ODM rebels move from political pariahs to vindicated visionaries

In politics, boldness is often praised – until it isn’t. This paradox defines the experience of ODM leaders who first crossed the aisle to support President William Ruto.

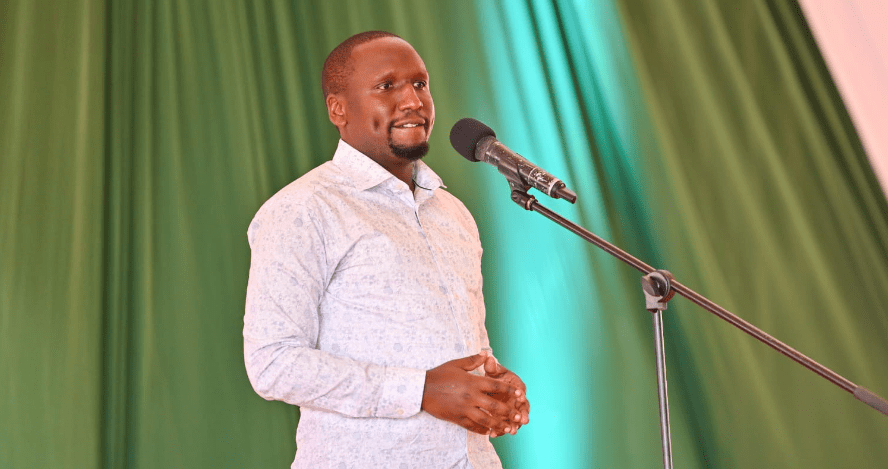

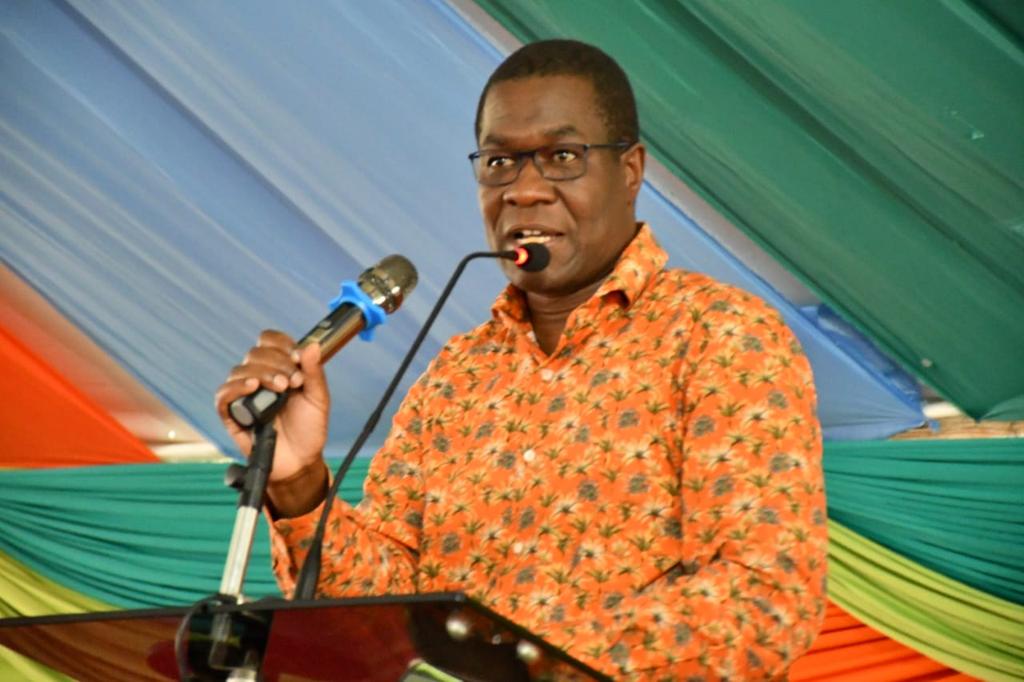

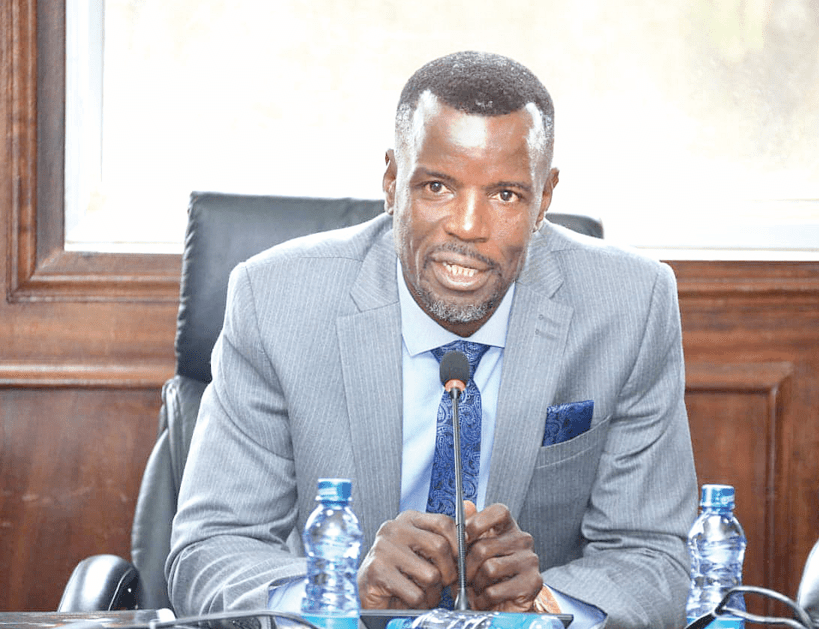

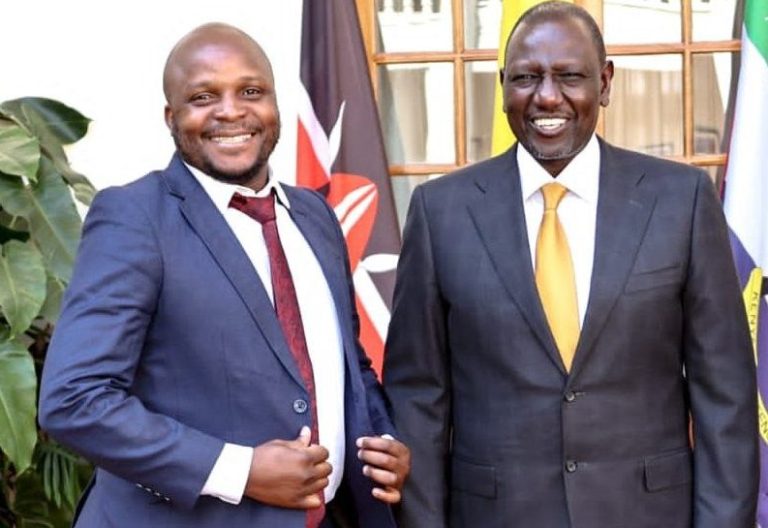

The pioneers included Kisumu Senator Tom Ojienda, Rongo MP Paul Abuor, Uriri MP Mark Nyamita, Bondo MP Gideon Ochanda, Suba South MP Caroli Omondi, Gem MP Elisha Odhiambo, and Langata MP Felix Odiwuor (Jalang’o).

Elected under ODM, they broke with their party to work with Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza administration, sparking immediate backlash and threats of expulsion.

What once appeared a risky gamble is now being reframed by unfolding events.

The broad-based government (BBG) has reshaped Kenya’s political terrain, offering a governance model rooted in unity and development.

Unlike traditional coalitions that are transactional and short-lived, the BBG represents strategic evolution in Kenya’s democratic journey, acknowledging that development cannot be hostage to endless political rivalry.

Within this context, the early rebels’ move now mirrors the path many opposition leaders are taking.

Influential ODM leaders – John Mbadi, Opiyo Wandayi, Hassan Joho and Wycliffe Oparanya – are now Cabinet secretaries. Previously vocal critics of Ruto are part of a political architecture favouring collaboration over resistance.

Ironically, the early rebels find themselves in a politically ambiguous space. They were too early for the handshake but too late to be seen as insiders in the formal power-sharing process.

