The lonely struggle of living with dyslexia

Martin Gichuki, 27 discovered he had learning difficulties at a tender age, but did not know what exactly was wrong until he was in Class Three and was forced to repeat.

“This problem manifested in some of my cousins and it became a family concern. Then one day, my aunt came across an article in a magazine that described the common traits of a dyslexic person. This revelation led to sleepless nights of research about the condition and they finally found out what ailing him and some of his family members. It was concluded that I acquired dyslexia through the family tree, because it is hereditary,” says Martin.

Born last in a family of three children, Martin says his siblings did not have any difficulties in school.

“I was nine years old when I first learnt about the term dyslexia, and what it really meant. I went through so much tutoring. I was mostly punished for performing poorly in both English and Kiswahili. This was because I performed better in mathematics and science and the teachers thought I lacked interest in languages, to which I was denied an opportunity to participate in co-curricular activities like my fellow classmates. As a result, I developed a self-defensive mechanism against the school environment and my parents would be called to school to address my changed behaviour,” he says.

Due to his learning challenges and behavioural problems, Martin moved from one school to another, including New Highlight School in Dagoretti where he studied from Class One to Class Six, St Lwanga in Narumoro for Class Seven and sat his Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) at Shalom Junior Academy in Thogoto in Kikuyu, Kiambu County in 2009 where he attained 352 marks out of the possible 500 marks. He then went to Njabini High School where he sat for his Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) and attained a C+.

Spelling mistakes

He graduated from Jomo Kenyatta University of Science and Technology (JKUAT) with a bachelor’s degree in Business Information Technology.

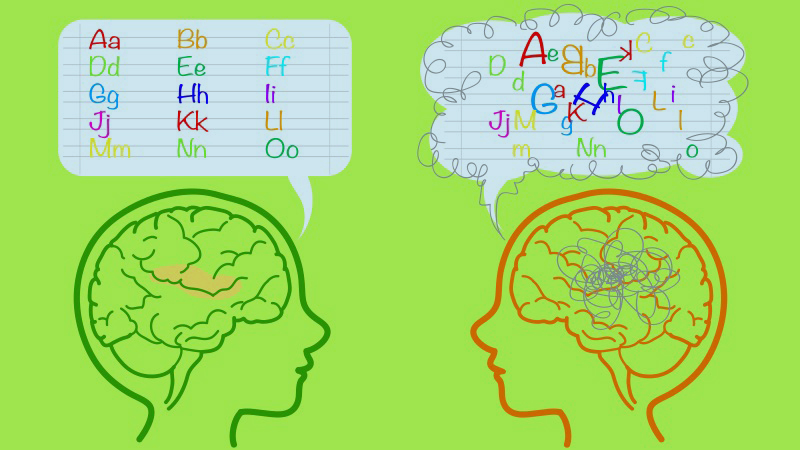

When it came to writing essays, Martin had a high number of spelling mistakes, poor handwriting and mixing up the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’. He also experienced difficulties in reading out aloud and read at a very slow pace. “Dictation was quite a task and I mostly did substitution of words that sounded similar and wrote words as they sounded,” Martin says.

At some point, his parents opened up to his teachers about his condition, but this would only worsen the situation.

He offers: “The teachers had no knowledge of dyslexia and thought that it was an excuse for my bad performance in their subjects. In most cases, I preferred being called a slow learner than explaining to them that I am dyslexic. Since the condition cannot be seen, it’s quite difficult to explain it.”

The learning challenges affected other aspects of his life, such as his self-esteem. He also had difficulties expressing himself in public. He hated doing exams and their outcome. Knowing that what was troubling him had a name was a sigh of relief.

He opines: “While in Class Six, I started training with Audiblox, a multisensory cognitive enhancement programme, effective for a variety of learning difficulties including dyslexia. I also did remedial classes every morning and evening before and after school. Audiblox helped me to improve my memory in learning new and difficult words. And since I was good at maths and science, it helped me improve my average performance.”

