Banks face scrutiny over costly loans as MPs call for lower interest rates

The massive profits raked in by digital lending platforms, which charge an average of seven per cent interest upfront yet expecting full repayment within a fixed period, have placed lenders under scrutiny.

Lawmakers argue that this structure results in exorbitant annualised interest rates, burdening consumers and stifling economic growth.

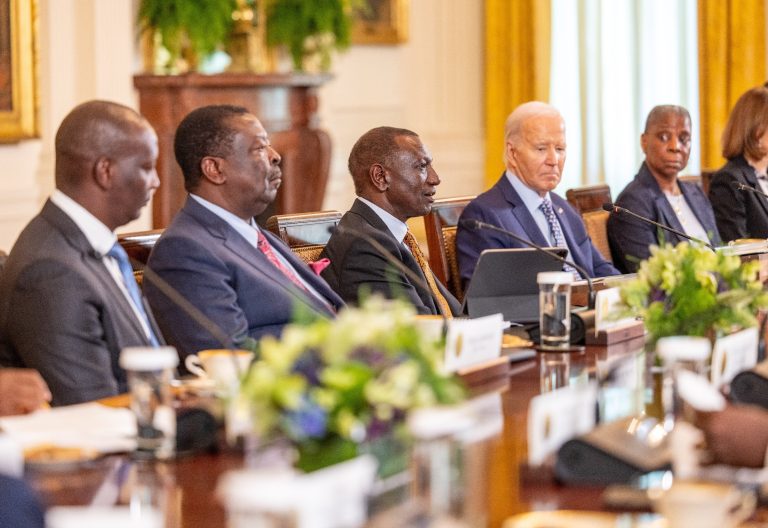

National Assembly Finance Committee chair Kuria Kimani strongly criticised banks for failing to lower their rates, calling the practice a form of consumer exploitation.

“The interest rate is too high for an ordinary Kenyan, and that’s how you have been recording billions in profits. Interest should accrue towards the end of the given period, not as an upfront charge. This setup appears to impose double interest on loans,” he remarked, pressing the Kenya Bankers Association (KBA) for answers.

The total assets within the banking system surged to Sh7.7 trillion, marking a 17.6 per cent annual increase. This expansion was primarily driven by large banks, which recorded a 21.8 per cent growth in assets.

Growth in assets was accompanied by a 15.1 per cent increase in banking system deposits, surpassing the 13.1 per cent growth recorded in 2022. Industry data shows that this uptick was largely attributed to the proliferation of mobile and online banking platforms, which enhanced accessibility and convenience for customers.

Additional non-interest charges

In terms of profitability, the listed banks recorded a 23.5 per cent weighted average return on average equity (ROaE) in the third quarter of 2024.

Kimani also raised concerns over additional non-interest charges, such as processing and withdrawal fees, which further reduce the actual loan amount received by borrowers.

He noted that high costs have made bank loans inaccessible for small businesses, limiting their growth and constraining money supply within the economy.

Furthermore, he accused commercial banks of disregarding the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) directive to lower rates, pointing out that despite some reductions, many banks still maintain interest rates above CBK’s benchmark rate of 10.75 percent.

“Banks are clearly in contravention of the CBR and the Constitution by setting interest rates higher than the CBK rate more than a month later,” he added.

In response, KBA chief executive Raymond Molenje defended the banks, stating that each institution operates under its own risk management framework, leading to variations in interest rates. However, he maintained that banks have complied by reducing rates by an average of three per cent since November.

Call for uniform framework

“It’s actually at the individual bank level. CBK has different frameworks, and if you apply them to some banks, their interest rates would actually go up. What we need is a uniform, transparent framework across all banks to ensure compliance,” he stated.

Molenje further pointed out a dilemma: some banks chose not to raise interest rates even when CBK increased the lending rate, opting instead to cushion consumers and remain competitive. As rates decline, these banks are struggling to adjust. He assured the committee that by the end of the month, KBA would release a report detailing how banks have responded to the interest rate cuts.

Kimani noted that despite CBK’s stern warnings, some commercial banks continue charging rates as high as 19 per cent, depending on the loan category. He emphasized the need for a standardised risk-based pricing model, warning that failure to provide affordable credit would cripple the private sector. “This is our currency, and if we don’t find a way to ensure access to credit for the private sector and MSMEs, we risk collapsing those industries,” he warned.

Molenje acknowledged the challenge banks face in lowering rates, particularly since the government borrows from them at higher rates with guaranteed repayment. He said while banks apply risk-based pricing, there is an urgent need for a policy framework guiding government domestic borrowing to accommodate both public and private sector needs.

“Our appeal as an industry is for a reassessment of government borrowing policies. Perhaps we can replicate what happened in 2002 when the government stopped crowding out the private sector. A similar approach could help bring down the cost of borrowing,” he urged.

On the subject of interest income, Molenje revealed that 60 per cent of banks’ interest earnings come from private sector loans, while 40 per cent are derived from government securities.

“Most basic loans are active loans, making up around 50 per cent of the total. This means that out of the entire interest income portfolio, 40 percent comes from government lending, 30 per cent from basic secure loans,” he explained.