Call to award oppressed minorities own counties

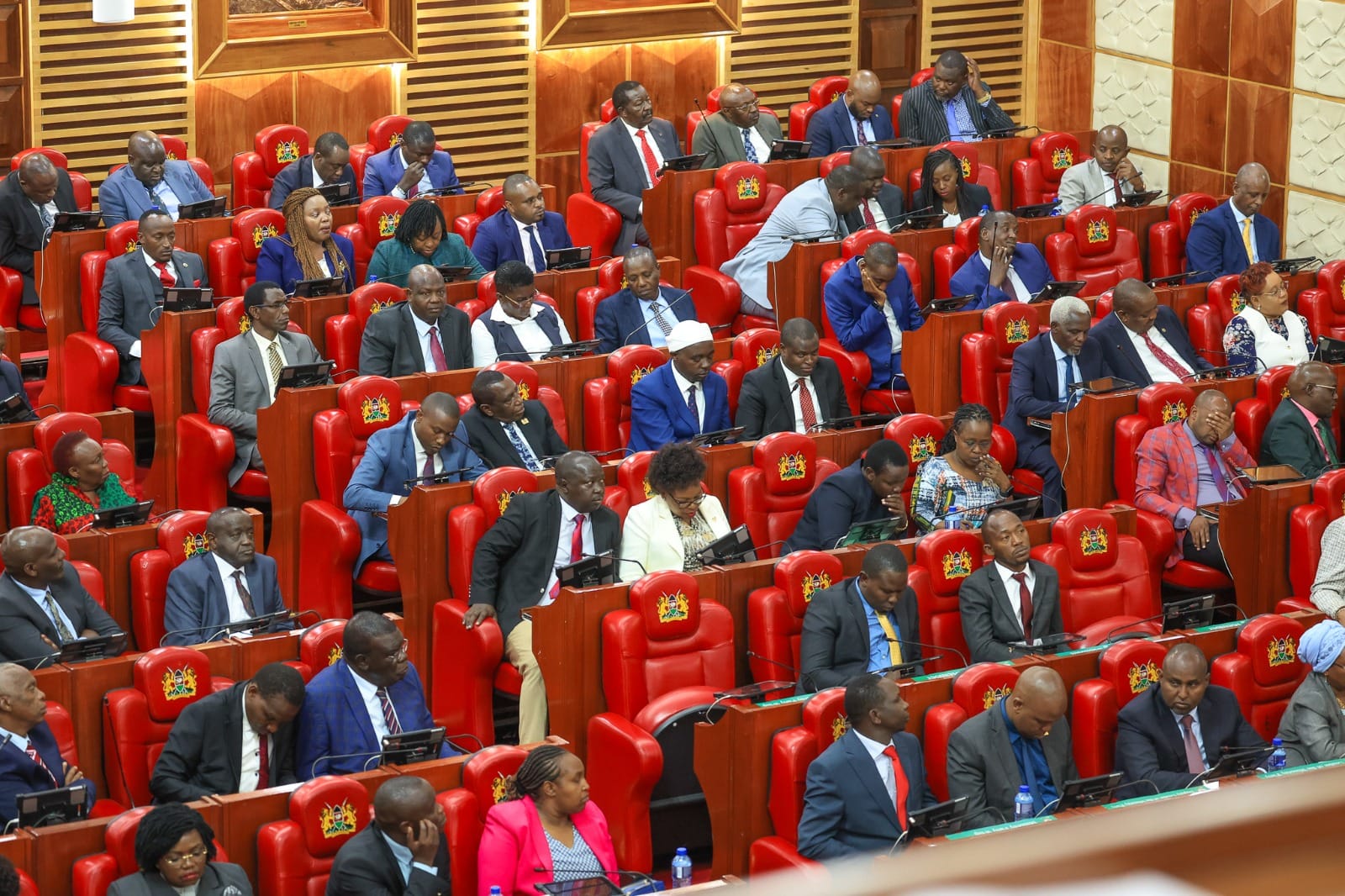

Kuria East MP Kemero Maisori recently ignited debate with a revelation that he’ll table a Bill in Parliament to amend the Constitution to create five new counties.

