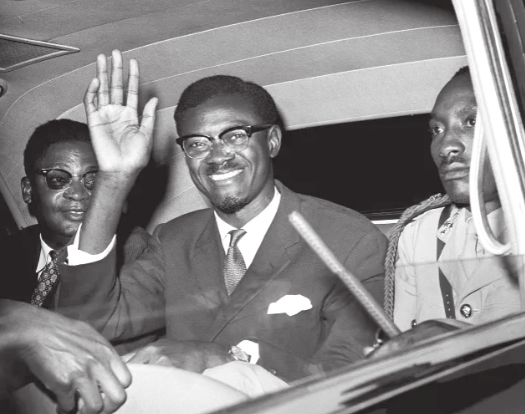

‘Symbol of resistance’: Lumumba, the Congolese hero killed before his prime

By Al Jazeera, January 18, 2025Shortly before noon on a Thursday in June 1960, 34-year-old Patrice Lumumba stepped up to the podium at the Palace of the Nation in Leopoldville (current-day Kinshasa) with a dream to unite his newly liberated country.

Standing before dignitaries and politicians, including King Baudouin of Belgium from which the then-Republic of the Congo had just won its independence, the first-ever prime minister gave a rousing, somewhat unexpected speech that ruffled feathers among the Europeans.

“No Congolese worthy of the name will ever be able to forget that it was by fighting that [our independence] has been won,” Lumumba said.

“Slavery was imposed on us by force,” he continued, while the king looked on in shock. “We remember the blows that we had to submit to morning, noon and night because we were ‘negroes’.”

With independence, the country’s future was finally in the hands of his own people, he proclaimed. “We shall show the world what the Black man can do when working in liberty, and we shall make the Congo the pride of Africa.”

But this was a promise left unfulfilled, as just six months later the young leader was dead.

For years murkiness surrounded the details of his killing, but it is now known that armed Congolese men murdered Lumumba on January 17, 1961, aided by the Belgians and with the tacit approval of the United States.

Sixty-four years on, Lumumba remains a symbol of African resistance, while many Congolese still carry the burden of his aborted legacy – whether they favoured his ideas or not.

‘His death distressed me’

“When I learned of Lumumba’s death, I was shocked,” said 85-year-old Kasereka Lukombola, who lives in the Virunga quarter of Goma, in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

His gold-coloured Western-style house, unusual in this region, was built during colonial times and is a reminder of the vestiges of nearly 80 years of Belgian rule.

Lukombola was born during World War II, he said. “At that time, a Black man in Africa could not oppose the white settlers for certain reasons, including the colour of his skin and the fact that he was enslaved. Those who dared to challenge the whites were either imprisoned, beaten up or killed.”

He was 20 when Lumumba was killed. Though it took weeks for news of his death to emerge, Lukombola remembers that night as being one of the “darkest” he has ever known.

“I remember being in my village in Bingi [when I heard the news]. I regretted it, his death had distressed me. On that date, I didn’t eat, I had insomnia,” he said, adding that he still remembers it as if it were yesterday.

Lukombola accuses the Wazungu (a term meaning “foreigners”, but generally used for Belgian colonists) of having been behind the assassination.

“The Belgians were racially segregating the Congo, and Lumumba outcried against this. He encouraged us to fight tooth and nail to get rid of the colonisers,” he said.

“He had discovered certain plots by the colonists against us, the Congolese people. They wanted to enslave us forever. That’s when the Belgians developed a hatred against him, which led to his assassination.”

Lukombola believes that if Lumumba hadn’t been killed, he would have transformed the country into a veritable “El Dorado” for millions of Congolese, based on the vision he had for his people and the continent as a whole.

Tumsifu Akram, a Congolese researcher based in Goma, believes Lumumba was killed on the orders of certain Western powers who wanted to keep hold of Congo’s natural wealth.

“The decision to eliminate the first Congolese prime minister was taken by American and other officials at the highest level,” he told Al Jazeera.

Though Lumumba had friends both inside and outside the country, “as numerous as they were, his friends were not so determined to save him as his enemies were determined and organised to finish him off,” Akram said. “His friends supported him more in words than in deeds.”

Only a tooth remained

Just days after Lumumba delivered his June 30, 1960 Independence Day speech, the country began to fall into chaos. There was an armed mutiny, and then the secession of the mineral-rich province of Katanga in July. Belgium sent troops to Katanga. Congo then asked the United Nations for help, and although they sent peacekeepers, they did not deploy them to Katanga. So Lumumba reached out to the Soviet Union for assistance – a move that alarmed Belgium and the US.

In September, President Joseph Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba from government, something he ignored. Soon after, a military coup led by Congolese Colonel Joseph Mobutu (later known as dictator Mobutu Sese Seko) fully removed him from power. Lumumba was placed under house arrest, from which he escaped, only to be captured by Mobutu’s forces in December.

On January 17, 1961, Lumumba and two associates, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, were then taken to Katanga by plane – soldiers beat and tortured them on the flight and at their destination.

Later that day, all three were executed by a Katangan firing squad, under Belgian supervision. Their bodies were at first thrown into shallow graves, but later dug up, hacked into pieces, and the remains dissolved in acid.

In the end, only one tooth of Lumumba’s remained, which was stolen by a Belgian policeman and only returned to Lumumba’s relatives in 2022.

In the years since the killing, Belgium has acknowledged that it was “morally responsible for circumstances leading to the death”. Meanwhile, information has also come to light exposing the US CIA’s involvement in a plot to kill Lumumba.

A ‘big mistake’?

At his home in Goma, Lukombola recounted all the “firsts” he’s lived through during his country’s complicated history, including taking part in the first municipal election of 1957 – in which he voted for Lumumba’s Congolese National Movement (MNC) party “because I was convinced it had a great vision for our country. It was out of a sense of pride,” he said.

He recounted being around during the riots of January 4, 1959; the proclamation of the Congo’s independence on June 30, 1960; the secession of Katanga and South Kasai between July and August 1960; and the joys of Zaire’s economic and political pinnacle in the mid-1960s.

Having lived through the reign of all five Congolese presidents, Lukombola understands the “enigma” that is the DRC and has seen how much it can change.

His only regret, he said, is that many historic events occurred after Lumumba had passed on. “If he were alive, he would restore us to glory and greatness.”

However, not everyone looks at Lumumba’s legacy with such awe and kindness.

Grace Bahati, a 45-year-old father of five, believes Lumumba is at the root of some of the misfortunes that have befallen the DRC and that the country continues to grapple with.

According to him, the first prime minister was too quick in wanting immediate independence for the Congo, while the country lacked sufficient intelligentsia to be able to lead it after the departure of the Belgians.

“Lumumba was in a hurry to ask for independence. I found that many of our leaders were not prepared to lead this country, and that’s unfortunate,” Bahati told Al Jazeera. “In my opinion, it was a big mistake on Lumumba’s part.”