Why women now go for sperm donors, not husbands

The procedure is becoming popular in a nation that has no laws about it, which has created ethical and legal concerns

Days after he posted photos of himself and his daughter on Facebook three years ago, Nigel* received an unexpected call. A classmate from college called requesting him to be her sperm donor.

“It took me by surprise. Apart from being classmates we did not know each other well,” says the single father of one.

His classmate wanted to conceive and raise a child by herself and the photo of Nigel’s daughter on Facebook had convinced her he was the right match. But the young lawyer turned down the request.

The prospect of fathering a child he would not raise was inconceivable for him. Not even the assurance that she would keep his identity hidden from the child would put his mind at ease.

Nigel’s classmate is in a growing pool of women and couples in Kenya opting to have children through sperm donation.

Couples consider sperm donation due to health conditions that hinder them from conceiving on their own.

“This could range from a man being incapable of producing normal and enough sperms to fertilise an egg to having a genetic condition they may not wish to pass to their offspring,” says Dr Alfred Murage, Consultant Gynecologist and Fertility Specialist, Harley Street Fertility Centre.

Likewise, there are single women attempting to start a family without being physically or romantically involved with a man.

In both scenarios, couples or women opt to use sperms produced by a sperm donor. This could be someone known to them including a friend or relative or an anonymous donor.

Though there is no law to regulate it, sperm donation is a medical procedure practised in Kenya and goes hand in hand with modern infertility treatment through Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) such as In vitro fertilisation (IVF) and Intrauterine Insemination (IUI). Fertility clinics that offer sperm donation services follow general guidelines on health procedures.

“Clinics prescribe to certain ethical guidelines. Our practice for instance is based on UK regulations where IVF procedure began. Principles by the Kenya Medical Board also guide our practice,” says Murage.

So why is the need for sperm donation increasing? Experts say couples are struggling with infertility, especially in Africa where most are under a lot of pressure to have children. S

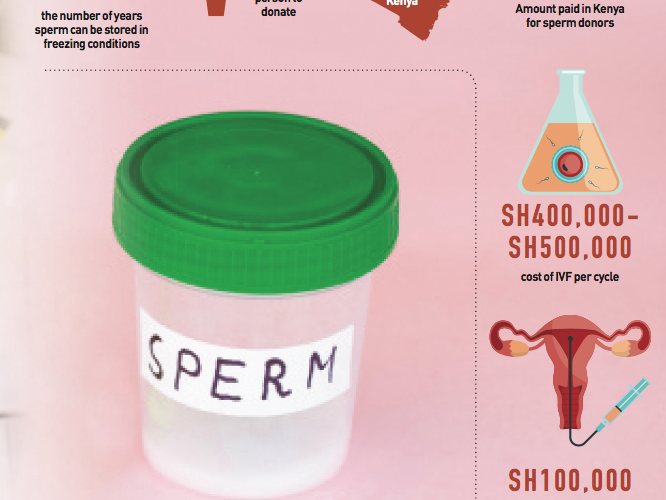

ocietal beliefs that attach completeness of a family to having children also push couples to unimaginable lengths. Opting for sperm donation is a viable option for couples who need assistance having children and who can afford the costly procedures. On average, it costs Sh500,000 to undergo IVF and Sh100,000 for IUI in Kenya.

List of standards

Donating sperms is done voluntarily by individuals who fulfill certain standards. Murage says ideally, sperm donors in Kenya should be aged 25-40 years.

This age bracket ensures donors are old enough to understand the enormity of their decision, but also reasonably young enough to have healthy sperms. Potential donors also undergo several tests to ensure they are not infected with any infectious diseases such as HIV/Aids, hepatitis or syphilis.

Ideally, a potential donor ought to declare if there is any hereditary disease in their family to avoid the risk of passing it on. Their sperms are then tested to ensure they are normal and capable of causing a pregnancy.

“If someone passes all these three steps, we get information about their social circumstances, which include their job, level of education. Factors such as drug abuse and criminal records can warrant a donor to be disqualified,” adds Murage.

After meeting the set requirements, anonymous donors are put on a waiting list until a suitable recipient comes along. “Sperm recipients specify the age group, physical and social attributes such as the career of the donor they would want. Our work is to match the two,” says Murage.

While some fertility clinics own banks to store the sperm others don’t. For those that have banks, sperm is stored in freezing conditions with liquid nitrogen and can remain in good condition for up-to 20 years.

As a precautionary measure, stored sperm is tested three months after donation to ensure no illness such as HIV might have been in its incubation stage. Both donors and recipients sign consent forms to seal sperm donation process. “Consent forms are legally recognised documents. Issues such as the level of involvement of the donor in a child’s life, especially in the case of non-anonymous donations are outlined in the form,” says Murage.

Low acceptance

The trend in sperm donation in Kenya is that as the demand for it is increasing so is the number of people willing to donate. Murage says most sperm donors are young university students who show up at clinics volunteering to donate.

Donors receive a stipend of Sh5,000 to cater for their expenses and not as payment since it is an act of altruism. He, however, notes awareness and acceptance of the procedure is still low.

“Issues regarding infertility are highly stigmatised in our society. People are yet to understand why a person would require donated sperms, therefore more education needs to be done,” he says.

World over, the first successful pregnancy with donor sperms was reported in the early 19th Century in New York, USA. The process, however, gained popularity and became commercialised in the 1970’s.

In 2005, the United Kingdom, where the practice is common, resolved to remove anonymity of sperm donors allowing children conceived through donated sperms to trace their biological fathers once they turn 18. The move has led to severe sperm shortage in UK forcing the country to resort to importing from US and European Union countries.

Posthumous donation

In a recently published analysis in the Journal of Medical Ethics, UK suggests it should be morally permissible to have post death sperm donations.

The justification is that sperm donation should be treated the same way as other body organs, which can be donated once a person dies.

Scientific evidence shows sperm can be collected after death through electrical stimulation of the Prostate gland or surgery. Sperms can be collected even 48 hours after death and result to viable pregnancies and healthy children.

Such a move, Murage says, poses several hurdles including getting the consent of the donor’s family.

For non-anonymous donations, both donors and recipients fill consent forms that specify the involvement of the donor. The question is are recipients going to accept sperms taken from a dead person?” he poses.

Murage opines that Kenya is not close to embracing posthumous sperm donation, considering there are no clear laws to guide the practice. Besides, unlike UK, the country does not have a national database on sperm donors where proper records are kept.