreathed hills of a volcanic giant where visitors can explore the forest, see elephant caves and enjoy hiking on Africa’s eighth highest mountain.

This sanctuary of biodiversity in the vast expanse of the majestic mountain is one of Kenya’s best-kept secrets and a globally acclaimed natural tourist attraction.”

Renowned English broadcaster and natural historian Sir David Frederick Attenborough, the foremost global environmental conservation campaigner, a voice of wisdom on wildlife conservation, climate change and the impact of humans on the planet, inspired a study on the cave elephants of Mt Elgon.

But that’s the story for another day.

The focus is turned on the threat of climate change to Mt Elgon’s rich agricultural heritage. As growing populations strip its slopes and heavy rain intensifies, this sanctuary has become increasingly vulnerable to landslides.

Landslide losses

Responding to this threat, farmers on the Ugandan side of the mountain are planting native trees and changing the crops they plant to build resilience against future disasters, according to two journalists, Ugandan Alex Wandeba and Briton Freddie Clayton, writing in the latest edition of Yale Environment 360.

The deadly landslides are forcing an agricultural reckoning for farmers like Francis Gidegi, 46, who says the native trees he plants like jackfruit, avocado and Cordia Africana bind the soil, and the perennial crops like robusta coffee that stabilise the land alongside short-term crops like onions and maize.

Gidegi has dug trenches and contours to slow water flow and prevent erosion on his three-acre farm that benefits from fertile soils, cool mountain air, and steady rains.

It is not the quickest and easiest way to produce crops, but these are necessary efforts to safeguard his family of 15 in a landscape that offers both abundance and risks.

In November 2024, heavy rainfall triggered a series of landslides that tore through villages in the mountains of Bulambuli district, including Gidegi’s Kamwanyi village, where torrents of mud and rock swept everything from their path, displacing hundreds, destroying roads, and leaving behind deep crevasses where homes once stood.

At least 28 people died.

Landslides have long plagued the mountain, but they’ve grown more frequent and destructive in the last two decades as a burgeoning population alters the landscape and heavy rains, which saturate soil and loose rocks, intensify, write Wandeba and Clayton.

Hillsides once anchored by forests have been cleared for timber and housing, and fast-growing crops like maize and beans have left the soil degraded and unstable.

A 2025 study found that the Mt Elgon biosphere reserve’s transition zone, where human activity is permitted, has experienced a 76.7 per cent decline in forest cover.

On the Kenyan side, around harvest time, one marvels at the lush maize farms laden with maturing cobs and Kenya Seed Company Ltd plantations that make Trans Nzoia County the grain basket of Kenya, producing nearly a quarter of the total yield of the national staple.

Haulage trucks line up to load sacks of maize spread out to dry in the sun as clouds gather in the sky after a respite in unexpected rains during the harvest season, a reminder of the impact of climate change on the environment and the growing threat of human-wildlife conflict between the local farming community and the national park

Up the hill past farms to the winding, untamed wilderness and secluded splendour fissured by valleys and cascading streams, lies a unique natural sanctuary. The 169 square-kilometre Mt Elgon National Park in Trans Nzoia County is part of the Mt Elgon ecosystem.

Back in Uganda, experts warn that landslides in the country’s mountains are occurring more often and are deadlier, and farming these slopes becomes increasingly precarious.

But rather than abandon their homes and livelihoods, many local farmers are urgently turning to new methods to build resilience against future disasters.

These practices aim not only to reduce the risk of destructive landslides, but also to restore the soil before creeping degradation strips its ability to grow food. As Gidegi says, “Adapting is better than evacuating.”

Restorative tilling

In 2017, a local cooperative called MEACCE began teaching Mt Elgon farmers agroforestry techniques, a land-management system in which trees are managed together with agricultural crops and animals.

When well-designed, agroforestry increases productivity, reduces soil erosion, improves water conservation, and supports food security and livelihoods.

It is recognised globally for its role in climate adaptation, carbon storage, and biodiversity conservation.

Gidegi was aware of MEACCE’s methods but continued to rely on farming practices such as mono-cropping that cause erosion and deplete soil fertility.

The devastation of November 2024 marked a turning point.

That month, he and his family were among hundreds of people resettled to a flat, crowded area at the foot of Mt Elgon.

The hot weather and unfamiliar soil were a stark contrast to the rich, highland his family had cultivated for generations.

In April, he returned to Kamwanyi to start over again. But this time, his farming focused on healing the land, not harming it.

Gidegi began by planting a mixture of perennial crops and indigenous trees and digging trenches to divert stormwater.

“Before, we were cutting down trees, using chemicals, and burning bush,” he says. “But now we have stopped that”.

Following a spate of landslides, farmers like Gidegi across Mt Elgon are transforming their farms with support from a growing network of initiatives backed by cultural institutions, NGOs and the United Nations.

Thousands of residents have been trained in agroforestry techniques that improve soil health and water retention; millions of native tree seedlings have been planted.

Agroforestry is more labour-intensive than traditional farming methods and demands patience for slower-growing perennial crops, like coffee, and for native, deep-rooted trees.

Agroforestry sees profitable returns after three to eight years, while traditional annual cropping systems do the same within one to two years.

Fears exist that while NGOs and individual projects can make a meaningful difference, their impact can be short-lived if funding ends and farmers slip back into old practices.

The World Bank has warned that climate change and heavier rainfall could escalate the risk of landslides in Uganda’s mountain regions.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also projects that East Africa will see more frequent and intense rainfall as global temperatures rise.

Despite the risks of living on Mt Elgon, hundreds of thousands of people remain here, often because they have few alternatives.

“The place you were born is the place you prefer,” Gidegi says. “If we continue to work like this, we are going to benefit. We shall not face the same problems again”.