Living with disability but marching on unbowed

In 1984, American civil rights activist Jesse Louis Jackson made a memorable clincher; a shout out to the rights of the disabled “I’d rather have Franklin D Roosevelt (FDR) in a wheelchair than Ronald Reagan on a horse.”

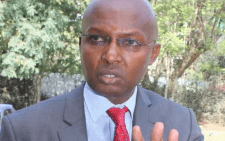

These are the words that Abdinasir Khalif Mohamed, a person living with disability (PLWD) and a social rights activist borrows while trying to bridge the gap between the disabled and the general public.

Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the US (1933-1945) won a record four presidential elections, always with a landslide.

“He is said to have done a lot during the Great Depression, the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialised world, that lasted from 1929 to 1939,” Khalif, a lover of history explains.

Like Roosevelt, Khalif’s disability is a result of poliomyelitis.

Khalif was born in a remote village in Wajir. The effects of missing polio vaccines would eventually be a permanent reminder of his current state of disability—deformity in his lower limbs. Moving around has been a challenge since he was three years old.

Death that inspired

From crawling from one place to another, being carried in a wheelbarrow by his siblings to sometimes hiking on donkey to Benane Primary School and later to County Council Mixed Secondary School in Wajir, Khalif has seen it all.

He laments the stigma that’s associated with PLWDs. “They call me Abei (Jiss), a negative connotation among the Somali meaning, physically challenged,” reflects Khalif, who has been championing for the rights of PLWDs for over two decades.

“Disabled young people have same needs for sex education, healthcare and opportunities to socialise and discover themselves as their abled peers,” says Khalif, who never had an opportunity to have such kind of discussion with his parents because it was perceived embarrassing.

A public relations graduate from the University of Thames in the UK, Khalif is married and a father of seven—five boys and two girls.

“I have witnessed friends who have failed to get families, either because of discrimination, fear of rejection, among others. I am happy to have a loving family,” he asserts.

He is a younger brother to the late Labour minister Ahmed Mohammed Khalif, who perished in the 2003 aircraft crash—three weeks into President Kibaki’s administration.

The death, he says, devastated the family and the region in general. The older Khalif was not only the family breadwinner, but also a uniting factor in the northern region.

“He was a man of the people with utmost humility. He loved peace and unity, he wanted good for everyone, I am not surprised that a school is named after him, Hon Khalif Girls Secondary School, nicknamed ‘Alliance in the desert’, the first girls school in Wajir West constituency.

My brother was a Muslim scholar recognised for championing democratisation.

To date, he is fondly remembered for his contribution to religion, education and development.

That is why when he died, the community decided to honour him by building community Madrasa bearing his name,” recalls Khalif.

The passion of his late brother is what led Khalif to start the Northern Kenya disability Forum, which advocates for the rights of the disabled.

“The law stipulates that all children with disabilities have a right to free and compulsory education.

That is a huge positive. However, the law fails to provide reasonable accommodations in education, which amount to disability discrimination,” he argues.

Act only on paper

While the Persons with Disabilities Act, 2003 was seen as a game changer, Khalif is worried not much has been achieved for the disabled community.

“The comprehensive law was meant to cover rights, rehabilitation and equal opportunities for people with disabilities.

The act also saw the formation of the National Council of Persons with Disabilities as a statutory organ to oversee the welfare of persons with disabilities. But to a larger extent, the law is just on paper.

For instance the law requires that both the public and private sector employers reserve five per cent of jobs to disabled person, sadly it doesn’t happen,” says the activist.

“Treatment with dignity and respect, access to educational institutions and facilities, reasonable access to all places, public transport and information and even to use sign language, braille or other appropriate means of communication, are immediate matters that need to be addressed.

“Just take a look at our public transport. Nobody cares about people of my kind. It is quite sad. That is why I say the Disability Act is only on paper.

Having lived in London for over seven years while studying, Khalif cannot help but draw comparison on how the two nations are living worlds apart when advocating for disabled people.

“The government takes care of her people equally, the disabled have monthly stipends from the government, and basically all their needs are taken care of,” he notes.

Khalif lives for the day when this country will consider people for who they are, not based on their tribe, region of birth and most importantly, physical appearance.

“I’m not ashamed of my situation. I want to be example to many—polio can be avoided. Children need to be vaccinated against the virus,” he says.