Examination rankings stain purpose of national education

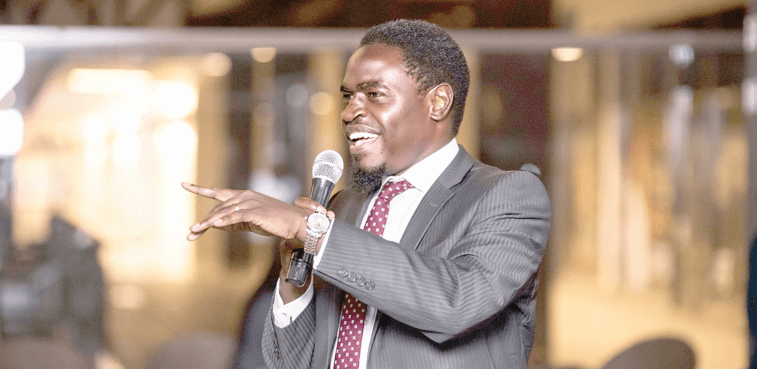

Former Education Cabinet Secretary Prof Jacob Kaimenyi made two landmark decisions with potentially immense consequences for education.

Kaimenyi, who served in the Uhuru Kenyatta administration, restricted secondary school fees to the current Sh53,000 for national schools and lowered fees ceilings for other categories of secondary schools. He also discontinued ranking of students on the basis of national examinations results, as had been the practice since 1994.

Before rankings ended, the ministry used to provide, upon release of KCPE and KCSE examination results, detailed information about the top 100 candidates nationally.

However, Kaimenyi and Basic Education Principal Secretary Dr Belio Kipsang stopped the practice in 2014.

The two were not the first to raise questions about the educational value of ranking of students.

Prof George Eshiwani, a former vice chancellor of Kenyatta University, had questioned the rankings in 1994. He did this in his capacity as the chair of the Kenya National Examinations Council.

Speaking to secondary school heads in Eldoret, he said ranking schools in KCPE and KCSE was misplaced because students, not schools, sat the examinations.

Instead of ranking schools, he advised, KNEC should instead rank students nationally.

I covered the function under the auspices of the Kenya News Agency (KNA). I was based in the then Uasin Gishu district.

The government didn’t end the rankings. It restricted it to students and not schools. This was, however, the first sign that there was something fundamentally wrong with ranking in national examinations.

It was the 2001 “Report on Student Discipline and Unrest in Schools”that recommended that the government stop ranking schools and students in national examinations.

The report argues that the rankings had created practices that were detrimental to good teaching and learning practices; it was causing unnecessary pressure on schools and students to excel in examinations.

It was Kaimenyi, some 15 years later, who put a stop to ranking students and, by default, schools altogether.

Eshiwani’s ban on ranking schools had not worked either. These rankings meant identifying the schools that the best-performing students had attended.

So, the pressure to have their students ranked meant that schools did everything within their power to ensure their students got top grades.

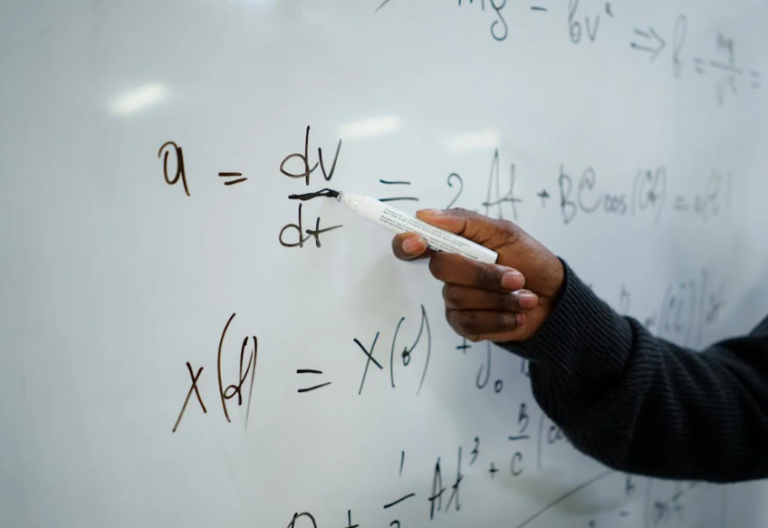

As with ranking of any sort, the temptation to focus on passing examinations is higher. The necessary balance between teaching, learning and testing is tilted. You see more testing and less teaching and learning in most schools to prime students on how best to tackle examinations and not, strictly speaking, to learn.

The 2001 report addressed this problem exhaustively. The holistic education that the government envisions children to have suffers when there is an imbalance between teaching, learning and testing.

In banning rankings, Kaimenyi sought to reclaim education at the school level back to its compass: developing the intelligence and character of students to their utmost limits possible.

The government has stuck to the spirit of the report, as affirmed by the discontinuation of rankings, be it of students or schools, when national examinations results are released.

Regrettably, however, media houses have stained this policy by hunting out students who excelled in any given examination and publishing them. The media doesn’t just publish their names; they also publish the schools they had attended. This negates the government policy on banning ranking altogether.

Clearly, the fanfare denies Kenya the opportunity to look at many issues — away from ranking of individual students and schools — about the state of education.

Unquestionably, the discontinuation of officially sanctioned rankings was urging us to look at the bigger purposes of a national education system such as ours.

Are we properly educating the next generation? Are we attaining the stipulated benchmarks for learning? Are the controls to this effect effective? What else can we do to enhance children’s access, equity and quality in education? What are the examination results, looked at from a social justice perspective, telling us?

— The writer is a Communication Specialist; buhere2003@gmail.com