Not fully trusted by ODM and not yet fully embraced by the government, they occupy an uncomfortable middle ground.

Yet they weren’t wrong. Senators like Ojienda and MPs like Ochanda argue they were simply ahead of their time.

The political vilification they endured is quietly being walked back by colleagues who, under the BBG umbrella, are doing exactly what these leaders were once criticised for: working with the government for constituents’ development gains.

The BBG has legitimised a mindset that prioritises country over party, demonstrating that effective service doesn’t require shouting from opposition benches.

You can cross the aisle and negotiate results. This pragmatic cooperation, once treated as betrayal, is becoming the new normal in Kenya’s maturing democracy.

The lesson is clear: in Kenyan politics, timing is everything. Being first isn’t always the same as being right – or being rewarded.

These leaders carried the weight of defiance without BBG’s structured transition benefit, but their role in softening the ground for cross-party collaboration shouldn’t be dismissed.

Their early gamble made it politically easier for others to follow. Now, as they navigate this reality, the challenge is reinvention.

They must reposition themselves within a government structure that welcomes the cooperation they once fought for alone. They are the bridge between Kenya’s combative political past and its cooperative future.

The BBG isn’t perfect, but it’s progress.

As democracy scholar Larry Diamond notes: “The consolidation of democracy is not merely about holding elections, but about building institutions that foster peace, accountability, and collective progress.”

This is the BBG’s essence. Kenya first.

The writer is a media consultant, a senior writer at the People Daily and a regular commentator on governance and democracy issues