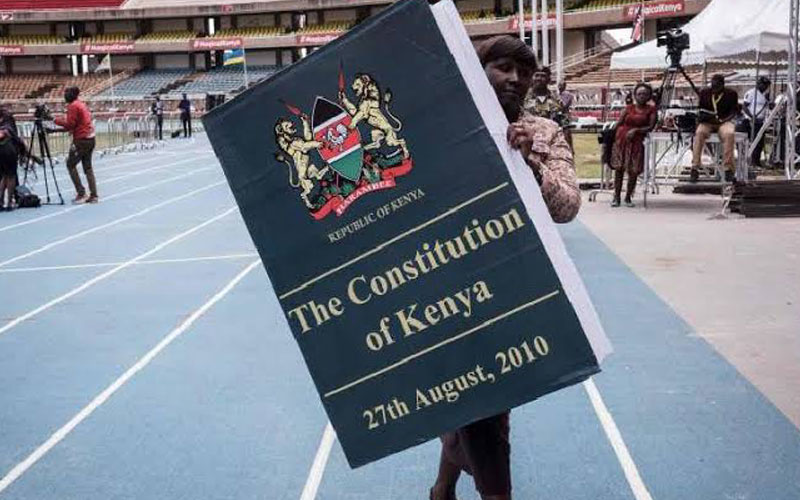

Ten years later, it’s time to reboot statute document

By Mukalo Kwayera, August 24, 2020Mukalo Kwayera @kwayeram

Though regarded one of the most liberal set of laws globally, the last 10 years have been a chokingly painful and demoralising journey of too many misses and few hits for Kenyans whose overwhelming resolve for a more binding and protective Constitution have not been met.

Failure by its legally mandated mangers to implement it to the letter has opened many crevices from which loud and forceful voices have emerged to demand a reboot of the existing document, a decade after its promulgation.

Prior to the unveiling of the current document by President Mwai Kibaki in 2010, the Constitution of Kenya had been a matter of sustained debate that – in the wear and tear of time – took away arm, limb, breath and family in the wake of its agitation that lasted well over 40 years.

History will bear that the crusade for a people-centred, nationalistic and democratic Constitution started way back in 1964, only a year after Kenya attained independence from colonial Britain.

Two important decisions were made that year; first the dissolution of Senate, which had been negotiated for at the famous Lancaster Conference in the lead-up to the country’s Republican status, and the Establishment-driven folding up of opposition party Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu), which had strongly pushed for a devolved system of government dubbed Majimboism, to pave way for the rival Kenya African National Union (Kanu) to remain the de facto (voluntary) political party in the country.

After being hounded out of Kanu in 1966, founding Vice-President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga moved to form the Kenya People’s Union (KPU) through which he and his followers contested the 1969 General Election, winning a handful of parliamentary seats.

However, their celebration was short-lived for KPU was soon proscribed and Jaramogi placed under house arrest until 1978 when founding President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta died.

Assasinations

The assassinations of independence heroes Pio Gama Pinto (1965), Tom Mboya (1969) and Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki (1975) as well as the detention in 1975 of Butere MP Joseph Martin Shikuku, Tinderet MP and Deputy Speaker of the National Assembly Jean Marie Seroney and internationally-acclaimed author Ngugi wa Thiong’o gave fillip to more agitation for an expanded democratic space with freedom of expression, association, choice and worship as the key anchors of the drive.

However, Kenyatta safely navigated through his 15-year regime without so much acrimony on both his diary and statecraft.

It was not until after the 1982 attempted coup, only four years into Daniel arap Moi’s presidency, that repression against dissenting opinion crept into the country’s political system full-throttle, leading to rampant detention of human rights and political activists at a scale never witnessed before in independent Kenya, with university dons, students, lawyers and media practitioners bearing the brunt.

After the coup attempt, the country became a de jure (by law) one party state, thus constitutionally allowing Kenya to be a single party regime.

That was the beginning of the rough and tough autocratic administration that was to characterise Kenya for the next 10 years.

An unpopular voting system known as Mlolongo (queue-voting) adopted in 1988 only worsened the situation as it led to the rigging of popular politicians out of Parliament, only to be replaced by those hand-picked by the Establishment, thus opening floodgates for demands for a change of the Constitution and a multi-party political system.

Defenders of democracy

Political heavyweights and accomplished defenders of democracy such as Shikuku, Masinde Muliro, George Anyona, Koigi wa Wamwere, Charles Rubia, Wasike Ndombi, Mwashengu wa Mwachofi, Kimani wa Nyoike and Chibule wa Tsuma, among others, openly lost in that year’s election in spite of the numbers on their queues indicating they were the victors.

The results of that election marked a crescendo in the push for a new Constitution. The losers in the poll teamed with others, like then Kiharu MP and Transport Minister Kenneth Matiba who had lost in the Kanu grassroots elections, to go all-out in the demand for a new constitutional dispensation, a spirited push that led to some of them such as Matiba, Charles Rubia, Raila Odinga, lawyers John Khaminwa and Gitobu Imanyara being detained without trial.

Civil society, religious leaders, the so-called alternative media, lawyers under the umbrella of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) and other professional groupings teamed up to stage a relentless push for a new constitutional order, a commitment that led to the removal of Section 2 (A), a clause that legalised single-partyism, from the Constitution to pave way for plural politics.

However, in spite of the country having adopted a new political system, the roots of monolithic governance remained heavily embedded in the new order.

Indeed, whereas a considerable number of agitators had been elected to Parliament in the 1992 election, they were mostly in the Opposition and, therefore, with very little influence in the manner of driving government policies, a development that called for an extended drive for more freedoms and liberties.

The period 1992-2008 was mainly defined by what has come to be described as the struggle for the second liberation, an era that saw the country transforming from an authoritarian State to a more accommodative one, especially after Moi’s exit from power in 2002.

Election of then Opposition leader Mwai Kibaki to the Presidency after Moi’s peacful departure from State House paved the way for a new dawn insofar as re-looking into the Constitution was concerned.

Kibaki put in place mechanisms that re-energised the agitation for a new set of laws through the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission chaired by eminent law scholar, Prof Yash Pal Ghai whose efforts through what has come to be known as Bomas draft culminated into the holding of the 2005 referendum in which the government side lost to the Opposition fronted by Raila.

Post-election violence

However, Kibaki was not done yet. Following the post-election violence that gripped the country after the disputed results of the presidential contest in 2007, a team of international mediators led by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, brought in at the recommendation of the African Union, proposed a raft of administrative, political and legal changes to be made in a bid to take back the country on the right footing.

It was from those recommendations that a Commission of Inquiry chaired by retired South African judge, Justice Johann Krieggler, was appointed to probe the causes of the violence.

Kriggler’s team came up with far-reaching propositions, among them adoption of a new Constitution.

It was from those recommendations that Kibaki, once again, set in motion a path that led to the referendum that gave the seal of approval to the current Constitution which was proclaimed by Kibaki on August 27, 2010.