How Shofco is winning war on COVID-19 in Kenyan slums

They are not doctors, nurses or medics of any sort yet they go about doling advice on the importance of handwashing, mask wearing, hand sanitisers and social distancing.

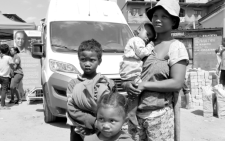

Poorly paid or not at all, this group of mostly women community health volunteers have for years given out health services to families living in Nairobi slums who lack formal support.

When Coronavirus struck, they became a key cog in the fight against the pandemic.

Mary Akello is one such woman. For decades, the 60-year-old has helped women in her neighbourhood in Nairobi’s Kawangware slums to manage chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer and HIV/AIDS.

This has been her routine since she was 30 years old. Her reward? “I am motivated to save lives,” she told this writer during an interview at her one-roomed house on August 29.

But even with all her experience, COVID-19 was a totally different monster for Akello and to tackle it head on, she needed different tactics.

“People here believed Coronavirus is a disease for the rich. Those who travel by plane and so they thought it would never catch them. Until some positive cases were reported here, I had a difficult time convincing them,” Akello recalls on her first experience educating her community about the disease when it first landed in Kenya in March.

To get the message across, Akello had to go house to house through Kawangware’s maze of narrow lanes, risking her life to teach residents the dangers of COVID-19, how to wash hands or don a mask while patiently answering their questions.

But none of this would have been possible without the help of SHOFCO, which stands for Shining Hope for Communities.

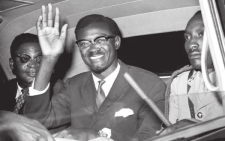

Founded in 2004 by Kenyan philanthropist Kennedy Odede as a way of giving back to society after overcoming a tough childhood from the informal settlement of Kibera, Kenya and Africa’s largest slum, SHOFCO is a grassroots movement that catalyses large-scale transformation in urban slums by providing critical services for all, community advocacy platforms, education and leadership development for women and girls.

For Akello, SHOFCO was Godsend. “In a community where two meals a day is a luxury, buying masks and sanitisers is not a priority. Hand washing with soap all the time is also impossible since we do not have proper running water,” says Akello.

She goes on: “But SOFCO came through for us in a big way. They donated masks, sanitisers, soap and installed several hand washing stations in this slum. That made our work easier since when we move door to door, we go with these items to give residents as we educate them. They buy the message easily because we are able to demonstrate firsthand how to use the items.”

Akello is not alone, there are hundreds of such volunteers in the five wards within Dogoretti North Constituency where, Kawangware is situated, with each volunteer assigned 100 households.

SHOFCO has a presence in 14 urban slums in Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu and since March, they have organised several training opportunities for the volunteers through partnerships with the Ministry of Health and other Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs).

As Akello and her peers combat COVID-19 in Kawangware, Julia Njoki is leading the fight against the virus in Mathare, another informal settlement with a population of close to 500,000 people.

Njoki, just like Akello, is thankful that SHOFCO has a presence in Mathare. “They serve all 28 villages here and the trust between SHOFCO and the community is at an all-time high since this pandemic landed here,” Njoki shares to this writer at her home on September 5.

“Local administrators like Chiefs have trust issues. They take our details, promise government relief food or cash but it never reaches the community. When COVID-19 came, residents demanded that whatever is being donated either from the state or other aid agencies must come through SHOFCO because they do not discriminate,” adds Njoki.

Indeed, SHOFCO have been of great help, installing 301 handwashing stations at entry points in each of the 14 slums they work in, brought in tens of millions of litres of free water, and with the help of other partners, sourced over 400,000 bars of soaps for distribution.

The organisation has also reached close to 2 million households in slums with their free masks and sanitisers, making the fight against the pandemic easy.

“Many here thought the disease is a joke but after seeing what it can do to people’s lives, they had to take precaution,” says Irene Were, who heads the SHOFCO Urban Network department in Mathare.

At the start of the war in March and April, Kibera, Kawangware and Mathare had been giving the government a headache on how to combat new cases and avoid the spread of the highly infectious disease due to the congested nature of slums, but SHOCO, through the help of the volunteers who know the areas like the palm of their hands, helped the state contain the situation.

But why wouldn’t SHOFCO just concentrate on their core mandate and let the government deal with COVID-19?

“We had to stay true to our motto of shining hope to the community. You know even here at SHOCO, most of our employees come from the slums and we have to keep hope alive by doing what is right not just to them but the entire community,” adds Irene.

For Odede, it is perhaps satisfying seeing that the slum community, especially his beloved Kibera, is not in the news for all the wrong reasons as it has been predicated.

“The coronavirus messaging was so westernised; it did not work for people who live in informal settlements. We needed a radically different approach. Information had to come from people they trust, either religious leaders or local people on the ground. That is how we managed to contain the virus,” reveals Odede.

With the hygienic measures in place and working, Odede went an extra mile, including food and cash relief to the programme, a big boost since most of these families had either lost jobs or had their businesses suffering.

“Every action we take is meant to save lives, so whatever we get we make sure it reaches them first. We also get feedback from the community and this encourages us to push even harder,” adds Odede.

For Njoki and Akello, the relief food and cash programme has been a shot in the arm not just to the community but to them as well.

“I do not have a job, so paying my rent and buying food is difficult. When the relief food and cash comes, we also get something small and it motivates us more,” says Akello.

“This food and money has saved people from committing suicide in Mathare, says Njoki, adding: “Most people here do menial jobs and when the pandemic struck, they lost them. Because they live from hand to mouth, it was difficult to get food and pay rent. Escaping to the village was not possible due the cessation of movement in and out of Nairobi that was in place from March to July and so depression set in. This is how they commit suicide or domestic violence and so the relief food and cash helped a great deal.”

Njoki and Akello’s sentiments are echoed in Kibera, Mukuru, Soweto and Kamukunji, some of the other slums in Nairobi, where health volunteers are battling the virus in their communities.

SHOFCO is providing the ammunition and without fanfare, these essential foot soldiers are slowly winning the war against COVID-19.