Hushing the culture of guns in the north’s restive regions

What greets you on a tour of the banditry-prone Kerio Valley is an uneasy calm punctuated by the buzz of human activity, which is a sharp contrast to the situation some years ago.

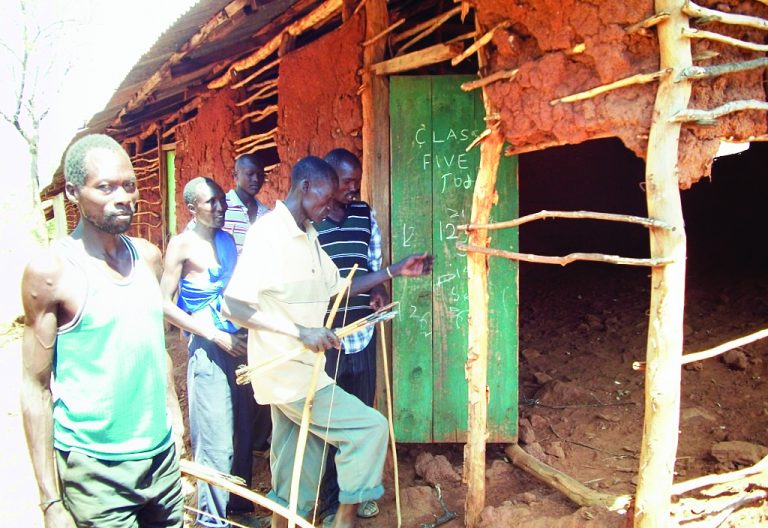

This has, for generations, been a battlefield for warring communities in the North Rift with almost normalised bloodletting. No parent dared to take their children to school here.

A survey by People Daily on a tour of the region however revealed that normalcy was being restored, with residents beginning to go back to their daily chores.

It has also not been an easy-to-come outcome with religious and political leaders, and elders from the region burning the midnight oil, sometimes risking their lives, to preach peace.

The first agenda was for leaders, herders and peace committees from the restless counties in the North Rift to embark on inter-generational dialogue. The agenda was simple- promote peaceful co-existence.

Through the Integrated Management of Natural Resources for Resilience in the ASALs (IMARA) project, cross-border grazing committees drawn from the warring Pokot, Turkana, Tugen and Marakwet communities were created.

Traditional mechanisms

Composed of 20 members, the committees were formed to engage herders and elders in conflict-resolution mechanisms in a bid to come up with grazing patterns and shun wrangles over pasture and water.

Traditionally, the premise of resource scarcity’dominates the debate on banditry in pastoral areas, where conflicts among communities have traditionally been linked to competition over scarce resources. Invariably, recurring drought exacerbates the situation because of its role in resource depletion.

The presence of armed groups has hindered access to grazing areas with instances of targeted raids and destruction of property being reported. Resource-based conflicts heighten especially during the end of the dry season and commencement of rains.

According to the programmes manager of Safer World, Elizabeth Atieno ,they came up with conflict management programs in West Pokot, Turkana, Baringo and Elgeyo Marakwet Counties.

“Elders and herders who are the real combatants were not meeting one-on-one but we are happy they have come together even with government officers and other stakeholders. We want to disarm them psychologically after listening to their grievances,” says Atieno.

Herders and elders in the troubled region are now reviving traditional mechanisms and grazing patterns to fight banditry and cattle rustling.

The impact of climate change in contributing to these vices is hard to overlook.

According to Atieno, climate change is increasingly affecting the communities’ adaptive capacities and traditional conflict management mechanisms had been weakened due to the intensity of conflicts.

She notes that they want herders to become champions and voices of reason in the community.

“We want to revive alternative dispute resolution mechanisms through herders. We shall sensitise them against the desire for revenge which has been intense as a result of prolonged drought,” she says, also acknowledging the value and contribution of traditional institutions and the role herders play.

The programme deals with resource management in realisation of the impact of climate change.

“We meet herders at grazing points, have constructive engagement with and identify their areas of grievances and potential for collaboration,” she says.