Today, Martin who works at Majorel Kenya, an outsourcing and offshoring consulting firm as a Customer Support Representative has accepted and lives with the condition positively.

“Knowing other people living with dyslexia who have succeeded in life gives me the confidence to push on. Having graduated from the university is proof that I overcame dyslexia. Being dyslexic has helped me become good in problem identification and solving, fast in changing ideas and thinking in picture form. I have to visualise everything I think about,” he shares.

Creating awareness

At work, due to his difficulties with words, he uses reading and language app, such as Grammarly and auto-correction while typing. He uses simple english and substitutes synonyms that are simpler to spell.

Martin strives to make an impact in the lives of other individuals who have dyslexia by creating awareness and sharing his story as an encouragement.

“After campus, I volunteered at Rare Gem Talent School where I taught children with dyslexia who felt unappreciated for not performing well in school by encouraging and motivating them. Now as a parent, I major on what my children can do well and support them in their weak areas,” he says.

“My wish is that the government can give more support to children with learning difficulties by introducing special needs and learning difficulties as a unit in teachers’ colleges. This would be of great help to all students with or without learning difficulties, because a teacher will understand their strengths and support them to improve rather than victimising a child for a condition they have no control over. Dyslexic people are very talented hence they need to be encouraged rather than be judged or shunned,” he adds.

He plans to open a dyslexia youth group in Kenya, which will serve as a platform for dyslexic youths to share ideas and their life experiences, and mostly to nurture their talents.

Nancy Munyi, a special needs teacher and a professional assessor describes dyslexia as a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin and is characterised by difficulties with accurate and fluent word recognition, poor spelling and decoding abilities.

“These difficulties typically result from a deficit in phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and provision of effective classroom instruction,” says Nancy who is also the founder and director of Rare Gem Talent School which is a special needs school for children with dyslexia and the co-founder of Dyslexia Organisation, Kenya (DOK).

Before she became an expert on matters dyslexia, Nancy was a parent of a son who could not read at a young age. His struggles when reading were a real pain to him and everyone in the family.

“From an early age, he showed no reason of anyone getting concerned that he would face any challenge at school. He was lucky that I was his first academic teacher and mother. I got concerned that other students in my class were learning to read effortlesslessly whereas my own son was not just getting it, but also giving all types of excuses not to go to school because he knew I would teach reading. At first, I thought he was just not serious with his class work, and that he would improve if I became hard on him. But things got worse, because he started becoming truant. His siblings thought that he would learn to read with time as he grew older. I had two other students, such as him in class. It was a real concern. Checking with my colleagues, they thought that my son was okay because he could do mathematics well. But I knew there was more than that,” Nancy explains.

No test to diagnose dyslexia

She embarked on research, questioning, and discussing with other educationists and parents and found out that her son had dyslexia.

“There is no single test that can diagnose dyslexia. However, a number of factors, such as the child’s developmental issues, educational and medical history, vision and hearing, psychological evaluation and reading and academic skills are considered,” Nancy says.

She shares: “Parents and care givers have a key role to play where dyslexia is concerned. If a parent suspects that their child is struggling, waiting a little while is not a solution. They should take their children for assessment. Early identification is the key. People with dyslexia are outside the box thinkers. They should be given an opportunity to be critical thinkers. Children with dyslexia are supposed to learn in the mainstream classes, but should be given individualised support.”

The expert further notes that dyslexia has not been given the support it requires.

“Teachers have not been trained to identify and support dyslexia students. Parents are still thinking that their children are refusing to work hard. Others say that their children have been bewitched while others blame the teachers for not giving children a good foundation in entry classes. Teachers on the other hand blame parents for being too busy to support their children with academic issues.

This October, let us paint the country red with dyslexia awareness. I am challenging everyone to learn as much as possible about dyslexia. It is the only way we can reduce stigma on those not able to read at grade level,” Nancy says in ending.