Urban refugees narrate their battle with mental health issues

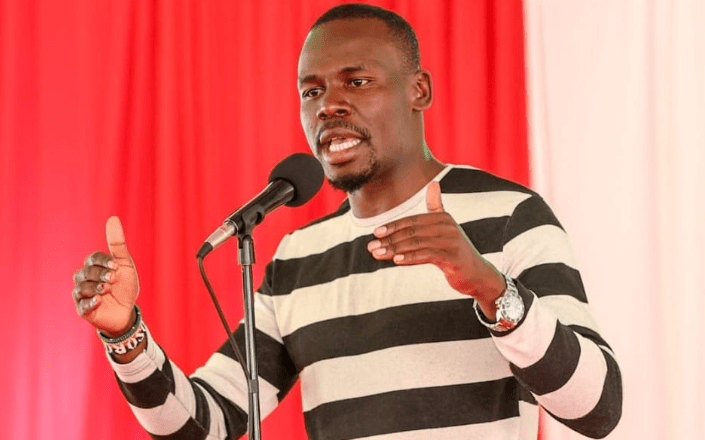

“There is comfort that comes in knowing where home is, and who home is,” Camilla the Poet says.

Those words, spoken at a community dialogue with around 70 refugees in Kawangware, Nairobi County, hit home for the congregation, most of whom sought refuge from Burundi, Rwanda, Congo, Somalia, and South Sudan when the war broke out in their different countries.

The dialogues, which have been ongoing for the last few months, are a lifeline to most of the refugees, most of whom are faced with mental health challenges on a day-to-day basis following their experiences during the wars in their countries. Most have never sought professional help.

Willie Twani, who has chaired the more than 4,400 refugees living in Kawangware for the last five years, narrated how many have ended up self-medicating with alcohol, sex and drugs as a coping mechanism for their mental trauma.

Anxiety and depression

“It is made worse by the fact that some Kenyans manipulate the labour laws to oppress the refugees, and do not even care that the kind of work they do is menial jobs. Our greatest advantage is that the lawmakers often come to their rescue. For instance, a few weeks ago, a policeman arrested a man who had refused to pay a Burundian refugee after selling him coffee and mandazis. The client had refused to pay claiming the vendor was not Kenyan and should go back to their ‘home’. The man was fined Sh10,000. This was just one of the examples where security agencies came to protect us as refugees,” he adds.

Twani says their minds are always a battlefield.

“Anxiety and depression are common here. This is worsened by the lack of jobs, including manual ones and the pay discrimination that arises once one starts working in certain places. Most of the time, they are paid half the salary and when they complain words, such as “go back to your home,” or “Kenyans can do this better,” are thrown at their faces,” he adds.

Twani narrates how a certain security company refused to pay some of the foreign employers for three months because they were refugees.

“It took the intervention of the area chief and local administration to force them to pay. The worst bit in the community is discriminated against even for expressing their issues,” he adds.

Racheal Nambaje, a community health worker who migrated from Congo points out that refugees have different and unique challenges, but each handles them differently.

“It is hard for them to open up to host communities, especially since many have not undergone such traumatic experiences and do not know how to handle them. Refuges also don’t understand the host community in the spaces they are in. They are ignorant of basic things due to non-communication with the people around them and hence are not aware that some documents are not supposed to be paid for. It is this mistrust that triggers mental instability, especially since they start asking questions, such as if they have been discriminated against due to their refugee status or due to the lack of job opportunities in the country,” she cites.

Past traumatising events

Alice Kwenda, a counselling psychologist, points out stigma surrounding the refugees, coupled with the fact that referral pathways are quite unknown, makes it hard for them to seek counselling services.

“It is the questioning of their self-worth that makes most of them shun getting help. Many are also traumatised by events of their past that they are unwilling to even come out of the cocoon they are in. The message preached should be that there is help available no matter the status you are currently in,” she advises.

Loise Giteru, who counsels refugees, advised refugees to work in structures when it comes to seeking counselling services and also in order to get job opportunities.

