Of giving, politics and the battle for soul of the church

In traditional African society (before the 19th century), giving was deeply embedded in communal living, where wealth was not an individual possession but a shared resource.

Reciprocity and collective responsibility guided the distribution of resources, ensuring that no member of the community was left in need. Elders played a central role in overseeing the equitable distribution of food, livestock, and other essential goods, while communal labour, such as ‘harambee’ in East Africa, reflected the spirit of cooperation and mutual aid.

Gifts were often given in kind rather than in cash, including food, livestock, or labour, and were seen as a means of strengthening social ties rather than gaining prestige or power. Giving was a moral duty, emphasising harmony and interdependence within the community.

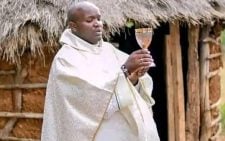

With the advent of Christianity and Islam in Africa (from the 1st century AD for Christianity and the 7th century AD for Islam), religious teachings on giving began to influence traditional practices. The Bible and the Quran reinforced the values of charity and communal support, encouraging believers to give as an act of worship and love. The early church emphasised communal sharing, much like traditional African societies, as seen in Acts 2:44-45, where believers pooled their resources to support those in need.

Likewise, Islamic zakat, formalised in the 7th century, ensured that wealth was redistributed to the less fortunate. These religious principles resonated with existing African values, strengthening the culture of generosity and hospitality.

Transformative solution

The advent of colonial period (late 19th to mid-20th century), witnessed new economic structures that disrupted traditional forms of giving. The monetisation of African economies and the introduction of wage labour shifted the nature of generosity from communal sharing to monetary contributions. Missionary churches encouraged structured forms of giving such as tithing, while colonial governments sometimes co-opted religious institutions to pacify communities through controlled charity.

Christianity, propelled by missionaries like Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann, intertwined with British colonial structures, embedding religious, educational, and healthcare institutions deeply into local culture. This relationship persisted beyond colonial rule, with Christianity becoming a hub of governance and community service, fostering a symbiotic relationship between the church and the administration.

History reminds us that this dynamic is not new. In medieval Europe, monarchs funded cathedrals as displays of piety, yet these same rulers often oppressed the very people who built those churches. Similarly, during the colonial era in Kenya, some Christian missions received State support to pacify communities, weakening the church’s prophetic voice.

Now, in post-colonial Kenya, churches risk becoming complicit in modern forms of political patronage if they accept donations without questioning the donor’s broader actions. Can the church truly call itself a beacon of Christ’s love if it remains silent on injustice in exchange for political contributions?

The Bible teaches that giving and building the church is an act of worship, an expression of love, and a demonstration of stewardship. It is not limited to monetary contributions but encompasses time, talents, and resources offered to strengthen the body of Christ and serve others.

Scripture calls for giving with a generous heart, as seen in Paul’s words to the Corinthians: “Each of you should give what you have decided in your heart to give, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver” (2 Corinthians 9:7). This kind of giving is voluntary and joyful, flowing from gratitude rather than obligation.

The practice of tithes and offerings, as commanded in Malachi 3:10, provides for the church’s needs and sustains the work of ministry, reflecting the early church’s communal spirit where believers shared what they had to care for the needy (Acts 2:44-45).

Yet, when this biblical vision of giving intersects with public donations by politicians, tensions emerge. While public giving can indeed meet genuine community needs—funding church buildings, schools, or local projects—it often carries the weight of political ambition. Politicians’ donations are frequently made in highly publicised settings, blurring the line between altruism and image management.

Jesus’s teaching in Matthew 6:1-4 warns against practicing righteousness for public applause, emphasising that true giving should be discreet and selfless. Public donations, when entangled with political motives, risk becoming less about love for neighbour and more about cultivating voter loyalty or reinforcing patron-client relationships.

Between the 1970s and early 2000s, politicians dedicated weekends to fundraising for community necessities such as student bursaries, school infrastructure, and farmers’ cooperatives, among other community needs. These endeavours significantly contributed to social and economic progress. However, a noticeable shift occurred in the mid-2000s, as politicians increasingly pivoted towards church fundraisers. This transition sidelined previous community-oriented initiatives, prompting concerns about its broader implications.

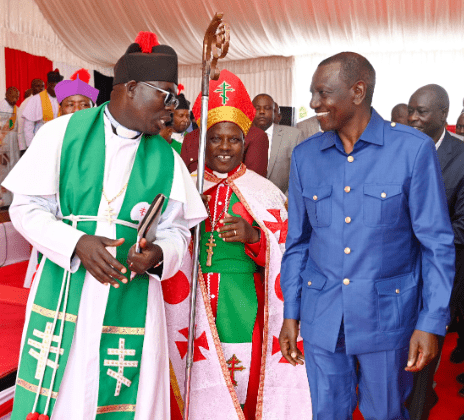

Today, Kenyan politicians frequently engage in church gatherings, leveraging religious events for political mileage. Social media platforms serve as showcases for their involvement in religious activities, highlighting the significant influence of faith in political circles.

The President’s active participation in these church fundraisers indirectly influences other politicians to concentrate on church harambees. His involvement sets a precedent, encouraging politicians to follow suit to gain favour with religious communities and the broader public.

Can a gift truly be called generosity if it comes with political strings? When a politician donates funds to a church, are they investing in the spiritual well-being of the community, or are they laying a foundation for future political endorsements? These questions feel particularly pressing when viewed alongside recent events.

2024 Demos

In June 2024, Kenya witnessed a powerful movement led by Generation Z protesters who challenged proposed tax hikes through the “Occupy Parliament” protests. Mobilising through social media platforms like TikTok, young activists organised peaceful demonstrations, demanding accountability and justice from a government they felt was exploiting its people.

As these youth risked their lives for systemic change, some politicians continued to present themselves as benefactors of the community, donating to churches even while supporting policies that deepened inequality. How do such public displays of charity reconcile with the brutal police crackdowns on peaceful protesters?

Reports surfaced of authorities using live bullets, with some deaths allegedly covered up by labelling gunshot victims as traffic accident casualties. In such moments, the stark contrast between biblical giving and political patronage becomes painfully clear. The Gen Z protesters embodied the spirit of Acts 2—a collective movement seeking justice and shared welfare—while the State’s response revealed a reluctance to relinquish control, even as it performed public gestures of generosity.

In the heat of the Gen Z movement, the president directed in July 2024 that no State officer would be allowed to participate in fundraising activities going forward. “The Attorney General is hereby directed to prepare and submit legislation to this effect and develop a mechanism for structured and transparent contribution for public, charitable, and philanthropic purposes,” he declared.

Politcal donations

However, this directive led to a brief pause before normalcy resumed, with the president himself leading in gifting Jesus Winners Ministry Church and AIC Annex Sh 20 million each. This risks a return to youth protests, as the government’s stance on political donations remains unclear.

Public figures can align their giving with biblical principles if they approach generosity with humility and genuine concern for the well-being of others. Rather than using donations to consolidate power, they can prioritise the needs of the community, encouraging collective responsibility and shared ownership of development.

Giving can still be public, but the focus should be on impact rather than recognition. Churches, too, can play a role in holding leaders accountable, graciously receiving gifts while advocating for justice and resisting exploitation.

In this light, the act of giving remains a powerful force for building the church and society. But its true value lies not in the size of the gift or the status of the giver, but in the sincerity of the heart and the pursuit of God’s vision for a just and compassionate world.

The writer is a PhD is a History Lecturer and UASU Chapter Trustee at Alupe University-Kenya.