IEBC: New dawn or familiar sideshows?

Kenya’s democratic journey, though relatively young compared to mature democracies, has been repeatedly tested at the ballot box.

Though elections have become defining moments—episodes where hope for renewal is so often overshadowed by suspicion, confusion, and claims of betrayal, it has stood the test of time. It is within this environment that the reconstitution of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) must be understood.

On June 10, 2025, President William Ruto appointed a new chairperson and six commissioners signalling a turning point.

Yet, as a historian and political observer, I find it difficult to share in the celebratory tone adopted by sections of the political class.

Kenya has been here before—too many times. In fact—and while the names may change, the institutional rot often remains intact. The reconstitution of the IEBC is not the solution in itself. It is the beginning of a long, difficult, and painstaking process of repairing broken trust.

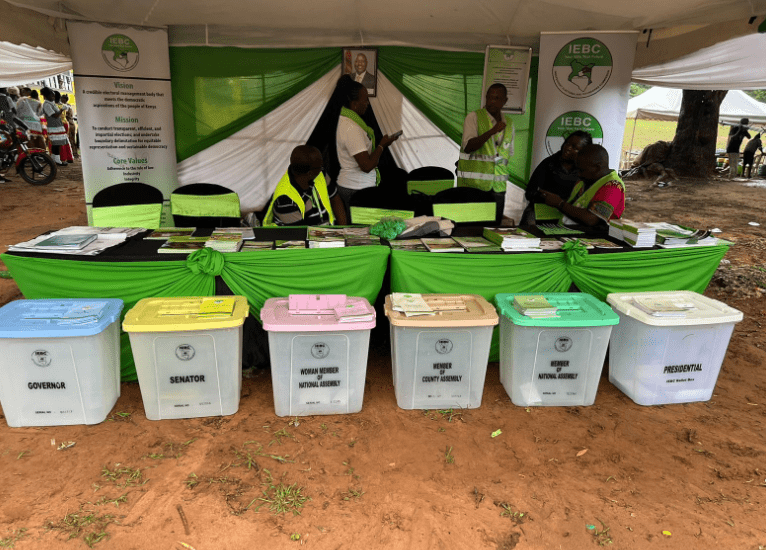

The 2010 Constitution birthed IEBC—a reform charter necessitated by the ghosts of the 2007–2008 post-election violence. It was envisioned as an impartial, well-resourced body that could deliver credible elections and facilitate national cohesion.

However, over the last decade, IEBC has staggered from one crisis to another. The 2013 election, though largely peaceful, left many Kenyans feeling uneasy due to opaque result transmission processes and a judiciary that, for some, prioritised legal formalism over substantive justice.

The 2017 polls exposed the commission further—its presidential results were annulled by the Supreme Court for irregularities and illegalities, an unprecedented ruling in African electoral history.

In 2022, the chaos was internal: a divided commission where four commissioners openly disowned the final results, leading to a crisis of confidence so severe that the IEBC effectively ground to a halt.

That dysfunctionality is what the new team must now undo.

Erastus Ethekon as the new Chairperson of the IEBC, and commissioners Ann Njeri Nderitu, Moses Alutalala Mukhwana, Mary Karen Sorobit, Hassan Noor Hassan, Francis Odhiambo Aduol, and Fahima Araphat Abdallah have a huge task ahead of them.

This group comes from diverse professional and regional backgrounds, ticking the boxes of representation and technical experience. Their gazettement followed the recommendations of a selection panel and subsequent vetting by the National Assembly.

However, the process was not without controversy.

A conservatory court order temporarily halted their swearing-in, citing procedural impropriety and inadequate public participation. Though the court later lifted the order, the legal contest served as a reminder of how delicate—and contested—the terrain of electoral administration remains in Kenya.

But beyond legality lies legitimacy. The question now is not whether the commissioners were lawfully appointed. It is whether they can restore public confidence in a commission that, over the years, has earned more criticism than commendation.

