Democracy doesn’t offer desired stability

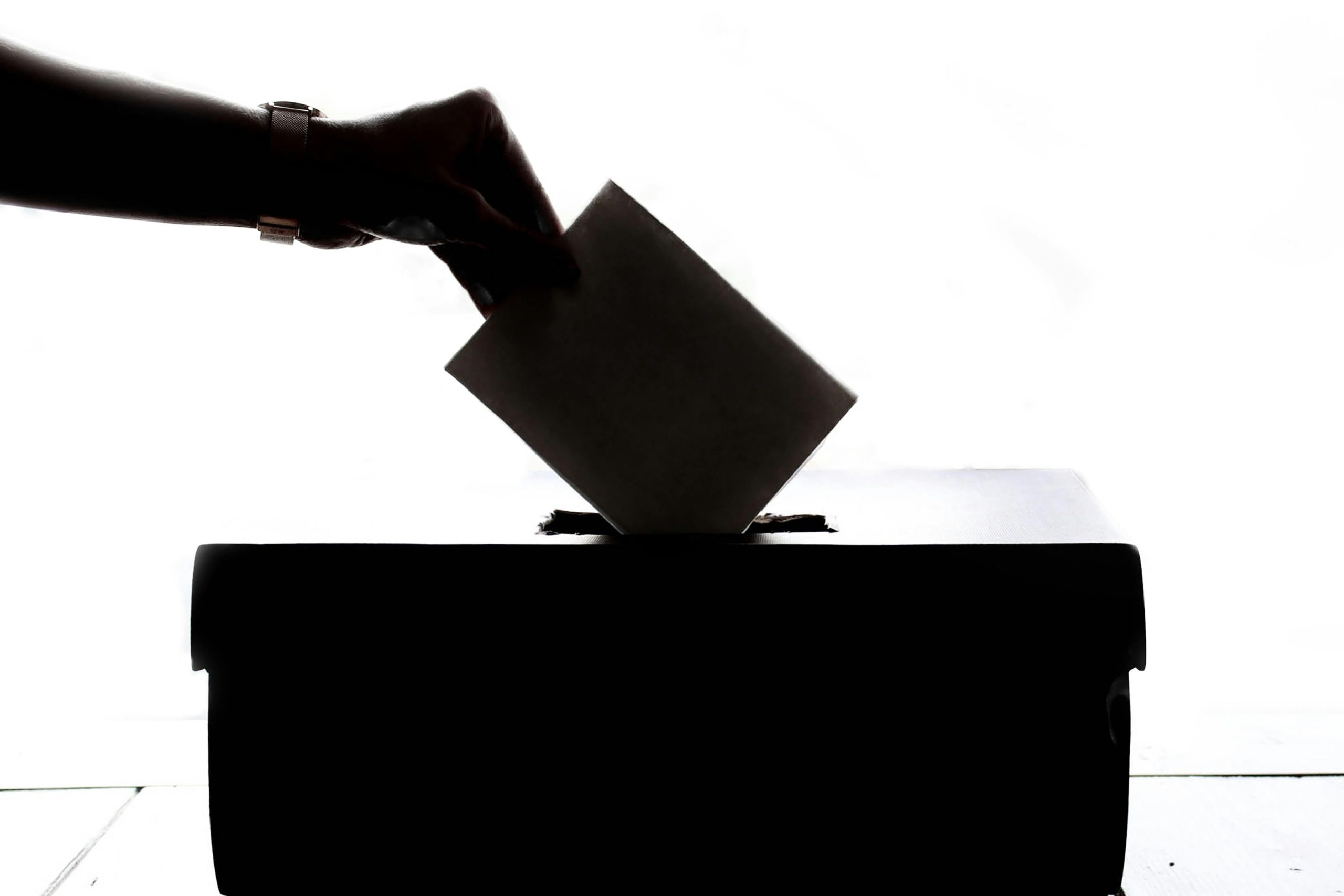

Why is democracy such a mess? For now, consider what is happening in South Korea. President Yoon Suk Yeol, who has been in office for only three years, faces impeachment for declaring martial law in the country.

That decision came after a period of seeming political instability, and yet democracy was supposed to be the cure for such instability.

The fate of Yoon was almost predictable, for it seems the fate of most South Korean leaders is not to retire in peace.

Sample this: President Park Geun-hye before him ended up in jail; Lee Myung-bak was also jailed for 15 years; Roh Moo-hyun ended his own life after leaving office; Chun Doo-hwan was jailed; Park Chung-hee, father of Park Geun-hye, was assassinated, and so on.

Yet, while South Korea’s politics seem to be tottering as if the nation is on the brink of collapse, the economy continues to blossom.

Seoul is the fourth-largest economy in Asia after China, Japan, and India and the 12th-strongest globally. It is a major exporter of electronic goods to China and the world, and its cars – KIA and Hyundai, among others – dot the world’s roads.

However, it is not just in South Korea where democracy appears to be messy. Look at what elections in the world’s largest economy and only superpower, the United States, have led to.

Joe Biden, a seeming consensus builder with comparatively moderate social credentials, will be succeeded by Donald Trump, who dreams of being a dictator, even if for one day.

The world’s third-largest economy, Japan, is also struggling with democracy.

For a while now, France has struggled to have a stable government. After the prime minister suffered a no-confidence vote, the budget for the next financial year hangs in the balance. President Emmanuel Macron will find it difficult to appoint a successor.

But France will have to live with its political mess, as elections are not due until 2025 at the earliest.

Germany is not breathing any easier. The government is barely holding, with elections to be held by February 2025.

The same is true for many other countries, including in Africa. Kenya has successfully held elections every five years since independence but the nation appears unsure of itself now.

In South Africa, the continent’s largest economy, the president also faces a potential impeachment motion in parliament. Namibia’s disputed election brought its first female president to power.

Yet, while these democracies appear to be struggling politically, they are still strong economies relative to their seemingly politically stable counterparts. Scholars of Chinese studies consider Beijing a democracy if regular elections are the measure of democracy.

Countries led by strong leaders, even if their economies are not among the top in the world, provide stability and predictability.

While you may not know what 2027 will bring to Kenya, you can rest assured that Yoweri Kaguta Museveni will be president of Uganda and that the economic policies will remain the same.

Kampala’s views regarding LGBTQ+ will remain constant. That assurance will also apply to neighbouring Rwanda and faraway Russia, among others.

Political scientists must thus explain the allure of democracy more closely. Nothing matters more to a citizen than the sense of security and predictability that policies that contribute to the national welfare will not be held hostage by political interests in the name of democracy.

Since coming to power two and a half years ago through a democratic process hailed by the US through its diplomatic office in Nairobi, Kenya has hardly offered anything resembling predictability.

The players in the democratic space, the opposition party, are probably no clearer on their stand than the government.

Today, Kenya witnesses the rise of organised religion as a sign of providing a competitive voice in the political space. This is the same as the years of former president Daniel Arap Moi. Democracy has to offer more promise and stability to its people.

— The writer is the Dean of Daystar University’s School of Communication