Rise and fall of Moi’s powerful Constitutional Affairs minister

If Charles Mugane Njonjo was President Jomo Kenyatta’s powerful legal adviser and Attorney General, he wielded even more power as President Daniel arap Moi’s close and trusted Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister until an acrimonious political fallout.

Under the Kenyatta administration, Njonjo held the Sword of Damocles and later played kingmaker during the sunset days of the Founding Father.

Under Moi, Njonjo was regarded as the power behind the throne; he was one of the few Kenyans who tasted absolute power.

Njonjo served for 17 years as the first AG of post-independence Kenya from 1963 to 1980, and then for three more years as Justice and Constitutional Affairs minister.

During his colourful and often controversial career as AG and Cabinet minister, Njonjo often took rides in the limousines of the two Presidents and participated in the selection of ministers, ambassadors and other key members of government.

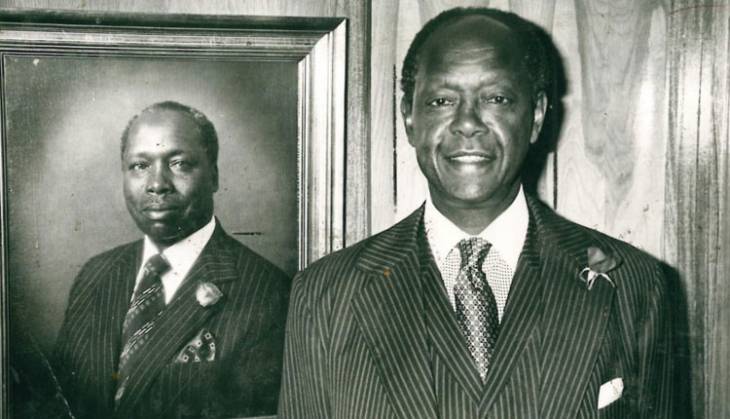

At the pinnacle of his momentous political career in 1983, the man nicknamed ‘the Duke of Kabeteshire’ due to his unusual English mannerisms was second only to Moi – despite not being vice-president.

However, his fall from power was swift and brutal after he was implicated in the 1982 coup attempt by elements of the Kenya Air Force.

Accusations that he was a “traitor” formed the basis of a protracted Judicial Commission of Inquiry leading to his ignominious exit from public service.

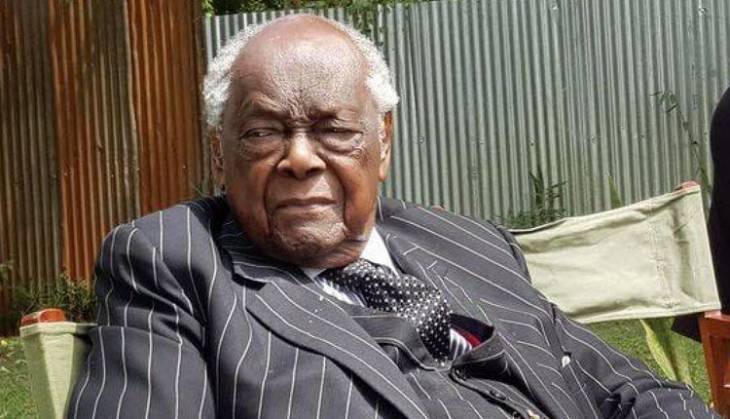

Until his death yesterday at the age of 101, Njonjo was the only surviving member of Kenya’s first Cabinet.

Alliance High

Born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth, the son of colonial Paramount Chief Josiah Njonjo, Charles Njonjo was born in Kibichiku, Kabete, in Kiambu District on January 23, 1920, in a prominent family of four brothers and four sisters.

The young Njonjo led a pampered life and was said to ride to the local Gwa Gateru Primary School in Lower Kabete on a horse accompanied by a servant.

His father was one of the foremost collaborators of the British in Kenya.

The school was associated with the heavily bearded Canon Leakey, the pastor in charge of the nearby Protestant church, now the Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK) Mother Church, Kabete.

Later, Njonjo joined the prestigious Alliance High School in nearby Kikuyu, sharing a class with Jeremiah Nyagah who would later become a colleague in the Cabinet.

For a boy used to the comforts of a colonial chief’s home, Alliance was quite tough.

“Students did not wear shoes and we showered with cold water. This is where I ate ugali for the first time,” he recalled.

In 1939, Njonjo joined King’s College, Budo, in neighbouring Uganda for a two-year pre-university course.

He was in the same class as Frederick Mutesa, who later became the Kabaka (King) of the Baganda.

After Budo, his father wanted him to go to the UK for further studies but this was not to be. Instead, he enrolled at Fort Hare University in South Africa for three years to study Administration, Sociology and South African Criminal Law in addition to Latin.

He described life in South Africa as “terrible” due to the apartheid system. “I would travel from Durban to Fort Hare and in the whole train there would be only one uncomfortable compartment for natives (blacks).

We even carried our own food as we were not allowed into the dining car. At the railway station, you could not cross the path of the whites and one had to go round and round to exit or enter the station,” he disclosed.

