Wanini Kireri: A dreamer living her big dreams…

By Isam Latoti

One morning in November 2009, a tall man with a greying beard and receding hairline walked through the gates of Shimo La Tewa Maximum Security Prison in Mombasa. Dressed in a flannel grey coat and a white T-shirt, he was ushered in to meet Wanini Kireri, then a Senior Superintendent of Prison, in charge of the facility housing over 2,400 inmates.

She took him around and later bid him goodbye. The next day, she received an avalanche of congratulatory messages and calls with people hailing her for hosting one of the biggest names in Hollywood.

“All I knew was he was Nicolas Cage, the UN Goodwill Ambassador on Drugs and Crime. He came to see the transformation that was in the prison,” says Wanini, now a Senior Assistant Commissioner General of Prisons and the first female commandant of Prison Staff Training College in Kenya.

“I was not into movies otherwise I would have known he was movie star,” she says with a soft laugh.

That anyone can spend over an hour with a Hollywood legend and never make a fuss about it might sound incredible. That’s the modesty that defines the most decorated Kenyan prison female officer.

Big nurturer

Standing close to six-feet tall with her signature crown of short ginger hair, Wanini stands out without trying. Her voice is soft yet engaging. The dark brown eyes are penetrating. She radiates a quiet forcefulness. However, underneath her amiability, steel lurks.

It is this steel and tenacity that propelled a junior prisoner officer employed in the 1980s to become a reform giant in Kenya’s correctional facilities. In a strange coincidence, her second name is allegorical. Kireri implies ‘a big nurturer.’

Former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga acknowledges these nurturing abilities. In the foreword of her memoirs The Disruptor, he says ‘she reigned in the Kenyan Prisons without ruling.’ To others, Wanini is the Florence Nightgale of the Kenya’s prison system; an apt tribute to the restorative work she initiated to mend the prisons’ tattered image.

“I always felt I could do something in my own small way to impact positively on people’s lives,” she says.

For a girl whose childhood dream was to become a flight attendant, fate had other plans. Her true calling was to bring cheer to the most downtrodden amongst us: the inmates.

For decades, Kenya prisons had gained a notoriety for being nasty. They were closed-up system with rigid rules. To put it mildly, they were a hellhole.

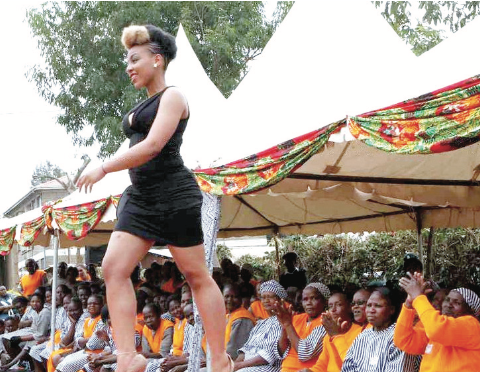

A contestant takes to the stage during past prison beauty contest.

Mutunga says a stint in Kenya prison was tantamount to a death sentence. In Writer’s Prison Diary, Ngugi wa Thion’go writes how inmates at Kamiti Maximum Prison were given tough material to use as toilet papers. The material was so hard he wrote his entire manuscript of Devil on the Cross on it!

Coupled with harrowing tales of torture, starvation, beatings and other forms of brutality, the image of Kenya prisons seemed beyond redemption. Anyone on embarking on a mission to improve the welfare of inmates and wardens was either delusional or crazy.

Wanini was neither; just a dreamer who believed she could trigger positive change in the system.

Almost 40 years after joining the prison department, she has come full circle. The dreamer girl did not conquer the skies aboard KQ birds. Instead, she now soars in the skies of transforming the Kenya prisons system where her name is synonymous with the changes in correctional facilities countrywide.

Her path though has been anything but smooth. Despite anticipating resistance, nothing could have prepared her for what she was up against. Challenging rigid, decades-old systems and practices was never going to be easy. Even with her steely determination, she sometimes became so weary that she almost gave up. However, mountaineering lessons from her youth had taught her to keep going even when the odds were stacked against her.

