Why Kenyan youth should engage in political processes

Kenya has made significant gains in its social economic aspects, but not so much in political socialisation.

Our politics have been dominated and left to very few people for long, who know only one narrative – ethnic political mobilisation.

As has been the norm since Kenya ushered in multiparty democracy in early 90s and every time an election approaches, political bickering has moved an octane higher.

At the moment, it has literally become an overarching war of two political sides, with one supporting the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI); pushing for constitution amendments while the other opposing it.

Around 2002, Kenya witnessed a different political ball game, where a wind of change saw politicians, non-governmental organisations, churches, labour unions, and women organisations all came together and successfully removed Kanu from power. Kenyans were even ranked as most optimistic people in the world.

However, instead of consolidating the gains made by defining politics of inclusive governance, the country was sharply divided only after a few months after the election victory as politics of self-interest set in.

The divisions would take shape in the years that followed culminating in the government’s loss of referendum on the mutilated draft constitution, which almost pushed the country into a precipice of ethnic violence after 2007 post-election violence.

But one of the most unfortunate things that happened was the fate of civil society that went into a deep slumber after the 2002 elections was won by an opposition it had helped craft.

Some of its leading luminaries were accommodated in government and with a presumably responsive government in place, civil society activities were as well scaled-down.

In the same vein, donor financing shrank as sizeable resources would now go to the ‘responsive’ state.

Since then, Kenya’s politics have been defined and perfected through ethnicity perpetuated through regional tribal kingpins.

This situation is even worse since there is no formidable opposition after the handshake of March 2018.

Parliament has significantly been twisted and compromised to effectively check the executive excesses.

Unfortunately, there have been several attempts to disable the judiciary by reducing its funding and disobeying its orders.

However, all is not lost if youth can make a decisive move to engage in politics constructively since they have numbers – the greatest political asset.

They are also the greatest casualty of bad governance since dysfunctional leadership will leave them jobless and without a means to a livelihood for another electoral cycle-as it has happened.

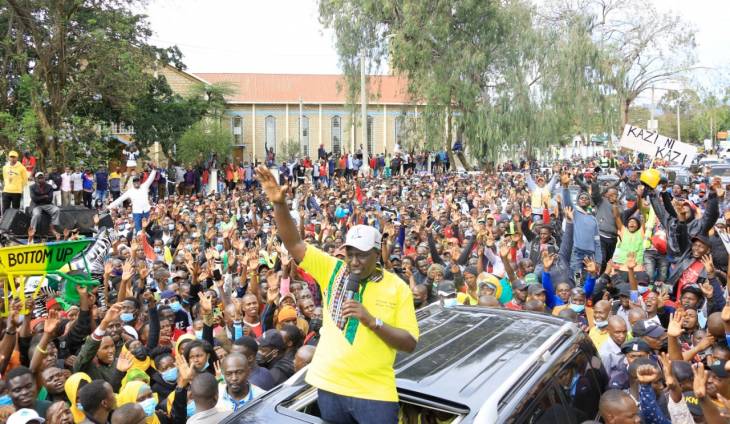

As political parties start seeking coalitions to secure positions in government after the 2022 general election, youth can leverage on social media platforms, today’s most effective tool of mobilisation and create a political constituency of its own – an electoral vehicle.

Assessments show if well-organised, youth can change Kenya’s politics. It is the lack of this organisation that has seen a number of young people already in elective and appointive positions vulnerable to politics of survival and patronage.

If the youth can be made to believe that they can dictate their destiny, the country could embark on a trajectory towards good governance.

With 2022 elections not very far away and campaigns already underway, the place and role of the youth in shaping the outcome is very critical.

Kenyans aged between 15 and 34 years form about 36 per cent of the total population.

Those below age 34 constitute about 80 percent of the population. Out of the 14 million registered party members in Kenya, a paltry 27 per cent constitute youth.

The Youth Congress, a local NGO mobilising and supporting young people in marginalised areas on socio-economic and empowerment programmes, launched Youth Leagues in each of the 47 counties, to rally and inform young people on active participation in political processes.

More of such initiatives are needed and must be supported by non-state actors such as the churches, free press and other civil society so that they can be insulated from capture by politics of the day. — The writer is the author of Conversations about the Youth in Kenya. raphojuma@hotmail.com