Nobel Peace Prize would be best posthumous befitting send-off for Ngugi wa Thiong’o

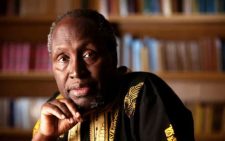

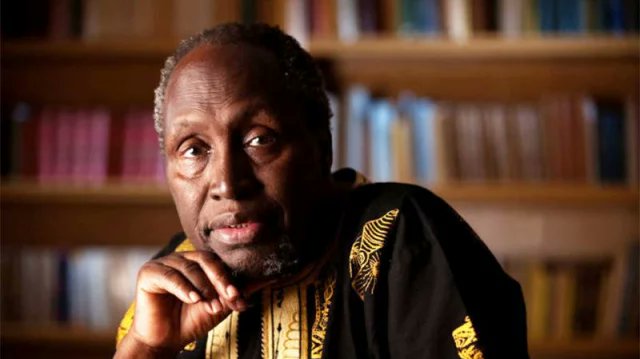

The death of Ngugi wa Thiong’o on May 28, 2025, at the age of 87, marks the end of a towering literary, philosophical, and political voice from Africa.

As tributes pour in from around the globe, the question that lingers—quietly yet powerfully—is this: Should Ngugi wa Thiong’o now be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize posthumously?

Traditionally, the Nobel Peace Prize is awarded to individuals or institutions who have made significant contributions to peace, diplomacy, or reconciliation efforts.

Unlike the Nobel Prize in Literature, which celebrates artistic merit, the Peace Prize often honours direct political or humanitarian action.

Still, exceptions have been made for those whose contributions to peace came through ideas, speech, and influence—areas where Ngugi’s legacy towers.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o was more than a writer. He was a cultural warrior, a political prisoner, an educator, and an uncompromising advocate for the liberation of the African mind.

His weapon of choice was the word. Through novels, plays, essays, and public speeches, he challenged colonialism, neocolonialism, and internal repression with a defiant clarity that inspired millions.

In the face of state censorship, imprisonment, and exile, he never wavered from his commitment to justice and the dignity of the African people.

In doing so, Ngugi contributed not only to literature but also to the architecture of moral peace.

Native Gikuyu language

Born in colonial Kenya in 1938, Ngugi witnessed firsthand the brutality of imperial rule.

This experience shaped his early works, such as Weep Not, Child and The River Between, which explored the psychological and societal damage inflicted by colonialism.

But it was in the 1970s that he truly transformed from a novelist into a revolutionary cultural figure.

He abandoned English in favour of his native Gikuyu language, arguing that true decolonisation must begin with language.

His 1980 novel, Devil on the Cross, was written on toilet paper while he was held in prison without trial—a punishment for organising a play that criticised government corruption and inequality.

Ngugi’s insistence on linguistic and cultural self-determination was not merely academic.

He believed that peace could only be achieved when people were free to express themselves in their own languages, think with their own metaphors, and define their own futures.

In this sense, he was fighting for the internal peace of individuals and communities long fractured by colonial subjugation.

His call was for mental liberation—what he termed “decolonising the mind”—which, while nonviolent, was deeply political and revolutionary.

His ideas reverberated far beyond Kenya. Across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and among diasporic communities, Ngugi inspired writers, students, and activists to reevaluate the power dynamics embedded in language, education, and culture.

His call for African languages to occupy central positions in literature, academia, and governance was a call for equitable global dialogue.

He sought a world where no culture was diminished, no tongue silenced, and no people made to feel inferior for the circumstances of their history.

And what is peace, if not the presence of justice, dignity, and mutual respect?

Though Ngugi never took up arms, his struggle was no less fierce. His pen exposed oppression challenged systems of control, and gave voice to the voiceless.

He was imprisoned for his beliefs, exiled for his activism, and overlooked by major Western literary institutions for decades—likely because his truth was too uncomfortable for those invested in global power hierarchies.

Yet he remained unbowed, returning to Kenya later in life and continuing to write and speak out against injustice wherever it reared its head.

That the Nobel Prize in Literature eluded him is one of the great oversights of the Swedish Academy.

But now, in death, there is an opportunity for the Nobel Committee to right a larger historical wrong.

Kamomonti teaches English and Literature in Gatundu North Sub-County