Latter-day hip-hop is all style and little substance

I’m a reluctant second-hand consumer of rap, that inescapable musical element of world-conquering hip-hop culture. I’m tortured with it in matatus, in other people’s cars or from their mobile devices, and in bars.

It’s as if younger people play it just to spite uncomprehending seniors – a way of mooning them or showing them the middle finger.

With artistes speaking (can’t say singing) rhythmically over rapid, repetitive beats, rap is a grating musical style that’s difficult to appreciate.

Critics also point to sexually explicit and violent lyrics that glorify drug use, misogyny and materialism, and reinforce negative stereotypes.

What emerged from a back-to-school party in the Bronx, New York City, in the 1970s with DJ Kool Herc and was advanced by the likes of Afrika Bambaataa and Sylvia Robinson (incorporating DJing, fashion, graffiti and a strange vocabulary) has evolved and spread to many parts of the world that its pioneers knew next to nothing about.

But with little or no knowledge of hip-hop’s history – or what’s called the ‘fifth element’ of hip-hop, a certain consciousness and cultural understanding – can there be meaningful appreciation of or authentic participation in that culture?

Listen to much of contemporary American rap. What’s left to say about it?

It’s a deranged response to the American experience, which is impenetrable for most of us except maybe as a subject of passing academic musing.

It’s impossible for the non-American creator or consumer of rap to enter the Black-American or Latino experience that birthed hip-hop.

Without understanding the historical marginalisation of those two minority groups – an alienating experience that taught generations not just the survival shield of defiance but also a sinister self-hatred – the non-American rapper can’t meaningfully participate in hip-hop culture.

But there’s no denying hip-hop’s phenomenal global reach. Pioneer rappers recognise this and have expressed mixed feelings about it.

Some have cited pride in its appeal and its potential to bring socio-political change, while others have worried about authenticity (which is not a trivial matter).

On the positive side, Bambaataa, for example, has embraced hip-hop’s global appeal through his Universal Zulu Nation organisation, which he founded in 1973.

Meanwhile, Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest has voiced concern about cultural appropriation, telling an interviewer in 2018 that as hip-hop reaches the corners of the world, “sometimes the history and context get left behind. People take the style but miss the substance”.

The pioneers acknowledge that this thing that they created on the streets and in the basements of New York City has spun out of control and is no longer theirs.

In speaking to others about rap, I’m often advised to try to be more appreciative of it and to develop the nuanced perspective of the pioneers.

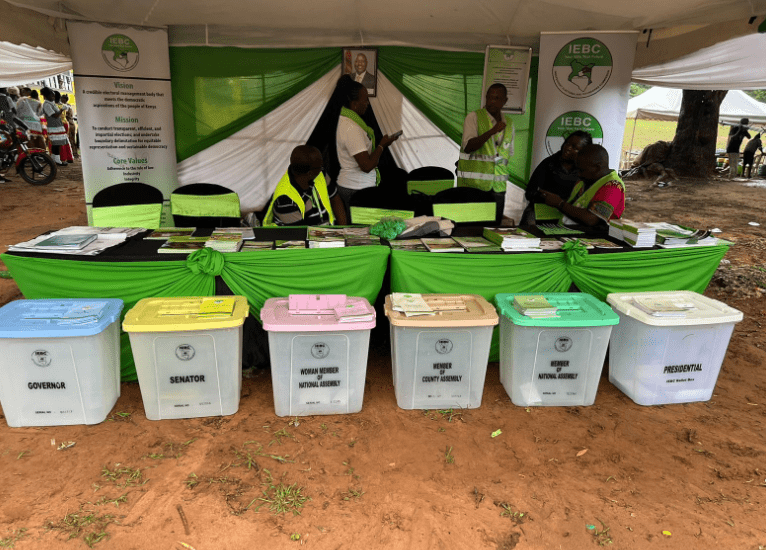

Kenya, for example, I’m reminded, has a vibrant hip-hop scene that has developed its own unique identity.

Some Kenyan rappers have taken up the genre and supposedly made it their own, including Khaligraph Jones, who has won some African continental awards, and Octopizzo, who borrows bits from traditional Kenyan music.

But these artistes, however innovative they may be, can’t enter the consciousness that spawned hip-hop, and their output will always come across as imitative, self-conscious displays.

They’re trying to channel their distinctly different urban experience through an appropriated artistic form – and that causes me immense intellectual discomfort.

The writer is a Sub-Editor with People Daily