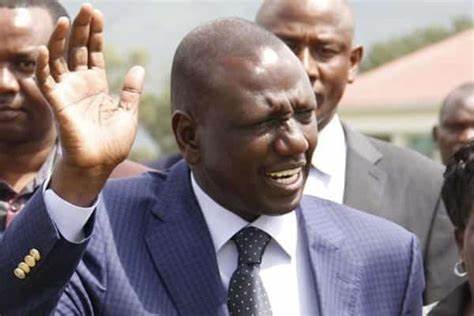

Ruto crisis is a legal, public participation issue

The root of the crisis facing President William Ruto’s government emanates from the failure to fulfill many promises made during the 2022 General Election campaigns.

Matters have not been helped by his vitriolic attacks on the Judiciary, accusing unnamed judges of corruption, allegations that have been widely condemned.

What has raised public ire is Ruto’s public declarations threatening to defy court orders and imputing corruption allegations in the Judiciary, claims that are supported by his political allies.

The President’s wrath has been provoked by a series of court rulings that went against his pet projects and the punitive tax measures contained in the Finance Act, 2023. Some of the projects arose from promises made during the election campaign.

Although the bad blood between the Executive and the Judiciary was somewhat cooled by the recent joint meeting involving the President and the Speaker the National Assembly, the crisis facing Ruto has deepened.

Furthermore, despite the Executive’s concerted attempts to defend the meeting, public suspicions have been heightened by its real intent coming after the attacks on the Judiciary and perceptions that the Legislature has been “captured”.

Last Friday, the President suffered three major legal blows. First, the Court of Appeal stopped the collection of a levy to fund his much-criticized housing programme, despite his aggressive campaign to implement it.

However, legal and financial questions have been raised about its implementation. His attempts to publicly campaign for the project have drawn complacent reactions. Now the project faces stringent public scrutiny.

Second, the High Court halted the deployment of 1,000 police officers to Haiti, a promise Ruto made during the United Nations General Assembly. Third, the High Court admitted a case challenging National Assembly Speaker Moses Wetangula’s ruling on which side has the majority, hence the upper hand in sharing of seats and committee leadership positions.

The Opposition, civil society and the public have condemned the statements, saying they were illegal, an affront to the Constitution, and did not involve public participation.

The public (citizens) have sought justice through the courts as the final arbiter between them and what they consider a defiant Executive acting to their detriment and the independent arms of government.

In taking their cries to the Judiciary, the public is exercising its rights anchored in the Constitution to question decisions that affect them by expressing their free will through the principle of public participation.

A number of other court actions have been instituted seeking to stop or reconfigure the implementation of many of the Ruto government’s programmes in recent months.

They include the rollout of the “Maisha Namba” new identity system, a planned healthcare system under the Social Health Insurance Fund, the appointment of 50 Chief Administrative Secretaries and the planned privatization of 11 State firms, and Mombasa and Lamu ports.

The public expect the Judiciary to be the final arbiter to enhance the people’s role to influence their future and assume responsibility for it, instead of being the object of or at the receiving end of decisions by others.

Participation in political and public affairs relates to the exercise of political power, in particular the exercise of legislative, executive and administrative powers that cannot be left alone to the Executive and a compromised Legislature.

The right to equal participation in political and public affairs is an individual right and also has a group or ‘peoples’ dimension.

—The writer comments on governance issues – albertoleny@gmail.com