Ruto gift: Catholic Church can afford to be snotty

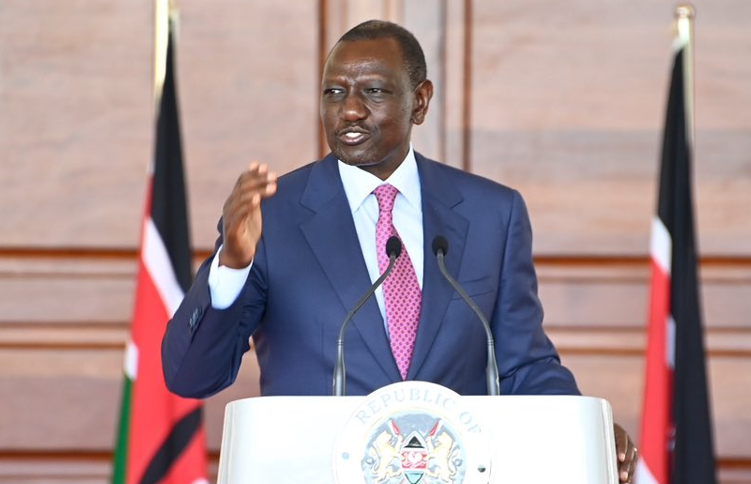

Church watchers were stunned when President William Ruto’s donation of over Sh5 million to a Nairobi parish was summarily rejected last week. Nairobi Archbishop Philip Anyolo explained that the gift had violated church directives and a proposed law on fundraising that’s under consideration in Parliament.

In an unusually articulate statement, Anyolo went straight to the point: “The Church is called to uphold integrity by refusing contributions that may inadvertently compromise its independence or facilitate unjust enrichment. Political leaders are urged to demonstrate ethical leadership by addressing the pressing issues raised by the Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops.”

Ruto’s donation was substantial by any standards – about Sh2.5 million paid up front, with promises of more to come, including money for a parish rectory, a choir and a bus.

No needy church organisation would turn down such largess. I hear that so much money is collected in impromptu fundraisers at churches on weekends – often with the help of politicians – that clerics ask local police to help guard it or carry it to wherever it can be stored safely before it’s banked.

Undeterred by the humiliation, Ruto responded with defiance, saying he would continue donating to churches. He claimed to be a product of giving and that his faith calls upon him to give back. He knows, and you can bet, that his money and other gifts won’t fail to find takers.

The Catholic Church, meanwhile, can afford to be snotty, as it’s presumed to be an immensely wealthy institution. What Anyolo’s unexpected gesture suggested was that Catholics don’t need the President’s generosity.

But just how wealthy is the Catholic Church in Kenya, and why do we know so little about its finances?

The scale of the Church’s potential wealth is breathtaking. Speculation runs rampant about holdings worth trillions of shillings in cash and property.

But attempting to substantiate these claims is a fool’s errand. This week, a local journalist tried – and failed – to compile a comprehensive assessment of the Church’s assets, and ended up with little more than a catalogue of known properties and no meaningful valuation.

The Church’s asset portfolio is impressively diverse. From grand cathedrals and sprawling educational institutions to cutting-edge hospitals, vast agricultural lands and commercial properties, the Catholic Church touches almost every aspect of Kenyan society.

But this very omnipresence is exactly why tracking its financial footprint is almost impossible.

There are several reasons for this lack of transparency. The Church’s organisational structure is a maze of financial independence. Each diocese operates autonomously, creating a decentralised system where individual parishes manage their own accounts. Religious orders complicate the picture further by maintaining separate asset controls.

Kenyan law provides little help. The Church is not legally required to publish comprehensive financial statements (though a proposed religious organisations law could shed more light on the finances of these groups). Most dioceses seem determined to maintain a veil of financial privacy, and regulatory bodies appear either unable or unwilling to penetrate this carefully built financial fortress.

History adds another layer of intrigue. Many Church properties trace their origins to the colonial era (a disputed multi-acre tract claimed by the Church and locals in Nyeri is a good example), with land ownership histories so complicated they could challenge even the most dogged forensic accountant.

To better understand the scale of the Catholic Church’s wealth would require access to financial reports, but these documents are not readily shared with the public. Land registry records would offer only fragmented insights, while annual reports from specific Catholic institutions would provide only glimpses of the true picture.

This lack of transparency isn’t a Kenyan anomaly. It reflects a global pattern where religious institutions (not just the Catholic Church) often operate with minimal public financial oversight. The Catholic Church represents one of the most sophisticated examples of financial guardedness.

— The writer is a Sub-Editor with People Daily-