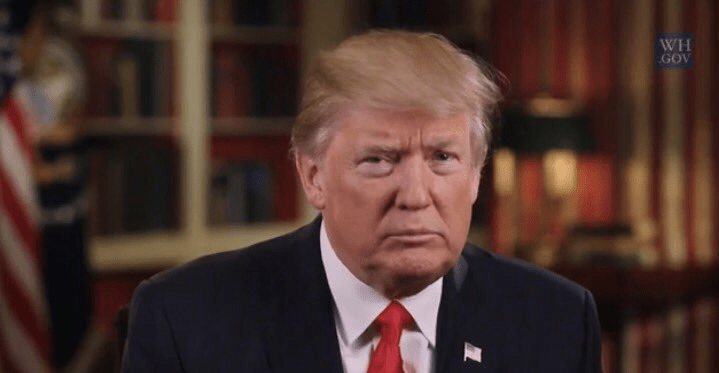

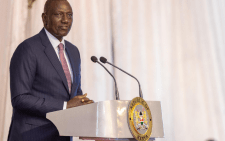

The proposed counties are East Pokot, Kuria, Mt Elgon, Mwingi and Teso. Maisori’s Bill is not an official UDA Bill but is a follow-up to a promise President William Ruto made to a delegation of Abakuria that visited him at his Transmara home earlier in the year. Ruto reportedly declared support for a Kuria county, hived from Migori.

Maisori’s move has caused excited chatter with some critics claiming it will increase the burden on the taxpayer. Others have labelled it tribal while others have dismissed it as unnecessary because the current counties provide opportunities for representation and growth for all.

However, no critic has explained how affected marginalised, oppressed and discriminated minorities can rise to leadership in a country as tribal as Kenya, in which voting is ethnic; “strongholds” are tribal and positions are shared on ethnic demographic weight. Presently, there are too many hypocritical deniers; people who believe that although Kenya is a declared non-tribal state, no one should speak in tribal terms yet ethnicity defines our identity, culture and history.

The deniers mobilise their tribesmen and women to vote for one of their own, to protect tribally-earned positions and demand a share of government because they come from certain weighty ethnic demographics.

Although the existing 47 counties have largely been accepted, their impracticality and ethnicity have been obfuscated by excitement over devolution. This has enabled governors to freely loot their counties because, as we realised in Migori, the dominant ethnic majority is not ready to cede power to a minority. The result has been that there has been markedly lower development in counties in which the threat of losing power to a competing ethnicity exists.

Secondly, the people were not heard during the creation of the counties and their boundaries in 2010. The decision to create these counties was arbitrary – when the drafters of the Constitution got stuck on how to create and demarcate the new counties, a delegate suggested they use districts gazetted in 1992 as counties. Kenya’s districts were tribal, which made the resulting counties tribal. There was no public discourse on the boundaries, rationale or viability. Agitation for counties being condemned as tribal should therefore not be a reason to deny the Abakuria, Akamba, Iteso, Pokot and Sabaot their own counties.

If these new counties are created, they would join the existing counties, all of which, with the exception of Nairobi, are tribal; Kisii is tribal and so named; Meru is tribal and so named, etc.

The supreme law does not create mechanisms for negotiation or power sharing in the country. In counties where one ethnic group is dominant, like in Migori, there is a sense of entitlement from the dominant group, who believe that the position of governor is their right.

This results in “tokenism”, which occurs when a member of a dominant ethnic group takes actions that appear to be affirmative or inclusive but which actions are intended to meet constitutional obligations or to silence dissent and have no impact in power-sharing. In Migori, the Abakuria have been appointed to fringe departments as CECMs and out of 21 Chief Officers, only three are Kuria while the other 18 are Luo.

Those citing cost as a factor must provide justification for the retention of small, low-population “special” constituencies for majority ethnicities.

Similarly, there can be “Special Counties” that protect the interests of threatened and oppressed minorities created as affirmative action.

— The writer is a former Migori CECM for Education, Youth and Culture