Kibaki replaced sanity in public office with presidential orders

During his inauguration as Kenya’s third president on December 30, 2002, Mwai Kibaki placed restoring sanity and order in the public service third on his priority list.

The public service was up to the eyeballs in corruption, lethargy was the order of the day and accountability was an alien concept.

This was the legacy of the previous two administrations, both of which he served in top positions including as Vice-President and Finance minster. But in the 10-year hiatus that he had served in the opposition, Kibaki had sold himself as an agent of change, who would right the wrongs of his predecessors; Daniel arap Moi and Jomo Kenyatta. Moi’s style – the centralisation and personalisation of power – laid the foundation for dictatorship, human rights violations and a public service that was more in the service of the president than of the public.

Moi had criminalised competitive politics and criticism of his leadership. Throughout the 80s to 90s, security forces, particularly the police, were used to suppress any criticism of his government. To ensure his grip on power, Moi had systematically usurped functions of the other institutions of governance to the extent that the principle of the separation of powers became ineffectual.

As a result, public institutions operated on the whims and desires of the President and served him an his cronies’ interests. Moi delegated little or no responsibilities as he personally became involved in almost everything in the country.

A complete overhaul of the governance system was, therefore, high on Kibaki’s agenda as he took the oath of administration at Uhuru Park.

Kibaki promised to only appoint qualified people to public office and pledged to restore the authority of Parliament and independence of the Judiciary.

“We want to bring back the culture of accountability and transparency in public office. The era of anything goes is gone. I believe the government exists to serve the people, not the people to serve the government,” Kibaki said to a thunderous applause from the crowd. First to go was the personality cult style of leadership that had been hallmark of the Kenyatta and Moi presidencies.

A symbol of this change, Kibaki scrapped the tradition of putting the President’s portrait on the country’s currency. He also resisted attempts to have educational institutions, roads, hospitals and public institutions named after him.

Resists attempts

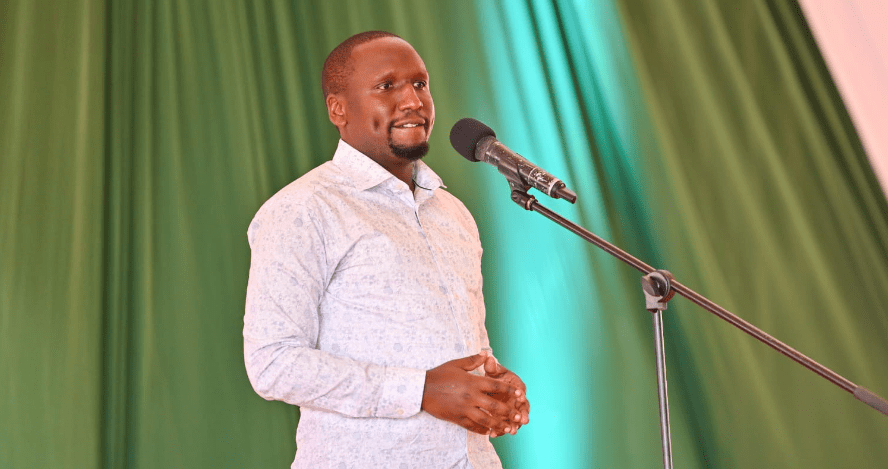

“One of the first traditions President Kibaki broke away with was to stop the culture of having praise songs composed in his honour and the domination of public media news by reports of his activities, however, mundane or routine,” Chris Murungaru, who served in Kibaki’s government as Internal Security minister told People Daily in an interview.

After discarding the mechanisms that had been established to glorify those in authority, Kibaki disbanded harambees, a noble concept that had been turned into a political tool and an avenue for corruption. The Public Officers Ethics Act, 2003 banned MPs and Cabinet ministers from presiding over harambees. It was even claimed that in some cases, politicians diverted money collected in fundraising meetings to fund their campaigns.