“Table banking groups, Community-based organisations and Nyumba Kumi officials’ meetings are good opportunities for peer debriefing and more concrete discussions around mental health,” she added.

Normalise therapy

She pointed out issues, such as secondary burnout (vicarious trauma) as common among them, advising them to normalise therapy as well as map out who is giving the services in the area.

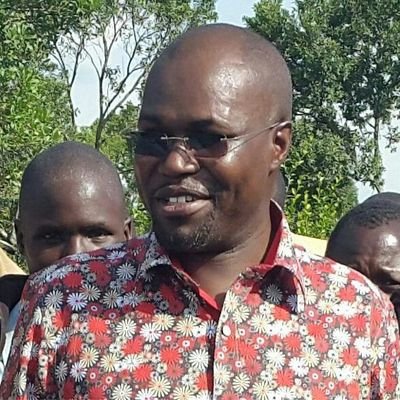

George Ogako, Satellite Sublocation assistant chief laments that most refugees do not take any initiative to empower themselves seriously for fear of being humiliated.

He emphasised that government offices are accessible and open to everyone and should report anything to the chief as a civil matter. If they cannot handle the cases, they refer them to relevant organisations, such as the rent tribunal.

“Personally, I get three updates daily on anything that is happening in this area. I also escalate issues that I cannot handle to higher authorities. However, refugees should never feel like they are not “citizens” enough that they cannot approach any government office and feel they are not attended to, they can report any government official to higher authorities,” he adds.

He advises them to take advantage of government provisions, such as the provision of methadol for those addicted to drugs.

“There are small steps we take to help protect them and they should walk with the assurance that the government is always on their side,” he adds.

Robin Omeka Nyakundi, the CEO of Anika Forums, an initiative that spearheads campaigns on urban refugees across the country, ventured into community dialogues as a means of giving them space to air out their grievances.

Attempted suicide

Through a partnership with GIZ and Mental 360, they target at least 500 refugees directly and more than 2,000 as a ripple effect of this training.

“We believe that all voices matter. With the influx of refugees, there has been a shooting up of cases of depression and attempted suicide and we seek to help prevent this. Understandably so because many left everything they possess including their families,” he adds.

Anika seeks to incorporate poetry and art therapy in the sessions too.

Recent data shows that approximately 81,000 or 16 per cent of the 500,000 registered refugees in Kenya live in urban areas. The actual number is likely higher as many refugees do not register with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the government. Due to the fact that urban refugees are dispersed and highly mobile, there is scarce data and limited understanding of their living conditions. This lack of understanding hinders efforts to enhance socioeconomic opportunities for them and the host communities. Addressing the risks and vulnerabilities faced by urban refugees and their hosts requires narrowing existing data gaps to inform policy options, including ones that enhance socioeconomic conditions and livelihoods opportunities.

UNHCR and the World Bank undertook the Kenya Urban Socioeconomic Survey 2020-2021 to close the data gap on urban refugees. Understanding their socioeconomic needs takes on added urgency with the potential closures of Dadaab and Kakuma refugee camps, the largest in Kenya, which may result in refugee influxes into urban settings. T refugees. According to the UNHCR demographic survey, 89 per cent of urban refugees reside in Nairobi while four per cent live in Nakuru and seven per cent in Mombasa. Mos had fled conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Somalia. Refugees’ counties of residence vary by country of origin. While Nairobi hosts a population from a wider variety of countries, refugees in Nakuru are mainly from South Sudan and those in Mombasa tend to be from Somalia.

The survey generated numerous practical implications for policymaking and response. While food insecurity is alarmingly high among refugees, their employment rates are also very low. “Short-term priorities focused on food security, access to water, sanitation and housing will alleviate severe living conditions for highly vulnerable groups. Medium-term priorities should expand livelihoods opportunities, strengthen employment and entrepreneurial skills, ease access to education, foster social cohesion, and ensure access to information on movement options,” the survey recommended.

It further called for collaborations between the private sector, governments, humanitarian, and development partners will be essential to enable the creation of job markets.

Additional reporting by Betty Muindi