COP29 carbon markets deal faces credibility test

Negotiators from 190 countries entered the final week of the COP29 talks in Baku, Azerbaijan with a gritty determination to resolve sticky issues in the eight main subjects of discussion at the world climate conference.

These include:- Climate finance, Loss and Damage, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and emissions reduction, The Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), Unequal climate impacts and Locally Led Adaptation (LLA), Nature-based solutions (NbS) and Indigenous rights, Carbon markets and Geopolitical context, conflicts and tensions

The seventh topic – carbon markets – made significant progress at the end of the first week of the Baku talks when new global trading ruling rules were adopted, expanding inclusion but drawing anger from some quarters.

What is carbon trading? Also known as carbon emissions trading, carbon trading is the use of a marketplace to buy and sell credits that allow companies or other parties to emit a certain amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, mainly carbon dioxide.

The carbon trade came in response to the Kyoto Protocol adopted in Kyoto, Japan, in December 1997 that called for 38 industrialised economies to reduce their GHG emissions between 2008 and 2012 to levels 5.2 percent lower than those of 1990.

Carbon accounting

Carbon trade has led to using carbon accounting to measure the impact made by companies, individuals and governments.

The value of the carbon is based on the ability of the country to store it or prevent it from being released into the atmosphere.

A new set of global credit trade market standards were agreed on at the end of the first week of COP29 following years of deadlock. Under the guidelines, a bigger number of entities could join a more regulated voluntary carbon credit trading system to reduce emissions.

Known as Article 6.4, delegates agreed on the rules for establishing a system that allows trade in carbon credit between individual companies, under the supervision of a centralized UN body.

These include how to validate, verify and issue credits.

Another option (Article 6.2), allows countries to set their own terms to trade carbon credits bilaterally. Countries were not able to agree on the standards for either option before COP29.

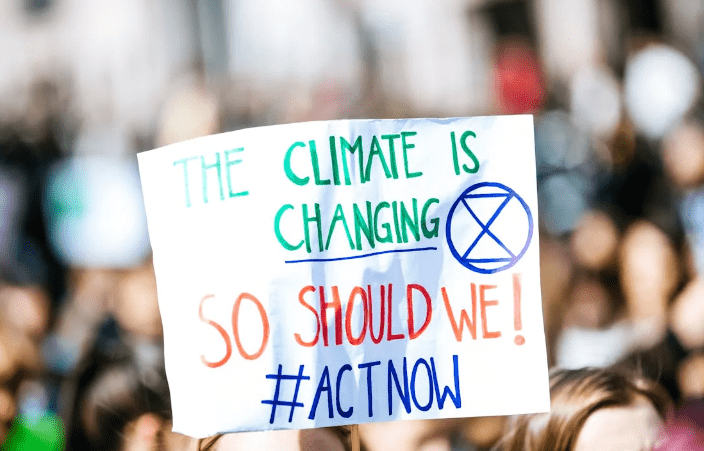

Under the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels by the end of the century, countries have committed to green goals, including slashing carbon emissions.

The new deal negotiated and agreed on in Baku could “reduce the cost of implementing national climate plans by $250 billion per years by enabling cooperation across borders,” the COP29 presidency announced, hailing the outcome as a “game-changing tool to direct resources to the developing world.”

However, it was not adopted without controversy.

More recognition

According Chung-Hua Institute of Economic researcher Je-liang Liou, the agreement is more recognition from countries of the new rules, but negotiations are still ongoing and details are being worked out so they are not fixed.

“In the previous COP, the supervisory body usually drafted a bill for countries to discuss and decide if they approve it or not. But this year, the body of Article 6.4 approved their own draft before COP29 started so it became more of a situation for countries to give their votes,” Liou explained to Voice of America (VoA).

The hasty process drew ire from some countries, including Tuvalu’s. It said that “adopting decisions without prior consultations by the governing bodies does not reflect the Paris agreement’s party-driven process,” said the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Some climate advocates also said the agreement isn’t a success, as regulations have been an issue for voluntary carbon trading in the past.

“We should be very concerned in the Global South, especially if we don’t have sufficient safeguards in place to protect against the possibility of land grabs, human rights abuses and forest-based livelihoods, gender and indigenous interests,” said South African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute climate policy coordinator Tra Nair van Ryneveld.

She cautioned against carbon trading as part of “false solutions” that distract from work to be done on phasing out fossil fuels.

Amid the prospect of companies joining in carbon trading, voluntary carbon offsetting projects from companies were revealed to be ineffective in serving their purpose, according to a 2023 investigation from The Guardian newspaper and trade watchdog Corporate Accountability.

Avoid emissions

Nearly four in five of the top carbon offset (the practice of using avoided emissions or enhanced removals to compensate for GHG emissions) projects are considered “worthless” as they can’t guarantee cutting greenhouse gases, the report found. In carbon markets, for example, a buyer can secure and retire a carbon credit in lieu of directly reducing their own emissions.

Despite the criticisms, Article 6.4 can be a “push toward stronger regulation and accountability” and better transparency in climate finance, according to Luca Taschini, director of the Centre for Business, Climate Change and Sustainability at the University of Edinburgh.

For non-UN member regions like Taiwan that have long been excluded from discussions and the country-to-country trading system, the expanded system under Article 6.4 can be positive news, says Lou, as it allows companies to invest in projects, potentially allowing its participation.

The extended carbon credit system – if set up and starts next year – can boost governments’ climate ambitions, amid nations’ looming submission deadline for a new climate plan by February 2025.

Self-ruled Taiwan imports almost all of its energy from other countries. Under its climate goal to source 15 percent of its power from renewables by 2025 and reaching net-zero in 2050, slashing emissions in the medium term can be challenging and carbon markets can be beneficial for the island.

Taschini said Article 6 allows countries to invest in actions beyond their borders and raise global ambition. “This is because, even if all NDCs are met, we will still fall short of our climate goals.”

While many countries ask for more ambition, the window of opportunity to get this done is narrowing. Large disagreements on how carbon market registries should be handled exist. The negotiations in the final week of COP29 are going to be difficult.

The involvement of ministers and high-level negotiators in the final leg of COP29 should not result in significant quality compromises for the sake of a deal, says Isa Mulder, an expert on global carbon markets at Carbon Market Watch.

With difficult and crucial climate finance negotiations occurring in parallel at COP29, she says it is essential to ensure a strict firewall between the new climate finance package and Article 6 (and the voluntary carbon market).

“It is key for NGOs and many countries that Article 6 and the and the voluntary carbon market are not inappropriately mixed into the climate finance deal. UN Trade and Development Secretary-General Rebecca Grynspan recently said that carbon markets are not a panacea…they are not a substitute for official development assistance or for climate finance flows.”