How Kenya can exploit her huge mining potential

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP27) meeting in Egypt has come to an end. It’s quite a mouthful, perhaps capturing the gravity of the situation the world faces today.

In the face of undeniable climate change, a persistent Covid-19 pandemic, a looming recession and once in a generation inflationary pressure, we are all wondering what comes next.

The African Development Bank noted back in 2019 that despite Africa’s low contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, it remains the most vulnerable, primarily due to our reliance on rain-fed agriculture and fragile economies. Remarkably, the Centre for Climate and Energy Solutions notes that energy production of all types accounts for 72 per cent of all emissions.

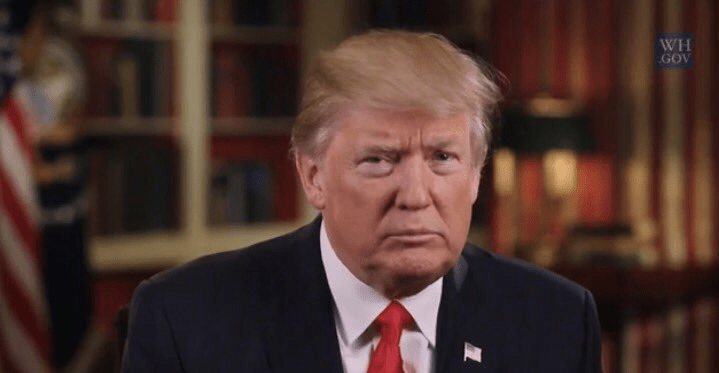

China, the US and the EU together generate over 75 per cent of global emissions. The entire African continent is responsible for less than 4 per cent. In other words we will bear much of the climate change risk with very little of the reward.

As the saying goes, it is always darkest before dawn. Carlos Lopez, former executive secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, noted in a recent interview that the West’s appetite for green hydrogen and strategic minerals like copper, lithium and cobalt will not be satisfied without Africa. The African challenge is whether this time we can negotiate from a position of strength and be part of the value chain.

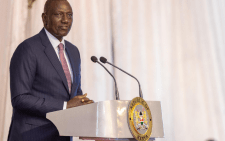

One of the most significant deals signed at COP27 was between Kenya, led by President Ruto and Fortescue Future Industries (FFI), led by Andrew Forrest, the Australian mining billionaire. The deal aims to fast-track development of an affordable green fertiliser supply chain and other green hydrogen-based industries. It includes planned feasibility studies that could scale up renewable electricity generation for green industries by up to 25GW, ultimately producing up to 1.7 million tonnes of green hydrogen per year for export. Hydrogen is considered green if its production is powered by renewable energy. It is a game changer in replacing fossil fuels.

Back to the value chain. Combatting climate change will need a massive amount of critical or strategic minerals essential to the green revolution. Examples include quartz, niobium, graphite and rare earth elements. These are found in wind turbines, solar panels, smartphones and electric vehicles.

Kenya appeared to be on the cusp of a mining boom in 2013 but a combination of local mistrust and international economics cost us that opportunity. All is not lost. We have a potentially world class niobium and rare earth deposit in Kwale. The country is also awaiting the results of KenGen’s work to explore the extraction of lithium from geothermal fluids. We could once again have the chance to literally dig ourselves out of our economic hole and be at the forefront of contributing to the fight against climate change.

The three crucial ingredients for success are geology, policy and partnerships. Geology is a divine gift. Unlocking it requires detailed exploration. The much touted airborne survey is a start but more is needed. Mineral deposits are only economically viable if they occur in sufficient quantity and quality, are feasible to extract and have a ready market.

