Tense talks as finance, fossil fuels dominate conference

Climate politics this week oscillated between two European capitals, Bonn in Germany and London in the UK, amid tense talks on three critical issues that pit developing and developed nations – finance, adaptation and fossil fuels.

At the London Climate Action Week, Kenya’s climate envoy Ali Mohamed led the least developed countries (LDCs) in warning that without addressing “the centrepiece of climate change” – finance – “it is difficult to get any significant outcome at November’s United Nations climate summit (COP30) in Belém, Brazil.

Back in Bonn during the annual mid-year UN climate conference convened to prepare the groundwork for the summit in Brazil, which ended yesterday, the elephant in the room was still finance.

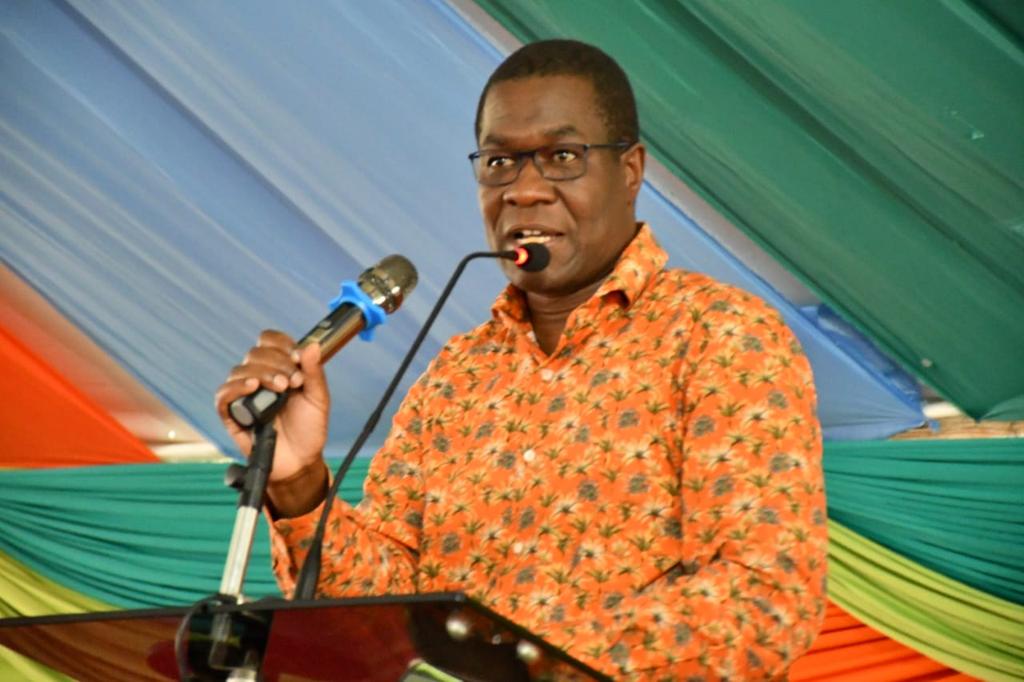

Stepping up their climate ambitions and throwing the gauntlet to wealthy, developed and oil-exporting nations, the developing countries called for adaptation finance to triple by 2030. The chairperson of the LDCs group, Evans Njewa, appealed for a new and more ambitious goal for adaptation finance.

Climate Action Network International’s Shreeshan Ventakesh said the “weak decision” on the new goal at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, where developed countries agreed to deliver $300 billion per year by 2035, “is leaving a mark and stopping a constructive, progressive decision from being made” in Bonn.

Climate experts say that although it seems like another lifetime, it is only 18 months ago that United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Executive Secretary Simon Stiell hailed “the beginning of the end” of the fossil fuel era.

At COP28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, all countries agreed to a set of collective actions – including transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, tripling renewables and stopping deforestation – in response to their failure to keep climate goals on track as evidenced by the 2023 Global Stocktake (GST).

