AU needs early warning conflict resolution mechanism

It looks like conflicts in Africa are not about to disappear any time soon. The frequency with which they keep popping up shows countries are yet to evolve strong conflict resolution mechanisms.

Across the African continent, trouble is brewing, mainly driven by political elites consumed by personal selfish agendas, at the expense of the best interests of the long suffering citizens of those countries.

The highest potential for conflict occurs in the run up to, during, and after presidential elections.

The African Union (AU) remains the continent’s biggest hope for forestalling conflict before it becomes a full-blown crisis, as is happening in too many countries.

Working in concert with the regional bodies like ECOWAS, EAC, and SADC, it has the capacity to intervene before matters get out of hand.

In Mali, the AU flopped badly. Mali’s President, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, was overthrown by the military after months of unrest that were triggered after the long delayed parliamentary elections were held in April.

The AU was nowhere as people of Mali protested the botched elections.

Only after the president was deposed did AU intervene, condemning the coup. Of course, nobody in Mali, where crowds danced in the streets celebrating Keita’s downfall, took them seriously.

In Gambia, however, they did very well. Regional leaders, under the umbrella of ECOWAS and with the backing of the AU, demanded that President Yahya Jammeh leave office after he was beaten by Adama Barrow in the December 2016 presidential race. Jammeh had refused to hand over power.

ECOWAS organised Barrow’s swearing in a neighbouring country, and the region’s leaders mobilised a regional military force ready to enforce the transfer of power.

The AU can have the best programmes in the world for Africa’s development, but these will come to zero if the continent is aflame.

Only when the AU is able to successfully intervene in conflicts in African countries will it become a force for empowerment of Africans.

All other efforts pale into insignificance when compared to its inability to assist resolve conflicts in the continent.

Currently, one of the most ominous signs of trouble looming is the third term push by incumbents facing term limits.

Without fail, this issue has triggered mass protests and deaths. The latest is Ivory Coast, where President Alassane Outtara has declared he is going for a third term against the country’s constitution.

This has triggered deadly unrest where dozens have already been killed, and the country is now on a precipice. Everybody knows how this will end. Badly. The AU is deathly quiet.

In The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), then incumbent Joseph Kabila, clearly unwilling to leave power as mandated by constitutional term limits, delayed the election for two years in 2016, citing administrative and financial challenges.

This triggered mass protests and violence for two years as citizens protested. Many died, and more were injured, until Kabila reluctantly agreed to step down.

Zimbabwe is in the throes of a major political crisis, with the regime there undertaking a brutal repression of citizens unhappy with a worsening economy, and a bungled response to the Covid-19 pandemic in the country. The AU remains rooted to the spot, unable to marshall a response.

The AU needs to intervene at the first signs of trouble in a country. It needs to develop an early warning instrument that enables it to trigger a response mechanism.

Such a response mechanism can comprise a group of eminent African statesmen, especially the growing band of retired presidents, and nonpartisan local stakeholders in a country, to start engaging and monitoring before the situation gets out of hand. Once open conflict starts, the situation rapidly spirals out of control.

To back up its intervention with the necessary robustness and potency, AU needs to work hand in hand with the International Criminal Court (ICC), to keep rogue politicians in check.

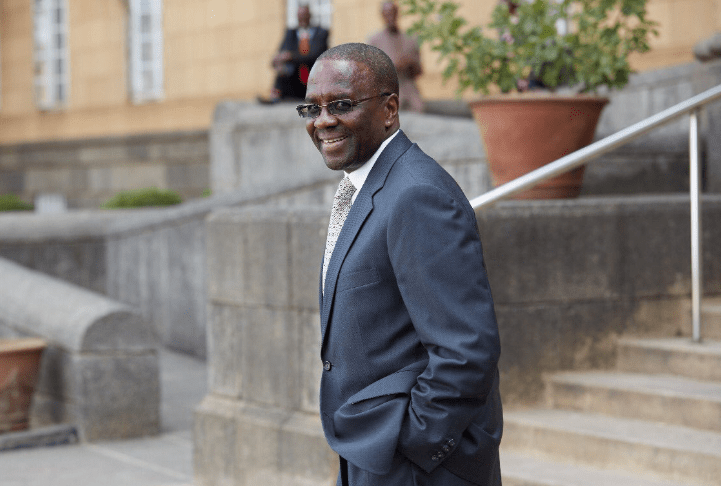

If the current Chairperson of the AU Commission, Moussa Faki, wants to be more than just a figurehead who warmed the top seat at the headquarters in Addis Ababa, this is the one thing he can do for the people of Africa, for which he will be remembered for a long time to come. – [email protected]