The programme seeks to cultivate a culture of peace in learning institutions. They have formed peace clubs in schools and actively cultivate good relationships among the learners. The need to have dialogue and minimise mistrust prevents counterattacks. By supporting cross-cutting dialogue, Atieno says, they minimise conflicts.

Samuel Kosgei from the Peace and Justice organisation agrees that cattle-rustling menace has escalated with the more devastating effects of climate change. Their organisation offers capacity-building to communities in the region on alternative dispute resolution.

“Inside peace committees we have grazing patterns and elders organise how grazing will take place. Grazing patterns go with rainfall patterns because we are not able to predict anymore since rains are erratic,” Kosgei says.

Herders who spoke to People Daily say they are now ready to engage in dialogue with their counterparts from the neighbouring communities.

A herder at Cheptulel area, Collins Charito, says there still is fear when grazing because of the illegal firearms owned by some residents in the region. He notes that all communities will soon realise the importance of preserving the grazing lands and learn a lot on pasture management. This will help them appreciate the fact that the survival of their animals will be ensured during the droughts.

Disarm warring communities

Charito insists that discipline among the young herders will be observed if they adhere to rules and regulations and promise to monitor law breakers. He proposes closing some areas for grazing to ward off resource-based conflict.

“We are ready for the herders committee so that we can talk to our counterparts,” he adds.

Samson Toilem, an elder, has called on the government to disarm all warring neighbouring communities, acknowledging that prolonged dry spells in the region have resulted in increased conflict.

“They should not arm one community alone. We need the National Police Reservists (NPRs) in both communities,” he says, noting that there is a need to start development projects like irrigation along the borders.

On Sunday last week, the communities, in a rare show of unity, converged at Tot in Elgeyo Marakwet county, which has been the epicentre of the conflicts, to celebrate the peace in the region.

President William Ruto, who was among the attendees, thanked the peace committees, religious and political leaders as well as elders for their efforts to preach peace.

“Peace is the greatest ingredient for any meaningful development to be achieved in any part of the country,” the president said, also thanking the security personnel in the region for their resilience and hard work.

“We have come here to celebrate the results of our peace efforts,” Ruto said.

The president promised that his administration will open up the vast region for development in terms of infrastructure for them to enjoy the full dividends of peace. He also assured parents and teachers that 26 schools, which had been vandalised by armed bandits have already been rebuild with the help of the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF).

According to the president, another 13 schools are in the process of being renovated for children to go back to their schools.

Religious role

Religion has also played a big role in restoring peace in the region with 13 churches and more than 10 schools being set up to bring peace and transformation in the region. The churches are using youthful preachers to spread the gospel of peace.

Through the Empowered Biblical World View Model (EBMV) and alternative livelihood programme of the Christian Impact Mission (CIM) organisation, Victory Life International Church, the government has been setting up schools and churches in hotspot areas within West Pokot, Baringo and Elgeyo Marakwet counties by supporting young children starting from the school-going ages of 3 and 4 years.

According to CIM Project Director Bishop Jimmy Gor, a new wave of transformation is sweeping in the troubled region.

“Our organisation has partnered with the government and other partners with the local community have embarked on supporting education and Christianity to open up the region to avert conflicts after many killings,” says Bishop Gor at Mosyolion area in Tiaty sub-county.

The clergyman notes that they make sure people in the area embrace change and with the increased enrolment of the young generation, incidents where youth get used to causing insecurity will soon be a thing of the past.

Massive security operation

“Education is a strong tool to root out banditry and cattle rustling. We deal with cultural and livelihood issues and mind-set change, which is paying off,” the bishop tells People Daily.

CIM founder and Director Bishop Titus Masika says the model begins with breaking the cycle of the kind of cultural life people have been living.

“You were born, circumcised, became a warrior and that becomes a life but now we want children to get born again, join PP1, PP2 and PP3 and continue with education, not the gun,” he says.

The government rolled out a massive security operation, coordinated by police and assisted by the military, in the North Rift early last year following the killing of more than 100 civilians and 24 police officers in six months alone.

The State termed six banditry-prone counties in the region among them Turkana, West Pokot, Elgeyo Marakwet, Baringo, Laikipia and Samburu as ‘disturbed’ and ‘dangerous’.