Develop consistent dress code for President

Clothes define a man or a woman as a statement of policy, philosophy and worldview. In Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni is easily identified with his long-sleeved, untucked white or yellow shirts with a big hut on his head. The yellow colour is a symbol of his political party.

Julius Nyerere in Tanzania was defined by his simple African suits associated with Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda. President Kaunda would often be seen splendidly attired in his khaki outfit with proper inside neckwear and a white handkerchief in hand.

Years later, when Nelson Mandela would be president of South Africa, he travelled to Indonesia and got converted to a near Batik wear that he popularised in his regular appearances.

Dressing is part of a person’s statements informing their nonverbal communication. The appearance of the CEO symbolises an organisation’s stability, statement of purpose and how one seeks to function.

The dress could indicate the intention of the person wearing it, whether they are approachable or not, and often could define their mood, or they could use it to define the mood of their surroundings.

Nations such as China have taken this a notch higher. Dressing would be used to communicate an individual’s station in an organisation. A simple organisational etiquette is to be conscious of the boss’ dress and to learn never to outdo the boss.

If the boss prefers an open shirt throughout the week, then the staff do well to follow suit and do the same. When the boss is not consistent, the rank and file will be confused, affecting their productivity. In August 2014, then US President Barack Obama appeared in a tan suit at a White House presser on then ongoing military conflagration in Syria. The question was whether the US administration should upscale its military presence in the middle eastern country.

Experts on dressing soon could not have enough of it. How could the most powerful man in the world show up in a tan-coloured suit? Was it that he was sending a subtle message his administration was yet to decide what to do? Previously, Obama’s dressing had been limited to black, charcoal or navy-blue suits. In the psychology of colours, black/navy blue suggests power and authority. They point to who is in charge. Not only do they communicate sophistication, but also indicate timeless elegance. These darker colours tend to hide the bulging parts of the body.

On the other hand, earth tones tend to build rapport and create a sense of willingness to engage. Blue communicates loyalty and dependability, while charcoal is sometimes viewed as communicating trust levels.

The colour of the suit is one thing, but it must be balanced with the shirt and tie. The length of the tie is important and should touch the belt, not too much below it. It is important to wear a matching belt and shoes. Serious officers cannot afford to have the tie hang somewhere on their tummy.

Outfits enable us to know how seriously an individual is taking his office. This is why government officials should have officers in charge of their wardrobes. That responsibility is, in fact, a duty to the country they represent.

It is not so much for a public officer to decide how to dress, but rather for the office to decide for him how he is dressing.

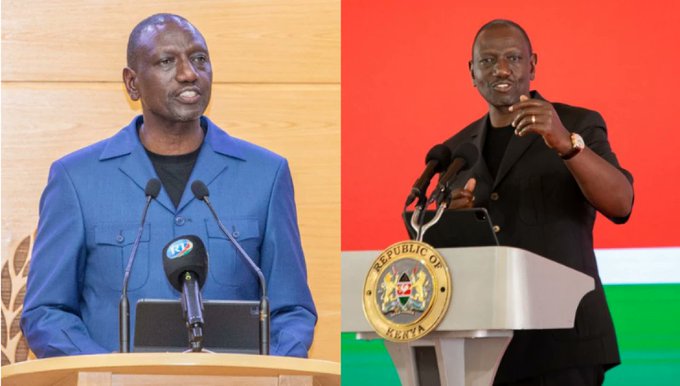

A President’s oscillation and experimentation with a range of outfits sends a confusing message regarding his self-identity.

In the history of the president’s office, Moi and Kibaki so far have been standard bearers. They considered the office’s psychology and its associated power. This far into President William Ruto’s term, the wardrobe officers should be done with their experiments and develop a consistent identity for the President.

— The writer is Dean, School of Communication, Daystar University