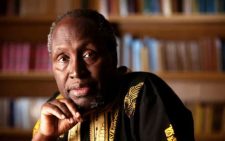

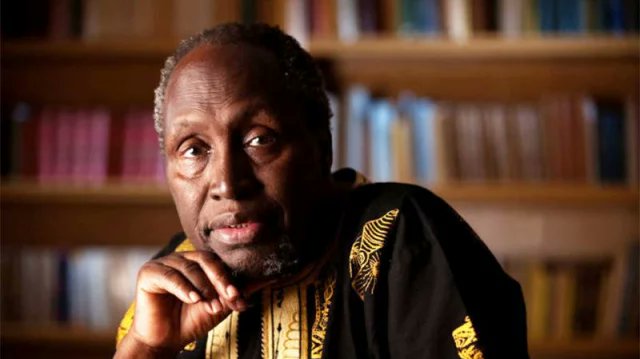

Cremation wrong: Kenyans deserved to bury Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Japan has built a long tradition through which an outstanding artist and cultural icon, such as Ngugi wa Thiong’o, can be declared a “Ningen Kokuho” or “living national treasure.”

Such an artist is then funded by the government for life, assured of a pension and facilitated to mentor disciples and apprentices who can preserve that art form or take it forward.

Had Ngugi been Japanese, he would most probably have been honoured as a living national treasure.

He was not Japanese, unfortunately, and Kenya, his motherland, failed to honour him when he was alive.

This failing notwithstanding, the fact remains that Ngugi deserved to be buried in Kenya and a shrine built in his honour in his home village in Kamirithu, Limuru.

That way, his soul would have remained rooted in Kenyan soil and those who valued him in life, as well as those who esteemed his work as a literary artiste, would have had a place to pay homage to his enduring contribution to Kenya’s cultural and intellectual superstructure, Marxist though he may have been.

In my view, the decision regarding whether Ngugi was to be cremated – and cremated abroad for that matter – was not a luxury that the government ought to have afforded him or his family.

After all, Ngugi was not his own man in the sense that other private citizens are.

If anything, he was an indelible part of this country’s historical, cultural and intellectual heritage and the people of Kenya, and I dare say the State, owned him more than he or his family did.

As such, the choice was never his – or his family’s – to make in the first place and the fact that he was cremated abroad, in my view, borders on criminality.

This probably explains why it was done in haste and utmost secrecy.

Under different circumstances (because now it is too late to turn back the hands of time), the government ought to have secured custody of his remains the moment news filtered in that he had died in the US.

From that point on, the State would have organised his interment in his motherland and at public expense.

According to Japanese tradition, a person declared a “national treasure” cannot be buried outside that country because he or she is designated as “a holder of important intangible cultural property.”

This is a tradition that we in Kenya ought to embrace, given that culture is a significant marker of our national identity and ethos.

The tragedy is that we lose a significant part of that identity whenever we allow our icons to be buried or cremated willy-nilly in any of the four corners of the wind, even if that was their dying wish.

The public deserves closure whenever such a person dies, and it is regrettable that Kenyans have been denied that catharsis in Ngugi’s case.

Holding vigils and symposia in honour of Ngugi’s spirit is all good, but highly transient since we do not have a culture of preserving records of such events.

And at any rate, we will hold them today, but tomorrow we will move on with our lives as if nothing happened.

But what will happen to lovers of literature who desire, in, say, ten years, to visit Ngugi’s birthplace or burial place?

What happens to all the possibilities of starting a museum, cultural centre, and shrine in the soil where his roots are anchored?

The writer is the Editor-in-Chief of The Nairobi Law Monthly and Nairobi Business Monthly