If this new team hopes to be different, it must begin by confronting the institutional baggage it inherits.

This includes poor communication, opaque procurement practices, mismanaged voter registers, and the ever-present spectre of political interference.

These are not abstract concerns—they are the very factors that have made the IEBC synonymous with distrust in the public psyche.

As someone who has closely followed Kenya’s electoral trajectory, I believe that the problem is no longer technical capacity. Kenya has run elections. It has deployed technology. It has held training workshops and civic education drives.

The challenge, as always, is political will—both within the commission and among the political elite.

The new commissioners must actively reject the temptation to align themselves with any camp, whether overtly or through quiet complicity.

Independence, after all, is not declared. It is practised. And in this age of hyper-partisanship, practising institutional independence will require courage bordering on defiance.

Captured institution?

The IEBC’s internal governance must also be reimagined. What happened in 2022 was not just an embarrassment—it was a constitutional calamity.

A commission whose members contradict each other publicly on matters as sensitive as presidential results cannot be trusted to oversee a local by-election, let alone a national vote.

This time, the commission must enforce internal discipline and unity. Let disagreements be ironed out within boardrooms, not aired at press briefings.

Commissioners must remember that their power lies not in individual prominence but in collective legitimacy.

Transparency is the oxygen of credibility. The IEBC must open up its processes to public scrutiny.

Procurement of electoral materials, recruitment of polling clerks, training programs, and audit of the voter register must all be transparent and accountable. The commission should not shy away from third-party monitoring or civil society engagement.

In fact, it must institutionalise such engagement if it hopes to insulate itself from political capture.

Kenyans are tired of learning about failed KIEMS kits and untraceable Form 34Bs only after the damage is done.

Proactive disclosure is no longer optional—it is imperative.

And then there is the issue of technology. While digital tools have become indispensable to modern elections, they have also been used—deliberately or through negligence—to obscure accountability.

From server delays to unexplained downtimes, IEBC’s digital infrastructure has been more a source of controversy than confidence.

The new team must invest not only in better systems but also in public understanding of those systems. Let the voter know how the system works.

Let political parties have access to monitoring frameworks and, most importantly, let there be contingency plans when technology fails because fail it often does.

Yet, even as IEBC reforms itself internally, it must push for broader legislative and policy reforms. Parliament must be persuaded to revisit electoral laws and clarify timelines, tighten controls around party nominations, and review campaign finance frameworks. Reform cannot be outsourced.

The commission must lead it. It must also resume the long-delayed boundaries review process, conduct a comprehensive audit of the voter register, and work closely with the Judiciary and Office of the Registrar of Political Parties to clean up Kenya’s increasingly fragmented and toxic electoral environment.

But perhaps the greatest challenge facing the new IEBC is psychological, not legal. It must convince a sceptical nation that it is not another “political project.”

It must shake off the label of a captured institution and position itself as a credible, competent, and neutral arbiter. That will not happen overnight. It will require consistent action, professional conduct, and open communication. Trust, once broken, is rebuilt in drops and lost in buckets.

I remain cautiously hopeful. I believe Kenya cannot afford another botched election. We cannot keep cycling from optimism to outrage every five years. We must break the cycle. The new IEBC has a chance to do that.

Mr Ethekon and his team must understand that this is not just a job. It is a national calling. Their actions—or inaction—will either anchor Kenya’s democracy or push it further toward democratic fatigue and disillusionment.

Let them rise to the moment, not for political praise or historical applause, but because the republic deserves nothing less.

Kenya’s future, fragile as it may seem, still hinges on credible elections. That credibility begins and ends with the IEBC. This reconstitution must mark the end of political convenience and the beginning of principled leadership.

Anything less would be a betrayal of the millions who line up, patiently and in hope, every election cycle—believing that their vote still matters.

The writer is a History Lecturer & UASU Chapter Trustee, Alupe University-Kenya.