Burden on citizens to foster ideals of Constitution

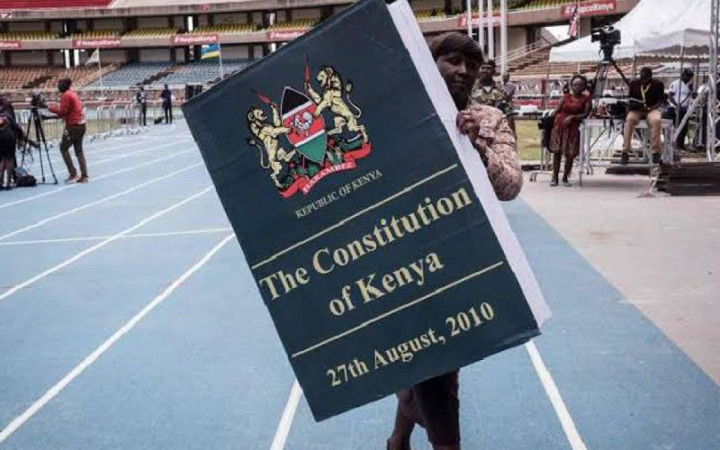

In the context of the Constitution, “sovereign power” refers to the ultimate authority and right to govern which, according to Article 1, belongs to the people of Kenya and must be exercised only in accordance with the supreme law. This power can be exercised directly by the people or through their democratically elected representatives.

The Constitution empowers citizens to delegate their sovereign power to specific State organs, including Parliament and the 47 county legislative assemblies; the national and county executives; and the Judiciary and independent tribunals. Put differently, both citizens and the governments they elect at the two levels have a shared responsibility to ensure that the Constitution is implemented to the letter and ideals realised.

The preamble of the Constitution provides the most lucid summary of the supreme law of the land, creating a situation in which Kenyans are “proud of our ethnic, cultural and religious diversity, and determined to live in peace and unity as one indivisible sovereign nation”, going further to state that as a people we are “respectful of the environment, which is our heritage, and (are) determined to sustain it for the benefit of future generations”.

It then reaffirms our “commitment to nurturing and protecting the well-being of the individual, the family, communities and the nation”, while at the same time “recognising the aspirations of all Kenyans for a government based on the essential values of human rights, equality, freedom, democracy, social justice and the rule of law”, concluding that in “exercising our sovereign and inalienable right to determine the form of governance of our country, and having participated fully in the making of this Constitution; we adopt, enact and give this Constitution to ourselves and to our future generations”.

But why is this clarity important? During debate on the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), opponents of proposed changes advanced the argument that rather than seek to change the Constitution, the government and its allies in the opposition should endeavour to implement it. According to this school of thought, the authority to implement the Constitution vests solely on those in leadership, hence the chorus to implement the Constitution instead of hatching a plot to amend sections of it.

In the 2022 elections that followed the botched attempt to amend the Constitution, candidate William Ruto and his Kenya Kwanza brigade rode on the crest of their opposition to the BBI, characterising it as a scheme by President Uhuru Kenyatta to favour veteran opposition leader and presidential hopeful Raila Odinga.

A flashback will suffice to put issues into context. In the wake of the 2017 annulment of the presidential vote and subsequent re-run, Kenyatta mandated the formation of a task force on 31 May 2018 to suggest constitutional, policy and legislative remedies in which nine nine broad issues they had come up with – lack of national ethos; persistent ethnic antagonism and competition for political power; exercise of rights with a sense of responsibilities; shared prosperity; divisive elections; safety and security; devolution; corruption; and inclusivity – would be addressed.

My interpretation is that the intention of the BBI proponents was to draw public attention that despite overwhelmingly giving ourselves a new Constitution, complete with a code of practice to guide us on how to conduct ourselves and public affairs, there are yawning gaps in the practice of the supreme law, gaps not only exhibited by the leadership but by citizens as well.

Since then, President Ruto, who vehemently opposed the BBI in 2021, has admitted that there are indeed pertinent issues that, if addressed, could help alleviate some of the governance challenges facing us as a people.

While some have opposed the nine-point agenda that Ruto and Raila have raised, dismissing them as unnecessary, with claims they are already addressed in the Constitution, the supreme law vests as much if not more responsibility on citizens to ensure that its ideals are realised.

— The writer is the Executive Director of the Kenya National Civil Society Centre, and Chairperson of the Horn of Africa Civil Society Forum; suba_churchill@yahoo.com