On EAC integration, citizens lead the leaders

What a week it has been for Kenya-Tanzania relations. The two neighbours risk weakening the bonds that hold them together due to Gen Z-related activities. Tanzania’s founding father, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, believed in the common bond that united the region to the extent that his country delayed self-rule unless Kenya and Uganda were on board.

Years to come would not be kind to this affection. With Kenya’s President Jomo Kenyatta ageing and Uganda’s Milton Obote deposed by Idi Amin, relations among the three countries were strained.

Kenya, increasingly influenced by presidential advisers who looked to the West, contrasted with Nyerere, who clung to socialist ideals; the common estates held by the nations were divided among the three countries.

Years later, Tanzania would spearhead the effort to oust Idi Amin from Kampala. Amin, the soldier whose military career began in Kenya before he returned to Uganda and expelled Obote, had stained his country with blood. Nyerere could not take it.

While the founding fathers – Nyerere, Kenyatta, and Obote – were in power, East Africans enjoyed free movement across the borders to live and work. Even today, many reflect on those good old days with nostalgia – the trips across Lake Victoria, the shared airline and railway lines, and so forth.

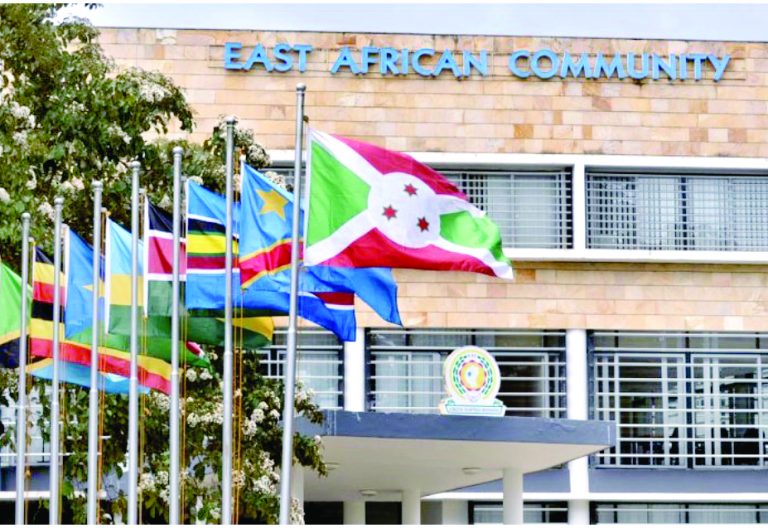

It would be years before the new regimes in Kampala, Dodoma and Nairobi began to explore opportunities for reunification. However, it has never been the same. The journey to creating the East African Community (EAC) has been slow, progressing one step at a time, yet marked by increasing suspicion, particularly among the leaders.

However, if the recent past is any indication, the slow pace of the movement towards East African integration may be more apparent at the official level than at the grassroots level.

The steps towards integrating the EAC with its headquarters in Arusha included a customs union, a common market, a monetary union, and a political federation. The first was expected to be completed in 2005, while the second was set to be finalised five years later. However, all these are significantly behind schedule.

The EAC remains at the common market stage, which promotes the free movement of people, services, goods, capital, and labour. The appearance of an ordinary passport is in place, along with flags and a community anthem, among other elements. However, Arusha is lagging behind.

Not so with the people. Many areas indicate that individuals are progressing with integration, and nothing exemplifies this more than the arts. Regional artists enjoy popularity across the border.

This awareness has taken a significant step forward. Perhaps it was the arrest in Nairobi of Kizza Besigye that prompted Kenyan lawyers to cross the border to monitor the case.

Now, Tanzanian opposition leader Tundu Lissu of the CHADEMA party has been charged with treason. Kenyans empathise with his plight – previously shot and left for dead, he sought refuge in Europe before imprisonment, his life mirroring Raila Odinga’s experience. While politicians engage with bureaucracies in Arusha, citizens are advancing political association independently. Despite Tanzania’s deporting of Kenyan activists dampening federation hopes, perhaps, just perhaps, the seed is germinating.

The writer is Dean of Daystar University’s School of Communication