State must cut its coat according to its cloth

Kenya is going through the budget circle, and one word is missing in all the discussion: balancing the budget. The focus of the discussion has been primarily on increasing taxes, increasing the efficiency of collecting taxes and borrowing.

Listening to the Treasury mandarins, it appears they are beaming with pride. They successfully floated Eurobond and infrastructure bond, both oversubscribed. The Kenyan credit facility, the President announced, was attractive to lenders.

However, the borrowing is primarily to pay a previous debt. In layman’s terms, we borrowed last time to pay for whatever, then the debt fell due; we did not have money to pay back the lenders, so now we borrowed again to pay the debt we owed.

There is a catch: the second borrowing to cover up for the first is at a higher interest rate, above ten per cent. The second debt is certainly more expensive than the first one. But there is quite some satisfaction in the corridors of our money managers that this has been done successfully. The evidence is that the exchange rate for the dollar is coming down.

In a recent discussion, the Principal Secretary for the Treasury was waxing lyrical, blaming Kenyans for complaining about paying taxes. He said that compared with other economies, the tax rate in Kenya was still low.

That may be true. But just imagine the range of taxes levied in Kenya: rental income, value-added tax, capital gains tax, withholding tax, excise duty, income tax, tax on interest, turnover tax, corporate tax, payroll tax, customs duty, stamp duty, and you could go on. This is before you come to tax on fuel and the now infamous housing tax.

The rate at which these taxes are charged in Kenya may differ from those in other countries. However, how these taxes are used in other countries differs from how we use taxes in Kenya.

Taxes are supposed to be applied towards supplying services to the people who pay taxes. Such services include conveniences, cleaning the neighbourhood, providing security, etc. But in our case, most infrastructure development is done through borrowing.

Then, there are no services that would make one proud of paying taxes. Most of the hospitals are going without medicine. We have the police, but they hardly provide services; our best image of police is of uniformed men and women waiting all day along country roads collecting money indiscriminately from businesses.

Instead, citizens have to organise for their private security. Education is supposedly free, yet there is still a raft of charges that must be paid. Citizens must organize their waste disposal and infrastructure layout in their communities. If you have a call of nature in the urban, you must pay to pee.

It may be that the Treasury mandarin was speaking of the formal taxes, but then there are the informal taxes, which are charged on the go by the informal sector.

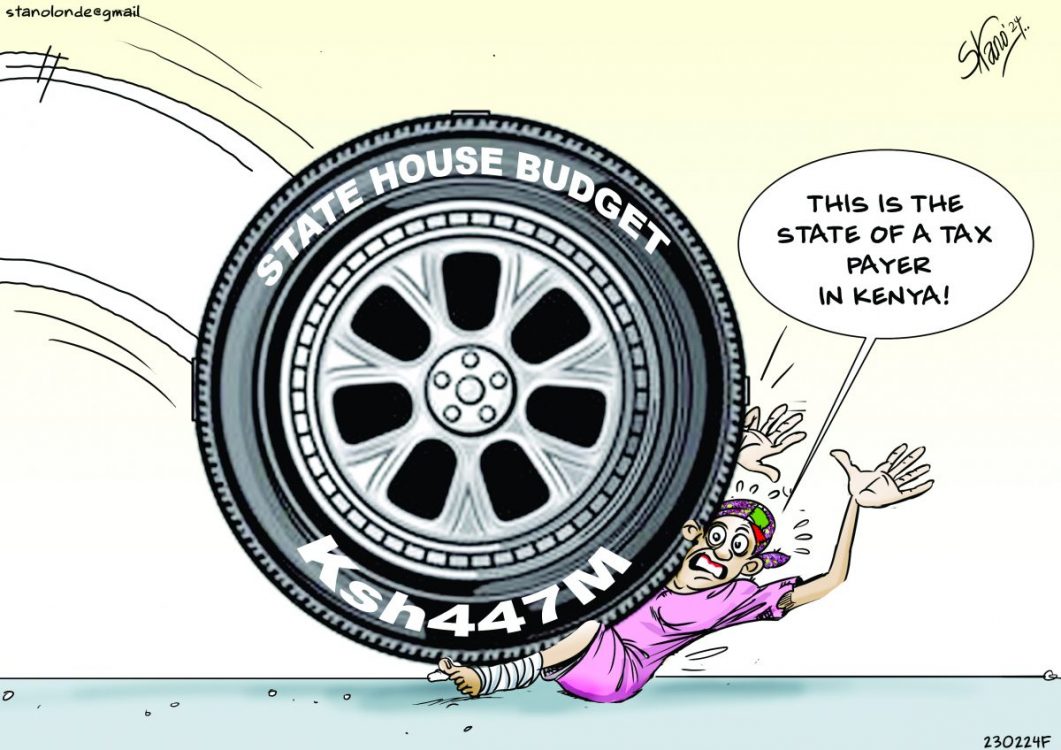

Why doesn’t the government cut its clothe according to its size? The average citizen may not lose much; after all, where does the tax collection go? Primarily into meeting recurrent expenditure. What consumes this recurrent expenditure is often wastefulness: bloated bureaucracy, wastefulness in foreign trips and unmitigated allowances, unnecessary costs in government among others.

The government can cut these down and the nation-state will still be provided for. Can the government account for every penny it collects? The report by the auditor general is telling. It is always a catalogue of cost centres that cannot be justified or explained.

The balanced budget vocabulary needs to start featuring in our conversations prominently. Why this is not a campaign platform for those seeking elective offices speaks more about our appetite for consumption than prudent management of national resources. But it is towards the prudent management of national resources that we need to focus.

—The writer is dean, School of Communication, Daystar University