How I navigate my daughter’s sickle cell disease

Clifford Akumu @PeopleDailyKE

When she finally gave birth at 41 weeks, after a torturous experience, Caroline Akinyi, released a sigh of relief.

Akinyi, a mother of two, couldn’t hide her joy as she kept admiring her baby girl.

But before she gave birth, Akinyi a resident of Ongata Rongai in Kajiado County, had experienced trying moments during her pregnancy.

She had apparently inherited hypertension from her parents. And so when she conceived, her blood pressure was unstable.

Her gynecologist recommended that she didn’t need to go for induction but rather wait for the normal labour.

Unfortunately, she didn’t get any contractions until the 41st week. Worried and terrified, she switched to a new gynaecologist.

“When I went for another review with a different gynaecologist, I was informed I had foetus distress.

The doctor tried to induce me, but my blood pressure shot up and I had to undergo an emergency caesarean section,” says Caroline of the events of November 19, 2015.

Due to the foetal distress, Gloria, the baby- weighing 3.5kg was put on oxygen support for one hour. They would spend two days in hospital before being discharged.

“When we went home, she was okay, appeared normal and playful as any other child,” explains Akinyi.

On the sixth month, Akinyi was ready to resume work, confident in her daughter’s health having breastfed her exclusively for that duration. However, things took a different turn.

“We started realising that if she got sick overnight, when it reached morning hours she would develop high fever, restlessness, and would vomit a lot. The attack was on and off,” Akinyi narrates.

Doctors informed Akinyi that Gloria had a bacterial infection. But the s condition kept on deteriorating.

“When Gloria became sick at night, the following morning her high blood pressure dropped fast,” she explains.

It was only after running tests that they found that Gloria had sickle cell disease (SCD).

This is a genetic disease charaterised by a change in the shape of a red blood cell, from a smooth circular shape, to a crescent shape, which can result in the blockage of small blood vessels.

It took Akinyi some time to come to terms with Gloria’s condition, but once she did, she had counselling session with the doctor and her own research, she learnt more about the condition and how to manage it.

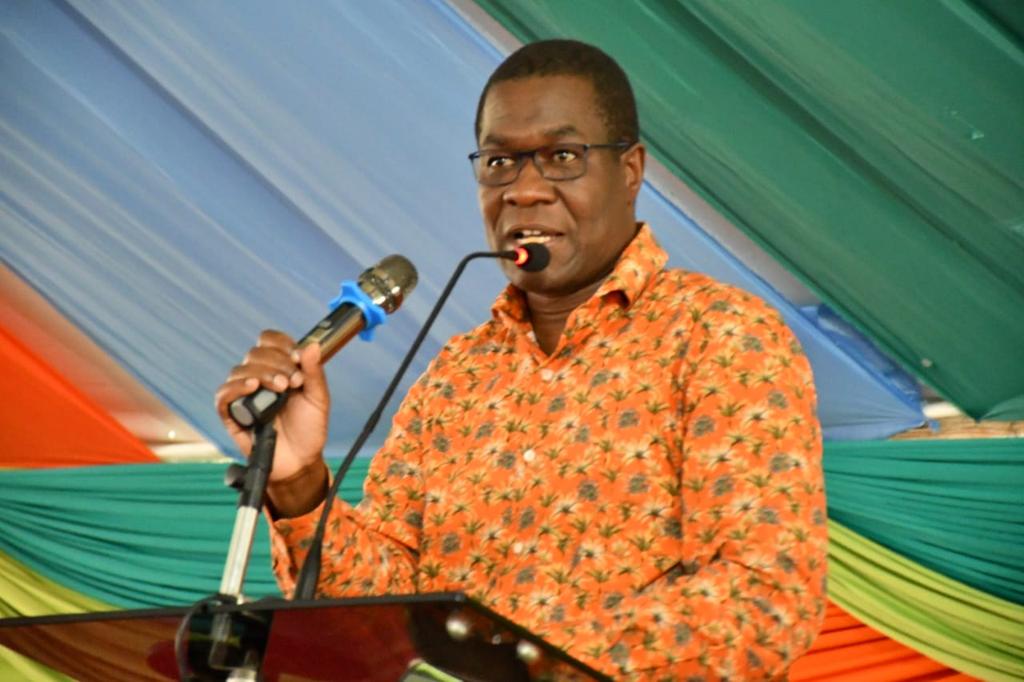

“It is not witchcraft, but a genetic disease. It must be present in your blood for you to get it and children are born with the disease,” says Dr Frederick Okinyi, consultant pathologist and haematologist.

Both parents must have high potency of the sickled cells in their blood for a child to get the disease.

“Under such circumstances, one stands a 25 per cent chance of getting a child who has sickle cell disease and a 25 per cent of getting a child who is healthy, and a 50 per cent chance of someone who is a carrier,” he adds.

As a carrier, you have the sickle cells in your blood, but do not show symptoms. As such, even if one were to get four children, not all of them will have the disease.

“It is akin to throwing a dart on the board and it hits anywhere. You can have all your children with sickle cell disease or you can end up with all of them healthy, which is rare or you can have them as just carriers,” explains Dr Okinyi.

About 240,000 children in Africa, are born each year with SCD. In Kenya, it is estimated that 6,000 children are born with the disease, according to the Ministry of Health.

Unfortunately, between 50 to 80 per cent of these children die before their fifth birthday. The recurrent pain and complications from the disease, can interfere with many aspects of the patient’s life.

