State has failed us in taming false prophets

Even in a world where new media is the buzz, very little will replace traditional media’s watchdog role in society.

Africa has been glued to the BBC documentary on the late Prophet TB Joshua and the happenings at his Synagogue Church of All Nations this past week.

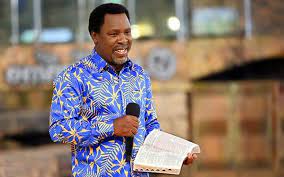

While he lived, the Nigerian preacher was a sensation everywhere. Dark-skinned, smooth, well-cropped hair and a goatee to go with it, TB Joshua appeared to shun the more extravagant attires of his contemporaries.

Instead, he came across as simple in his shirts and save for the dramatic speech styles; there was nothing out of the ordinary in his preaching. But it is in that simplicity that his lethality lay.

He attracted people from near and far, both simple and sophisticated. Presidents and prime ministers trooped to his Synagogue in search of powers and answers; whether they got them or not is a different story that only they can tell.

The then Zambian President, Frederick Chiluba, an avowed evangelical in his own right, pleaded with his countrymen to watch TB Joshua’s television shows, and one can only imagine how many picked their remote controls and switched over to Emmanuel TV.

But inside the church, if the BBC documentary is authenticated, the Synagogue appears to be anything but a normal church. The details of the BBC’s two-year investigation are out there for all to see. There are many questions that the documentary should raise in our minds. For a start, what is the role of religion in society, and how should citizens relate with their spiritual leaders?

The happenings in the Synagogue Church of All Nations are not isolated. Across the globe, and probably more so in Africa, many similar movements may be only less successful relative to TB Joshua. In Kenya, we have our Shakahola story, the depth of the depravity, which we still do not know.

The claims of many a preacher have been staggering. They can heal this or that sickness, make this or that miracle happen, provide this or that power, and all you need is to believe, buy this or that ointment, and carry this or that handkerchief or piece of cloth with you. It seems simple.

Allow the preacher to touch this or that part of your body, follow this or that instruction given by the man or the woman of God and believe this or that pronouncement. Desperate people have followed through.

Africa particularly provides fodder for these movements. For a start, our administrations have failed us, and many services are unavailable, leaving people at the mercy of those able to make spectacular claims.

Hospitals are not working, and where they do, they face many limitations. The needs of the people can not be easily met, there is a lack of money to take children to school, and there is lack of mechanised means of agriculture, thus relying on rain-fed farming, leaving individuals susceptible to spectacular expectations from people who claim connection to the spiritual world.

Some interventions by governments to provide services could reduce dependence on the spiritual superstars. The soul of man is, however, restless, and seeking spiritual connection is real. But this is where governments could come in and guide through regulatory frameworks that could smoke some of these groups out before they do too much damage.

At least the media’s traditional role can step in once in a while. The task of documenting such a story is expensive, time-consuming and not given to the short attention span characteristics of this generation. Neither is it something the taunted alternative media of the present age can deliver.

Social media is given to the quick and spectacular; the scroll-down type and number eight will shock you, all dispensed in minutes. Stories often still take time to tell, and more so, the good and impactful stories. It is for reasons such as this that the necessary steps to prop up good journalism must be made, and governments may have a role to play in it.

— The writer is Dean, School of Communication, Daystar University