Murungaru says that although some criticised him as hands-off and aloof, Kibaki allowed Government institutions and the people he appointed to operate independently. “He was only interested in positive results and unlike Moi, he never meddled in the daily operations of State agencies. In fact, it is this hands-off leadership-by-delegation style that made the technocrats he appointed succeed since they were determined to prove their worth,” Murungaru adds.

Positive results

He says that during the Kibaki decade, ministers and chief executives of State corporations enjoyed powers that their predecessors who served in the previous governments never did. This kind of freedom allowed the emergence of super ministers like John Michuki and Karisa Maitha (both now deceased) who effected far-reaching reforms in whatever ministerial dockets they were assigned.

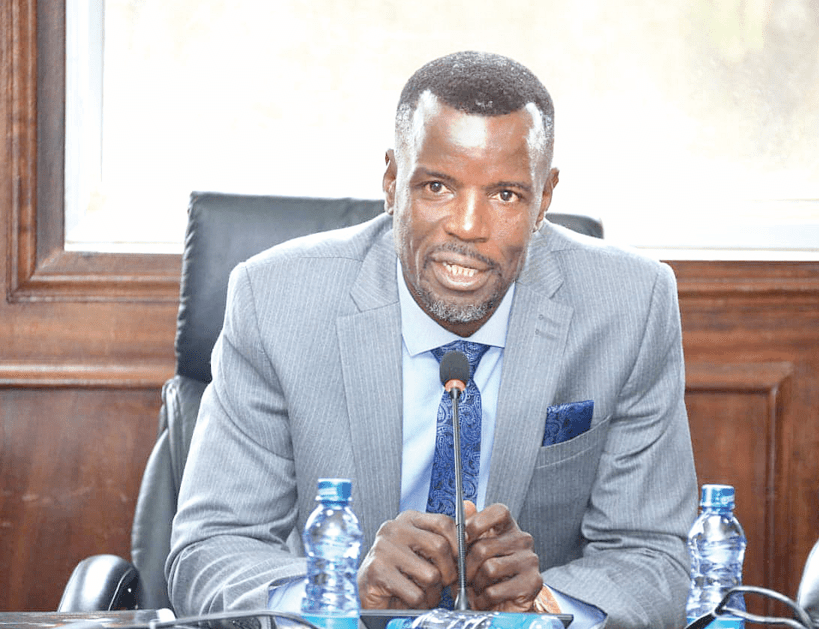

Some political scientists believe that it was Kibaki’s passive leadership style that ironically brought about the institutional and economic reforms the country needed. “A hands-off approach to business unleashed an economic recovery as companies thrived unmolested by the government for the first time in years. Free speech and a rumbustious media also blossomed as the repression of the Moi era faded away,” Dr Oscar Otele, a lecturer in political science at the University of Nairobi observes. Within a short time, the National Assembly and Judiciary, the two institutions that had been muzzled by the Moi administration, got their voices back. Kibaki also revived key economic institutions such as the Kenya Cooperative Creameries, Kenya Meat Commission and Kenya Railways Corporation that had been run down during the Moi years.

With a stroke of a pen, the Kibaki administration recovered the Kenyatta International Conference Centre that had been taken over by Kanu, and turned it into a parastatal under the Ministry of Tourism then headed by Raphael Tuju.

As respect for constitutional offices and other government departments returned, the provincial administration, which had been used by his predecessors to stamp their authority, started to lose relevance.

In his early days as president, he unveiled the Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation, which as a result enabled GDP to expand by 5.8 per cent in 2003 compared to 0.4 per cent at the time he became president.

He also went on to launch the Vision 2030 projects aimed at reaching a GDP growth of 10 per cent annually and transforming Kenya into a middle- income economy by 2030.

Perhaps one of his most ambitious projects was the launch of the Free Primary Education programme and provision of free drugs for malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/Aids. “All these programmes succeeded because of the discipline and sanity Kibaki had instilled in the governance system. He had brought to an end the era of impunity in the public service and enabled transparency and accountability to prevail,” Otele says.