The GST discussions focus on how the world’s governments should respond to being collectively off track to meet their goal to limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels adopted in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

But that breakthrough in Dubai is now “at risk” unless the delivery of those promises is speeded up urgently, Jennifer Morgan, an architect of that landmark COP28 deal and until recently Germany’s climate envoy, told London Climate Action Week.

How to do that?, posed the authoritative UK-based Climate Home News digital publication. One obvious place, it said, is the dedicated “dialogue on implementing the GST outcomes” at the UN climate talks.

“But discussions in that negotiating track broke down at COP29 in the face of concerted resistance by oil-exporting countries. And now, in Bonn, they appear to be heading in a similar direction with no shared understanding even on what the dialogue should cover and the purpose of this space”.

And in an ominous no-nonsense message posted on LinkedIn, Noura Hamladji, the deputy head of the UNFCCC secretariat, the UN body that organises the UN climate talks, and keeps work going throughout the year, warned: “THE WORLD IS ON FIRE. FUND THE FIRE DEPARTMENT”.

Hamladji was referring to negotiations on how much money governments should give the UNFCCC – the metaphorical fire-fighters – for 2026-2027 so that it can carry out its ever-growing list of activities governments have told it to do. The two options in the latest draft, according to Climate Home, are for 2026-2027 to be around the same as 2024-2025 – $74 million over the two years.

Or for a 24 per cent increase up to $92 million. A note from Stiell said that, without an increase, the sustainability of the UNFCCC process and of the secretariat would be jeopardised,

At a meeting on Tuesday, governments told the UNFCCC to draw up two budgets with around a 10 per cent increase and a 19 per cent increase, according to three sources in the room – a recommendation that will disappoint the UNCFCCC and those who rely on its work.

They said Saudi Arabia said they did not have a mandate to go above 10 per cent. And the UK, which wants 24 per cent, proposed 19 per cent as a compromise.

Without money to fulfill its functions, the UNFCCC would need to raise supplementary voluntary contributions from governments and other sources like philanthropies – such as Michael Bloomberg, who has stepped in to fill the financial hole left by the US government under President Donald Trump.

While in Bonn, countries remained deeply divided over how to implement the responses to the GST, COP30 host Brazil sought inspiration in London.

Developing countries, small island states and the Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) group of Latin American nations want to put the focus on “collective progress” towards meeting the GST goals, ideally by holding an annual ministerial summit and producing reports.

But others like the Like-Minded Developing Countries – which counts China and Saudi Arabia among its members – and India have pushed back, saying this forum should not become an assessment mechanism or set new targets, according to a summary of discussions published by the International Institute of Sustainable Development (IISD) Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

The pressure is on Brazil, which only a week ago pinned the implementation of the GST goals to the top of the action agenda for this year’s climate summit in Belém. “The time of finger pointing is gone,” said COP30 CEO Ana Toni, calling for “mature” debate on the energy transition. Shuttling between stuffy rooms in Bonn and glitzy events in London over the last week, she said it was in the UK capital that she saw “real life moving”/ “We haven’t been able yet to translate that real life to the negotiation rooms,” Toni told Climate Home. “The transition is inevitable. We need to capture that and bring it into politics”. How that will be reflected in the final outcome in Belém is still far from clear.

Meanwhile, calls to triple adaptation intensified in Bonn. At COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, four years ago, governments agreed to double finance for adapting to climate change to around $40 billion a year by 2025.

That goal ends this year, although it will not be known until 2027 if it has been met. But at a news conference in Bonn on Tuesday, the LDCs group chairperson, Njewa, called for a successor goal – tripling adaptation finance by 2030 on 2022 levels. “Adaptation is a lifeline,” he explained. Other developing countries are likely to back this.

Grupo Sur and the Like-Minded Developing countries have made the same call in different negotiating rooms, and Njewa said he was sure that the small island states group Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) would back it too.

“We are never going to say no to adaptation finance,” Thibyan Ibrahim, finance negotiator for AOSIS, told Climate Home in Bonn. But he noted that even tripling “does little to close the adaptation finance gap”.

The UN estimates that developing countries need $160 billion-340 billion a year by 2030, whereas tripling on 2022 levels would bring in just under $100 billion.