“Sometimes the resistance was so much that I would feel like quitting but you can’t get to the mountain top if you do,” she says.

Empathy and ability to chart a path through resistance is her most outstanding character. As a young officer, she was touched by the plight of pregnant inmates who struggled to cope with prison life. She saw mothers with young babies subjected to harsh treatment. She observed the inhumane treatment of inmates and felt the frosty relations between junior prison officers and their seniors.

“Ironically, the system was not just brutalising the inmates. The wardens were its victims too. They felt imprisoned,” she says.

Cathartic vent

It was not until she took over as Lang’ata Women Prison boss in the early 2000 that her true reform work started. Tapping into the power of drama, she allowed Bantu and Ndungi Githuku, two renowned thespians, to act out life of inmates and wardens at the facility. It was a brutal performance; a mirror reflection of inmates and wardens’ lives. The drama offered a cathartic vent that gave birth to true reconciliation.

“We saw ourselves anew. It was a very emotional moment and many apologies were exchanged,” she discloses. From then on, the relationship and communication between warden and inmates improved.

Still, the prisons remained deplorable. Basic stuff like soap, toothpaste, tissue papers and beds were lacking. Always a gambler, Wanini’s intuition told her the public would bolster her efforts if it realised the plight of inmates, especially young mothers in prison. She took a risky gamble and allowed the media in. Heart-wrenching images of young mothers struggling to make nappies from old clothes and polythene bags appeared in newspapers. The reaction was overwhelming.

“We got hundreds of donors, institutions, churches and groups who said they wanted to donate stuff to the facility. By opening up, we got many people to help with things inmates could use,” she says.

She was now a reformer on steroids. She introduced beauty pageants, modelling, drama, music, open-days, prayer programmes, computer classes and games at the facility. These efforts were meant to bolster self-esteem of women inmates and restore their pride. Despite such efforts, she still got snarky remarks that she was turning prisons into “holiday homes”.

Later, her transfer to Shimo La Tewa made her the first woman ever to head the 2,000 plus all-male inmates’ maximum security facility. It was here that her mettle was truly tested.

“My first assignment was to enforce general cleanliness. I couldn’t put up with the filth,” she recalls.

Better life

Her programme on institutional and personal hygiene was met with stiff resistance from inmates. They demanded her immediate transfer, saying a woman has no business being a boss in a male prison. Wanini slammed her foot down. Weeks later, the inmates called a truce.

“They realised I wanted them to have a better life,” she says.

After that first test, her reform agenda rolled. She introduced games, family visits and open-door policy. She sought partnerships with organisations and groups to support prison programmes. Families and community flocked to see their loved ones.

Khalid Hussein, executive director of Haki Africa, worked with her at Shimo La Tewa. He calls Wanini as an embodiment of transformation; an Oscar-equivalent praise from this veteran activist.

“She is always seeking ways of reforming the system to get the best results out of it,” says Hussein.

One of the programmes she started was remote parenting, which involved children visiting their mothers in prison for bonding. She says she was devastated after seeing a 15-year-old girl at Langa’ta Women Prison fail to recognise her mother due to long separation. At Shimo, she was touched after a young lifer said he wished Wanini had been his mother.

“I would not be here if my mother was like you,” she recalls him saying.

Her toil has not gone unrewarded. Her trophy cabinet is chockfull of awards, ranging from being Public Servant of the Year Award in 2015 to bagging the coveted 2019 Outstanding Correctional Service Employee Award in Argentina.

Now at the helm of Prison Staff College, optimism is high that her reform agenda will be at the core of training to bring attitudinal change and further bolster reformed prisons’ image.

“This is the hub where professionalism tempered with humaneness is spawned to spread to all prisons in the country. Reform is an ongoing journey,” she says.

While thanking colleagues, friends, family and Kenyans for their support, Wanini insists the society has a key role to play in these reforms. She says the inmates are reformed and equipped with skills like carpentry, masonry and should not be ostracised. She urges communities to accept back and offer former inmates moral support to avoid recidivism.

“When we let them go, the society should accept and support them to get back on with their lives,” she says.