To whom does constitutional moment belong?

Many countries have drafted their constitutions on the backdrop of crucial political events that have inspired the values and mechanics contained therein.

These past events that signify constitutional moments have taken varied forms in history including revolutions (as it was with France in 1789 and Libya in 2011) and the attainment of independence, as is the case with post-colonial societies.

There are also those that argue that constitutional moments are not always irregular or necessarily created through painful historic events.

For this school of thought, even a routine and peaceful change of executive power provides the impetus for constitutional change where the succeeding regimes define for themselves, what the constitution means and whether they will endorse or change its existing demands.

At their core, however, all constitutional moments are characterised by a change in the status quo, an ushering of new beginnings and even the rebirth of nations.

Constitutional moments also matter because they signify the ideals and ambitions of a generation.

They propagate fresh ideologies and shared visions for future generations, which ultimately give a country its character.

Ideally, they belong to the people to whom constitutional changes seek to serve.

Over time a distinctive five-step cycle has emerged for constitutional moments.

First there is always signaling that a constitutional change is likely to occur. Institutional actors through speech or actions make it known it is a possibility.

This is followed by a period of proposing , with elaborate process of constitutional reform- often done in ways that engulf public attention and consume energy of political actors.

What follows is a process of triggering, where proposals are bolstered by an intervening event such an election, an uprising or overt shows of dissatisfaction with the status quo by the public.

This could last for a period of time eventually giving way to ratification. At this stage, one or more institutions resistant to change give in and pave way for constitutional change.

As a last step the legislature (or even judiciary) consolidates the new changes into the existing regime, making them part of the new constitutional order.

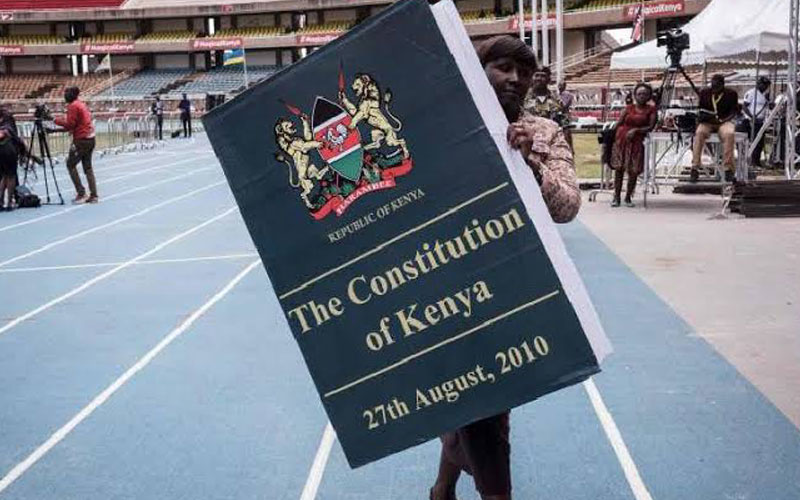

As our Kenyan experience shows, we have and continue to experience most of the above events and processes.

Our past constitutional moments have included our fight for independence and the clamor for multi-partism.

During these periods a myriad of institutional actors such as parliamentarians, religious leaders and civil society activists signaled, proposed and championed for constitutional reforms.

Divisive elections and gross abuse of civil and political rights acted as triggers for reforms and in the end, changes were willingly or unwillingly, ratified and consolidated in our existing constitution.

Fast-forward to today, it is believed initiatives such as Punguza Mizigo, Ugatuzi and Building Bridges Initiative are signaling a constitutional moment. Representation and resource allocation are driving factors .

Parliament recently passed the Referendum Bill 2019, which provides a road map for future referendum processes.

The bill provides for, amongst other things, a 14-days period within which county assemblies must forward decisions on a popular initiative bill to parliament for approval.

While the bill focuses on constitutional changes through popular initiative, members of the national assembly have intimated that such draft bills will still pass through the normal parliamentary processes before becoming law.

This provides for participation at all levels of governance. It also broadens discussions on constitutional amendments beyond the Elections Act and Articles 255, 256 and 257 of the Constitution.

Naturally, there are spirited debates on what a constitutional moment should look like for Kenya, when it should occur and which actors should be advocating for it.

What is clear however is that we are thinking out loud about who we are and where we want to go as far as our constitutional democracy is concerned. — The writer is an Advocate of the High Court and comments on topical issues