Experts predict deadly DRC floods to recur every 2 years

By Alberto Leny, April 23, 2025The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is being featured on the global news for all the wrong reasons, ranging from conflict, exploitation of its mineral resources and the impacts of climate change.

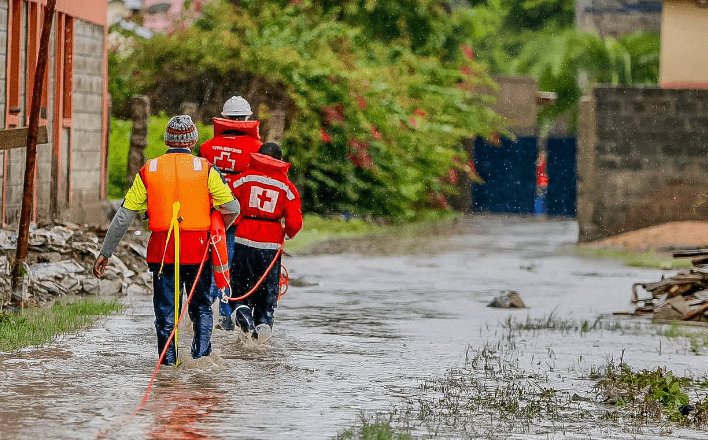

Following recent heavy rainfall and flooding that left 33 people dead, thousands displaced and homes as well as property damaged in the capital Kinshasa, weather experts are warning Congolese authorities to prepare for the occurrence of such disasters more frequently.

The floods in Kinshasa came after a worsening humanitarian situation in eastern DRC where government forces and Southern Africa Development Cooperation (SADC) troops have been overrun by Rwanda-backed M23 rebels in a long-running war. The rebels have captured the cities of Goma and Bukavu, and large swathes of eastern Congo. The violence has resulted in thousands of deaths and the displacement of millions since January.

Torrential downpours in Kinshasa, which started on April 4, caused an overflow of the N’djili River, a tributary of the mighty Congo River, as the subsequent deadly floods inundated half the city’s 26 districts, cut off major roads, submerged key infrastructure, and severed access to drinking water.

Now, experts are warning that extreme weather events and accompanying disasters could occur every two years at current levels of global warming.

Heavier rains

Scientists working with the World Weather Attribution (WWA), which assesses how climate change affects extreme weather, say such periods of heavy rainfall are no longer rare in today’s climate with global warming of around 1.3°C.

Data from two weather stations in Kinshasa indicates that seven-day spells of rainfall have become about 9-19 per cent more intense since 1960, and rains could become heavier with fossil fuel warming, the WWA researchers warned.

The scientists observed that while there was not enough data to determine the influence of climate change on the latest flooding episode, it aligns with scientific studies on rainfall in the DRC and projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for Central Africa.

Kinshasa’s location next to the Congo River and its dense population, most of whom live in informal housing, make the city prone to deadly floods and landslides, according to the WWA researchers.

The researchers noted that with the city’s population of nearly 18 million expected to double in 20 years, continued deforestation for construction, building of houses in flood-prone riverside areas as well as limited drainage and sewage systems, flooding is expected even with moderate rains.

Shaban Mawanda, policy and resilience adviser at the Red Cross-Red Crescent Climate Centre, told the authoritative UK-based Climate Home News digital publication that the severe effects of the floods “are not surprising” because Kinshasa is ill-prepared for periods of extreme rainfall, which have become common occurrences.

The WWA researchers highlighted how high levels of poverty and the worsening conflict in eastern DRC have made the Congolese people more vulnerable to extreme weather.

Conversely, climate change is making it even harder for fragile states, such as DRC to get ahead as frequent spells of heavy rain are destroying homes, wiping out crops and cancelling economic gains, said Friederike Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College.

She told Climate Home energy transition reporter Vivian Chime in the publication’s latest edition that with “every fraction of a degree of fossil fuel warming”, the weather will get more violent and create a more unequal world.

The 18 researchers who examined the DRC flooding– drawn from universities and meteorological agencies in the DRC, the Netherlands, Rwanda, Sweden, the UK and the US – emphasised that they could not quantify the influence of climate change on the recent heavy rains, partly because of limited investment in weather monitoring and climate science in Africa, revealing the lack of weather data limits preparedness.

According to Chime, Dieudonne Nsadisa Faka, a climate expert from the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS), said the evidence from the two Kinshasa weather stations showing an increase of up to 19 per cent in rainfall intensity “is not the smoking gun our study was looking for”.

Frustrating situation

The failure highlights a deeper problem, explaining how climate science has long overlooked much of Africa, particularly the Central African rainforest region.

The WWA researchers explained that globally, research has focused mainly on extreme weather in wealthy countries, meaning the changing risks of events in many African countries are not well understood. Out of seven WAA studies that produced inconclusive results, four examined weather events in Africa, the researchers said.

They highlighted that more investment in weather stations and climate science in Africa is needed to help countries understand shifting extremes, prepare for the future and prevent deaths such as those experienced in the Kinshasa floods.

Africa needs more weather attribution studies and better datasets to understand how its countries are impacted by climate change, as well as financial support to tackle the threat, said Joyce Kimutai, one of the study’s authors and a researcher at Imperial College London’s Centre for Environmental Policy. As an African scientist, Kimutai said she finds today’s situation “incredibly frustrating”.

“Climate change is not a problem caused by Africa. Our continent has contributed just 3-4 per cent of global emissions, but it is getting pummelled by extreme weather and still isn’t receiving funding for adaptation promised by wealthy countries at global climate summits,” she said in a statement to the media.

Media reports said the deluge in Kinshasa saw nearly half of the DRC capital’s 26 districts severely affected, with floodwaters submerging key infrastructure, including the main road to the N’djili International Airport.

The hardest-hit areas are the poorer outskirts of the city. In at least 16 communes, access to drinking water has been cut off due to submerged water facilities. The downpour that continued for days from 4 April followed unusually heavy rains at the end of March, leading to high rivers even before the rainfall that led to the flooding.

The researchers in the study collaborated to assess whether human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the seven-day rainfall that ultimately led to the flooding in Kinshasa.

Spatially, the analysis focused on the river basin where the N’djili River and the Congo River combine, which includes cities other than Kinshasa, but while the heavy rain affected large parts of the region, the impacts were concentrated in Kinshasa.

The main findings were that Kinshasa is prone to frequent and deadly flooding during the rainy season (October to May). It is built next to the Congo River, and several rivers run directly through the city, including the N’djili.

With close to 18 million people, Kinshasa is one of the most densely populated cities in the world. Around 70 per cent of the urban population lives in dense informal housing, much of it prone to floods and landslides. In 2022, more than 100 people died following a similarly heavy downpour.

From a hazard point of view, the study notes that the event, as observed in 2025, is not rare. Similar periods of heavy rainfall are expected to occur on average every second year in today’s climate, which has been warmed by 1.3°C, due to the burning of fossil fuels.