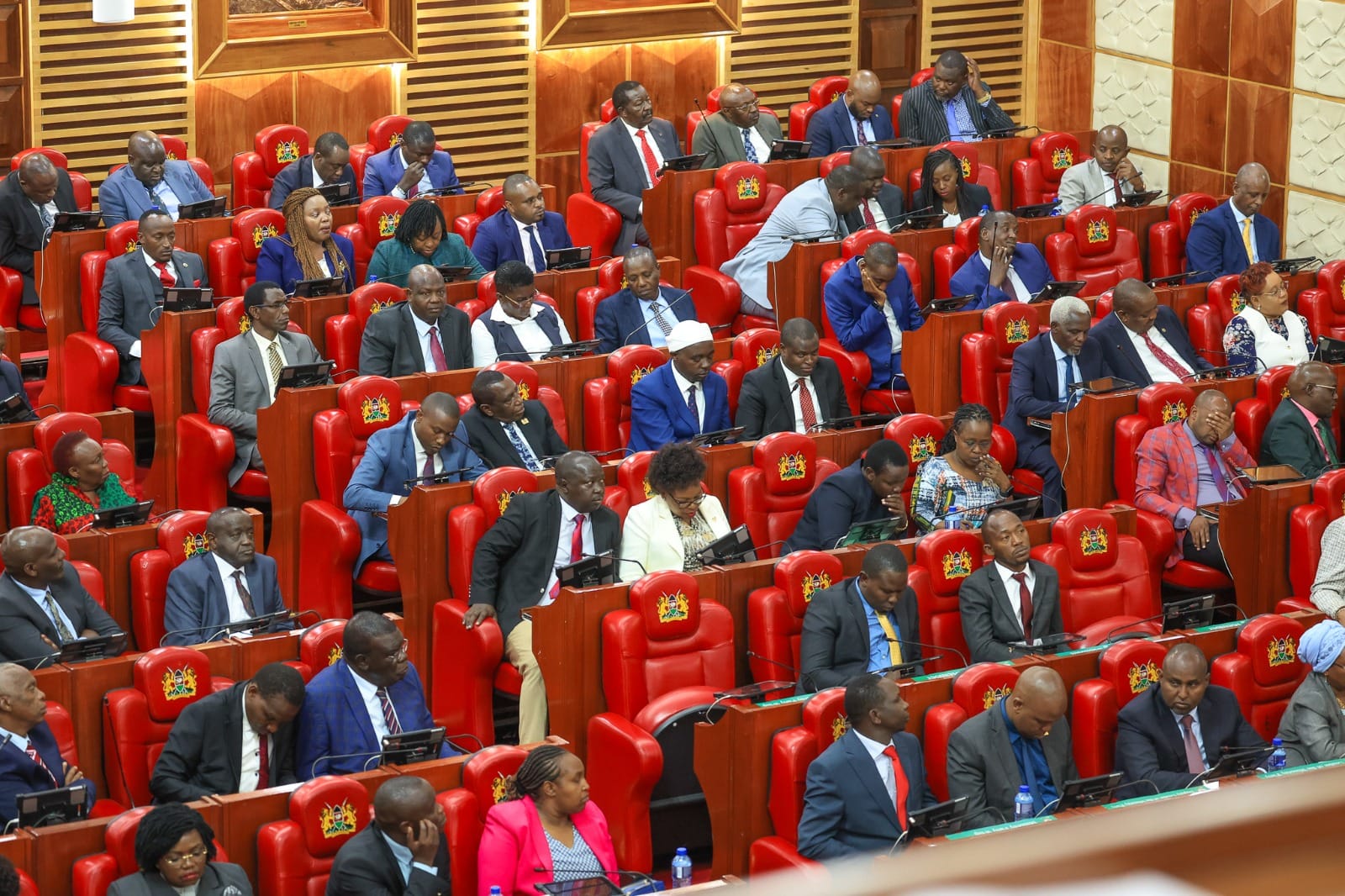

Policy is crucial. There will always be challenges – land use, environmental considerations, technical capacity, geo-politics and local community buy-in.

The Mining Act 2016 is not perfect but addresses many of the key issues. It also provides a crucial investment vehicle in the National Mining Corporation (NMC). A credible NMC will derisk the sector as an investment partner navigating the bureaucracy. Ultimately the government, industry and communities must seek a win-win outcome for successful mineral exploitation.

Finally, partnerships are crucial. Mining investment is always substantial. Base Titanium in Kwale was built at a cost of $300 million (Sh36 billion). Base reported revenue of $87 million (Sh10.7 billion) in 2021/22 alone. Mining is a global industry combining technology, economics and politics. The industry needs to cultivate local and international partnerships to successfully develop these deposits that the world now desperately needs and is prepared to pay top dollar for.

Our first attempt at establishing a significant mining industry contributing 10 per cent of our GDP was unsuccessful. They say lightning never strikes the same place twice but this time it just might!

—Cliff Otega is a public policy analyst