Dr Okinyi, explains that sickle cell disease and malaria infections has co-relations because of the pressure of genetic mutation that was brought about by malaria infections.

The environment has then changed the red blood cells to a sickle cell shape, so that the malaria parasite cannot survive. And that is how people survive from malaria and by default develop mutations to acquire the sickle cell disease.

“Historically, people in Kenya migrated from different places. If you look at the climatic changes, especially in Africa’s equatorial belt has got la lot of rains, bushes that encourages the thriving of the mosquito parasites, which transmits the malaria.

In Kenya for example, the mosquitoes tend to thrive in warmer regions of the coastal and lake regions.

During such periods, malaria used to be common along the equatorial belt and the lake regions,” says the doctor.

In Kenya, for example, sickle cell cases are concentrated in Kisumu, Kakamega Bungoma, Kakamega rain forest, Kisii and coastal regions.

Burden in children

“Because of these factors, people got malaria infections. Usually in nature, there are transformation that are meant for survival instincts.

And because of these high malaria infections in those regions, the human being body adapted by causing genetic transformation that resulted in the development of sickle cell disease,” he adds.

The red blood cells stay in the body for 120 days, but with SCD, they cells do not.

“People with the sickle cell trait are less likely to have severe malaria infections. But the sickle cell carriers intermarried, mingled, socialised and that is how the disease has been spreading,” Dr Okinyi expounds.

A Wellcome Trust study conducted in Kilifi between January 2007 and April 2011 found that 128,000 infants within one year had sickle cell disease. It also found that 2.5 children per a 1,000 died of sickle cell disease.

However, there is still no clear data from the national government to paint actual prevalence of SCD because the country still lacks enough diagnostic kits in most parts of the country. Some hospitals are also ill-equipped.

According to Dr Okinyi, hospitals able to conduct diagnosis, such as private laboratories charge about Sh4,000 for the test, which is expensive.

Costly affair

“But we are still lucky because there are some rapid diagnostic point-of-care tests that can make diagnosis at only Sh1,500,” adds the doctor, who is also the chairman of the Sickle Cell Federation of Kenya-an umbrella body bringing together all organisations working on sickle cell.

Stigma among the parents is also to blame.

“The other reason we don’t have data is that many children die of the disease undiagnosed.

Many children under the age of five are confronted with diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. A child born with SCD is 10 times more likely to die,” notes Dr Okinyi.

Incidentally, when most of these children die at this age, people don’t even conduct postmortem to determine the cause of death.

Dr Okinyi continues, “Probably, if they presented with diarrhoea, malaria or pneumonia they will record that as diagnosis.

This could probably be diagnosed for SCD because the presentation of the disease begins when children are at the age of one year,” he adds.

For the country to obtain clear data on the sickle cell disease incidences, Dr Okinyi calls for a nationwide neonatal screening of children and having diagnostic kits available and affordable in most parts of the country.

“If you visit a place such as Coast, and meet 100 children, know that at least over two of them are likely to have SCD.

And places such as Kisumu, Kisii and Kakamega the estimate would be two to five for every 100 children,” he adds.

That lack of clear data on SCD makes it difficult to budget on and prioritise the disease.

Clinicians in most hospitals play a big role in terms of documenting and knowing the numbers.

However, most of it are hospital-based which only help particular institutions run their healthcare, according to Dr Okinyi, who recommends that children should be screened for SCD within the first year of birth.

When her daughter was below three years, Akinyi would visit the hospital thrice in a month or so.

She got scared when her daughter joined school because of her compromised immunity.

“The school was fortunately able to manage her well; she only had occasional flu and a bit of coughs, but this was managed at the school level by the school doctors and nurses,” Akinyi explains.

Support from close family members and at work kept her going.

“Fortunately I have good bosses at work. When I explained the condition of my daughter, I was accorded flexible timings,” says Akinyi, a nurse at a local hospital.

One of the major challenge that Akinyi and her family faced while managing her daughter, is financial strain.

“It has been expensive. I didn’t have any medical cover before, so I used to use cash and the hospital I was visiting had high consultation fees for seeing a specialist.

I am happy I was able to manage the cost. I took a health insurance cover last year and so far, it has really come in handy,” she says. Her siblings also supported her financially during her low moments.

Although other pharmaceutical companies are trying to subsidise cost of SCD drugs to ease access, the cost is still high, with patients spending between Sh20,000 and Sh80,000 within six months.

Besides funds, other challenges in management of SCD include health seeking behaviour, unavailability of drugs and blood for transfusion among others.

People with SCD are also at risk of severe disease if infected by Covid-19 due to their compromised immunity.

“It was so scary. But we had confidence because they were indoors online learning and at school the management has adhered to the ministry of health protocols . We take precautions. But the fear is still there, ”Akinyi says.

Curative options

Dr Padmaja Lokireddy, haematologist and bone-marrow transplant consultant at Hydragad Apollo in India explains that simple painful crisis are treated as a standard means by giving oxygen, fluids and treating the infections.

“A situation where a child is getting admitted in hospital twice or thrice in a year then one needs to think about a curative option-which calls for a bone-marrow transplant.

Not all sickle cell patients need a bone-marrow transplant. If a child or an adult gets a stroke because of sickle cell or they are getting admitted three or four times a year, then it’s an indication to go for a transplant,” Dr Lokireddy.

The transplants are best done when children are younger, below 10 years, she advises.

“The more and more blood transfusion one takes, the more the complication with the bone-marrow transplant because of the antibodies and make it virus infectious,” she notes.