After completing his studies, Njonjo returned to Kenya for one month before flying to the United Kingdom to join Exeter University for a postgraduate course in Public Administration.

He completed his studies at Exeter in 1947 and proceeded to register at the London School of Economics until 1950. He thereafter studied law for four years before he was called to the Bar at Gray’s Inn.

“My father could not afford my college fees and I had to do manual work, including washing dishes, to see myself through college,” Njonjo explained regarding his prolonged stay in the UK.

He much preferred life in that country to his previous experience in South Africa.

On his return to Kenya from Britain in 1954 he was employed by the colonial government as a High Court Registrar serving in Mombasa. He was soon promoted to Registrar-General and moved to the Attorney General’s office as Senior Crown Counsel in 1955.

He served diligently as a colonial government lawyer during the troubled Emergency period, in the course of which the government committed atrocities against Kenyans including mass arrests, torture and detentions as well as arbitrary removal of families from their ancestral lands and herding them into “reserves” from where they provided slave labour for the rapidly proliferating white farms.

One year before independence, the diligent Njonjo was promoted to the powerful position of Deputy Public Prosecutor, a heartbeat away from the position of AG.

“When Mzee (Jomo Kenyatta) became Prime Minister, I was appointed Attorney General and when Kenya became a Republic in 1964, I became an ex-officio Member of Parliament and the Cabinet,” he explained.

During his 17-year service at Sheria House as AG, Njonjo occasionally shocked the nation by expressing views that were diametrically opposed to the country’s foreign policy or even that of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) – not to mention prevailing local sentiments.

For instance, he was widely known to be a proponent of continued white rule in apartheid South Africa, Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) and Mozambique; he wanted Kenya to maintain diplomatic ties with the pariah apartheid South African regime, to the chagrin of Kenya’s Foreign minister Munyua Waiyaki; he negotiated the Israeli military raid on Entebbe airport in Uganda to free Israeli hostages held by terrorist airplane hijackers; and he was strongly opposed to the existence of the tribal grouping known as the Gikuyu, Embu and Meru Association (GEMA) which he had registered in 1971 and thereafter sought to proscribe in 1976.

Njonjo had Kenyatta’s ear and was consulted often, making him a very powerful man in every sphere. So close a confidant of Kenyatta was the AG that he was credited with recommending Moi as Kenya’s third vice president after the resignation of Joseph Murumbi, a proposal Kenyatta gave favourable consideration.

Vice President Moi

“As we drove one day in the presidential limousine from some town in the Rift Valley after Murumbi had resigned as vice president, Mzee wondered loudly whom he would appoint to replace Murumbi.

Then Kenyatta asked me: ‘Who do you have’? To which I replied, ‘How about Moi’?” Njonjo recalled.

According to him, Kenyatta was so pleased with this proposal that he appointed Moi as VP the next day.

To his credit, Njonjo initiated many of the laws that transformed Kenya from a colony to a free and independent country, and established the many institutions that became the bedrock of democracy and good governance in Kenya under the 15-year leadership of Kenyatta.

Njonjo got married in 1972 at the age of 52. “I was married to my work,” he confessed. He further explained, “I loved my work as Attorney General of Kenya, worked odd hours that would have put a spouse off.

For a long time I did not entertain the idea of marriage. Outside the office, I had hobbies that I enjoyed thoroughly and I thought this was enough for me.”

But he was under pressure from every quarter. Kenyatta wondered for how long he would be advised by a bachelor.

Njonjo’s mother, Wairimu, wanted grandchildren too. Being a steadfast follower of the ACK, it was the church that eventually got him a wife.

In the early 1970s during church services at the All Saints Cathedral in Nairobi, the AG noticed a girl in the choir. Sometimes she would be seated in the same pew as him.

“I would look at her and think to myself, ‘Now, there is a nice girl’. My pastor also thought she was the right partner for me and would invite us and other faithful to his house for dinner,” Njonjo recalled.

Margaret Bryson was British and the pair gradually got to know one another well, eventually marrying in a colourful wedding on November 20, 1972. They were blessed with three children.

As AG and later as Cabinet minister, Njonjo was a stickler for the law, which was why he stood firm on the whole issue of the Kenyatta succession when he insisted that the country must follow the constitutional path.

The Constitution provided that in the event of the death or incapacity of the sitting President, the Vice President would take over for 90 days before fresh elections were held.

In 1976 when Mzee’s health started failing, therefore, the AG came out fighting in opposition to a potentially divisive and destructive campaign by a lobby group fronted by Kiambu politicians Njoroge Mungai and Njenga Karume, Nakuru kingpin Kihika Kimani, the ‘King of Meru’ Harvester Angaine and his Ukambani counterpart Paul Ngei and others.

They were determined to amend the Constitution to bar VP Moi from automatically succeeding Kenyatta upon his death.

The group’s “Change the Constitution” campaign reached a crescendo when it held a charged rally in Nakuru at which Ngei asked Kenyans to give him the reins of power for just three days, and declared openly that he would never relinquish the position.

Limousine ride

An ally of Moi, Njonjo rejected the group’s proposals in a heated debate in the National Assembly and accused them of imagining the death of the President which, he informed them, was treasonable.

