Nothing kills folklore like loss of vital biodiversity

By John Obiero, September 24, 2020With all this modernity around, nothing could be as threatened as biological diversity of plant and animal life on earth.

We only seem to understand development and progress in terms of infrastructure, industry, our own security and health without a thought for destruction, degradation, replacement and disturbance we have caused on the ecosystem. But why should we care about maintaining variety of life forms on earth?

Biodiversity is beneficial to humans because our survival is dependent it. This is why its security is an all-time global debate.

But I will digress into a local example to downscale the debate to something we can relate to and reflect upon.

I come from a village perched on a plateau inhabited by barely 7 sub clans, 200 households and no more than 1,200 people.

Our people derived their livelihood from basket making, livestock keeping, hunting and gathering until late 1970s.

From the 80s, however, a few young men ventured into Kisumu, 25 km away in search of market for their products.

It did not take long before traders noticed the beautiful craft , which became so popular that they accompanied young men back into the village for better bargains.

Today, our village is settled by mixed groups of people whose arrival dates back to the traders.

With passing of time, livelihood, economic activities and lifestyle changed a great deal.

In only 40 years, there is no more bushmeat, no indigenous vegetables, no wild fruits, no hunting and no more basket making. We have been modernised, so to speak.

Of all these, loss of the basket making craft has been the most devastating t. Craft products would be sold for money or exchanged for other goods; given out as trophies or gifts; used ornamentally; or, in processing agricultural products for storage, winnowing, and as haulage containers. Unfortunately, the craft and enterprise has become unsustainable.

Bushes where pliable plants grew natively have been cleared for human settlement and crops.

The few basket makers left now travel tens or hundreds of kilometres to forests or marshes in search of them. With raw material facing extinction within the village, the craft, industry and biodiversity are threatened.

Disappearance of pliable plants also means intergenerational transmission of technique in the community is disrupted.

Such loss is compounded by other challenges occasioned by harsh socio-economic realities such as high rates of youth unemployment, inflation, decline in animal and crop yield, rural poverty, ignorance and disease.

Still, there is another loss that would be difficult to turn around: communal lifestyle and folklore that defines it.

Our people came together in village enclosures to make baskets, telling stories, exchanging knowledge about beliefs, passing on customs, and mentoring younger people.

Experienced basket makers would share their knowledge of plant varieties, animals, ethnic medicine and conservation practices with apprentices.

Without pliable plants used for the craft, the craft dies, and with it both community spirit and indigenous knowledge system..

But all is not lost, the little village and other villages like it can still defeat poverty, regain its livelihood, and bring back folklore.

Reviving the craft enterprise goes together with systematic regeneration of the raw material.

Its cultivation is an important step in biodiversity conservation which will in turn rekindle intergenerational transmission of the craft in the community.

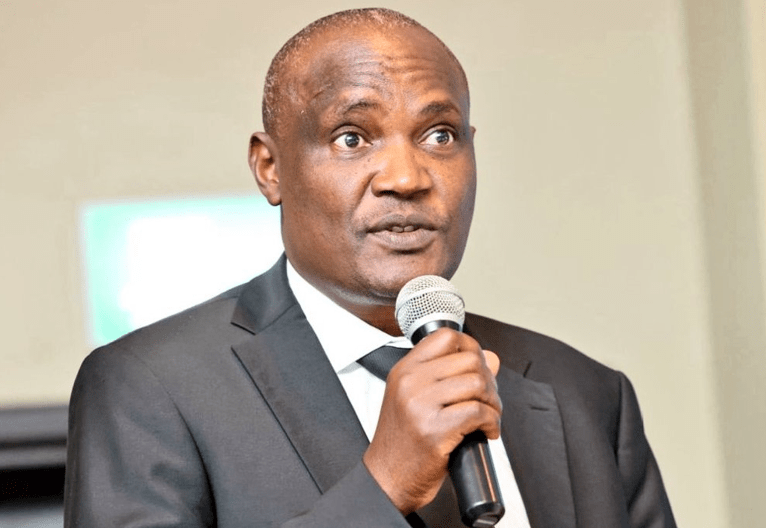

— The writer is a senior lecturer, department of Linguistics and Literature, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Scienece and Technology

More Articles