Loggers, charcoal dealers destroy Nyakweri forest

An expansive community forest that is home to more than 80 families of elephants in Transmara is on the verge of depletion as people clear it for human habitation.

Nyakweri Forest that neighbours Masai Mara Game Reserve is now a charcoal-burning zone, as loggers troop the area to get a slice of it while it lasts.

Natural resource was until five years ago a closed canopy forest.

It is the biggest supplier of charcoal to Western Kenya, Nairobi and Mombasa.

Hardwood like the White Podo being harvested are supplied to the local market and also exported to United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, locals say.

The hands of both the national government and Narok county are tied because it is a community forest, giving locals an upper hand on how it is supposed to be utilised.

Conservationists and officials of Community Forest Associations (CFAs) are disturbed by the developments, since residents are pushing it to the brink of depletion.

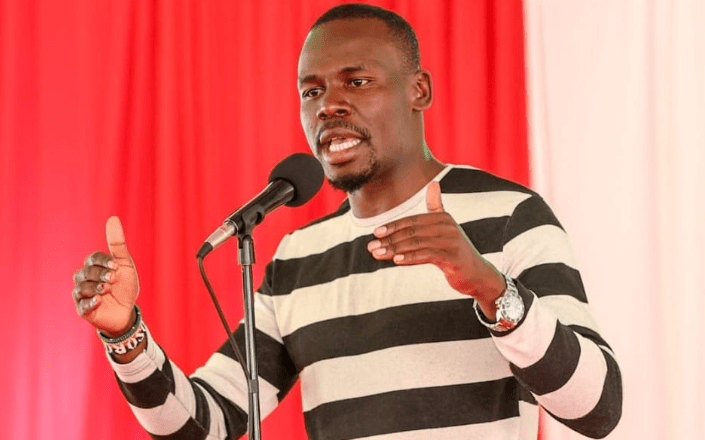

“We raised concern about it when the destruction started years ago but except for some interventions by both the local county and national governments, nothing tangible was put in place to stem it,” says Peter Naikada, chairman of Dupoto Community Forest Association.

Naikada says currently, there is little that can be done to stop people from clearing the forest because they are doing so to open up spaces for habitation and other developments like farming and cattle rearing.

“People want to clear it as fast as they can to settle down and exploit it to the maximum. After all, they say it is their ancestral place,” he says.

Security teams

Naikada adds that Kenya Forest Service (KFS) tried to intervene in a bid to end the destruction but could not achieve much because it is a community forest where people own parcels of land.

He further argues that if it was a trust land under the county government like Maasai Mau where about 10,000 families who had settled in it were kicked out in 2019, the destruction and other activities could have been stopped and settlers evicted.

His CFA, he says, was desperate and is lobbying to have the destruction of areas where the elephant families live and breed and also their migratory corridors stopped.

“We plan to partner with other like-minded CFAs, wildlife and environmental conservation groups to lobby the government and donors to buy out those who are clearing the elephant habitats and their migratory corridors to and from Masai Mara,” he says.

But for it to succeed, he says, locals have to be sensitised and to be brought on board, adding that even if it means buying their land at prices way above the market prices, it should be done for the sake of tourism and for livelihoods of thousands of people who depend on the forest.

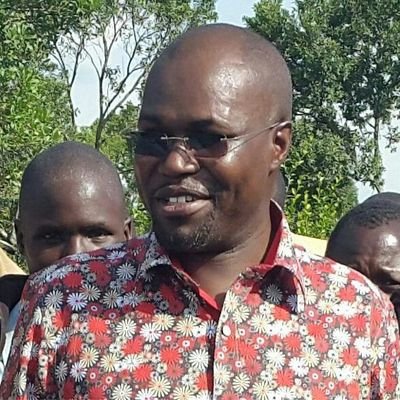

Nick Murero, chairman of Narok Environment Forum says Mogor River, which passes through the forest, and other sources of clean water are bearing the brunt of the destruction, claiming that the river and other water bodies are contaminated.

“Massive soil erosion because of the ongoing clearing and farming activities on the upper part are making humans, livestock and wildlife animals water consumption dangerous.

Analysis shows that phosphate and human waste have already found their way into the water bodies,” he says.

Effects of the destruction, he says, are being felt in Serengeti and Ngorongoro in Tanzania, the larger Western Kenya and parts of south Rift Valley.

“There is no need for hundreds of people to disrupt lives of millions of people and their economy, including our neighbours in Tanzania.

When this problem started, the government was reluctant to act but now that is affecting many people and their livelihoods, legal action must be taken to save it,” says Murero.