“You do not change the Constitution by the roadside. I told the group to stop imagining the death of the President and instead take an amendment to Parliament if they had a genuine cause instead of playing the tribal card,” he recalled.

The group’s scheme was successfully thwarted by the combined force of Moi and his supporters who included Finance minister Mwai Kibaki along with Njonjo, who quite likely had personal motives of investing in their own political future.

When Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, and was succeeded by Moi, Njonjo retained his position as AG as he had anticipated, but with the added reputation of being a kingmaker and a defender of the Constitution and democracy.

The AG’s relationship with Moi, however, turned temporarily frosty a few weeks into the latter’s presidency when Njonjo was quoted by the media as allegedly saying that the Moi regime was nothing but “…a passing cloud”. The whole hullabaloo soon faded away and the damage quickly repaired.

As AG under Moi, Njonjo cultivated his relationship with the new Head of State, to such an extent that the two became inseparable; a team that was expanded to include the Minister for Internal Security, G.G. Kariuki.

The trio rode in the Presidential limousine as Moi criss-crossed the country consolidating his authority and introducing his Nyayo philosophy on meet the people tours, harambee fundraisers, inspection of development projects and attendance at church services.

When he hit 60, having put in 17 years of service as AG, Njonjo felt it was time to move on. In an orchestrated and well-choreographed move, he called a press conference to announce his resignation as AG and his intention to contest the Kikuyu parliamentary seat only a day after the incumbent MP resigned to allow Njonjo to vie for the seat.

Exactly as expected, Njonjo easily won the seat and transformed himself into a politician overnight.

As part of the orchestrated changes, he was appointed Cabinet minister in the specially-minted Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, a position he held until 1983.

The ministry strategically roped in the Judiciary and, as it was during his days as AG, Njonjo worked closely with the national security apparatus – making him the single most powerful person after the President.

Seven bearded sisters

In Parliament, where he was in his element owing to his superior grasp of the English language and access to classified information, Njonjo was admired and feared in equal measure.

Rightly or wrongly, he was associated with Moi’s excesses including the arrests and torture of perceived dissidents and detentions without trial.

His popularity suffered when he introduced Bills and Constitutional changes seen as oppressive, and others aimed at creating what came to be called an imperial presidency.

Owing to the perception that he was misadvising Moi to brutalise his opponents and to implement tough government policies, Njonjo met with stiff opposition from Parliament, especially from a group of seven young and highly intelligent MPs, namely Koigi wa Wamwere, Mashengu wa Mwachofi, James Orengo, Chelagat Mutai, Abuya Abuya, Onyango Midika and Lawrence Sifuna.

“Parliament was at times amusing and we had people who thought they could get away with anything.

But I challenged them head on. There was, for example, this group of seven radicals … and I referred to them jokingly as the ‘Seven Bearded Sisters’.

They were intelligent, but I could not allow them to use their intelligence to push everybody else about,” he commented regarding his engagement with the group.

Come the August 1, 1982, attempted coup by elements of the Kenya Air Force and Njonjo’s massive political edifice started to crumble.

After the putsch failed and as military elements were court-martialled and politicians taken to court, Moi decided to purge the ruling party, Kenya African National Union (Kanu) and the Cabinet of figures he believed wanted him out of power.

Chief among them was Njonjo and the equally powerful Internal Security Minister ‘GG’ Kariuki.

In yet another well-choreographed plan which included finger-pointing in Parliament against anti-Moi elements, real or imagined, Njonjo was eventually named ‘the Traitor’ by fellow Cabinet minister Elijah Mwangale.

What followed was a protracted Judicial Commission of Inquiry presided over by the eccentric Justice Cecil Miller of Jamaican descent.

In the end, the Inquiry concluded that Njonjo was guilty of abuse of office and that he had tried to take over power from Moi. He was forced to resign from government, effectively destroying his political career.

For many political observers, it was hard to imagine how Njonjo could gamble with and destroy his career spanning 22 years by trying to overthrow the man he fought so hard to establish in State House after Kenyatta’s death in 1978, the man on whose behalf he almost single-handedly managed the transition and for whom he gambled all, including risking estrangement from his Kikuyu community.

Njonjo insisted he had no intention of overthrowing Moi, saying the whole thing was hatched by people who thought he was too powerful and wanted him out of the power equation.

“They claimed that I had the support of America and Britain. This was not the case at all. These people were like wild dogs baying for the blood of a rabbit,” he said.

Njonjo had nothing but contempt for the Miller Commission. “During the Inquiry, I was not worried as I knew my conscience was clear and I was not guilty.

In any case, had I wanted to ensure Moi did not become President all I had to do was to join hands with the 1976 Change-the-Constitution group.

In the end, it left me with my head held high and nothing but contempt for the three judges who blatantly trampled on the law instead of upholding it,” he said.

In October 2006 Njonjo unsuccessfully attempted a political comeback by supporting opposition leader Raila Odinga.

Njonjo was one of the richest people in Kenya with extensive landholding across the country.

He also had interest in high-profile financial institutions including banks and insurance companies. – Courtesy of Kenya Yearbook Editorial Board