Ruto team’s communication efforts still muddled

Never before in the history of independent Kenya has a presidential administration developed such mystical faith in the perceived power of words. Grand declarations are made and iterated as if they are an end in themselves.

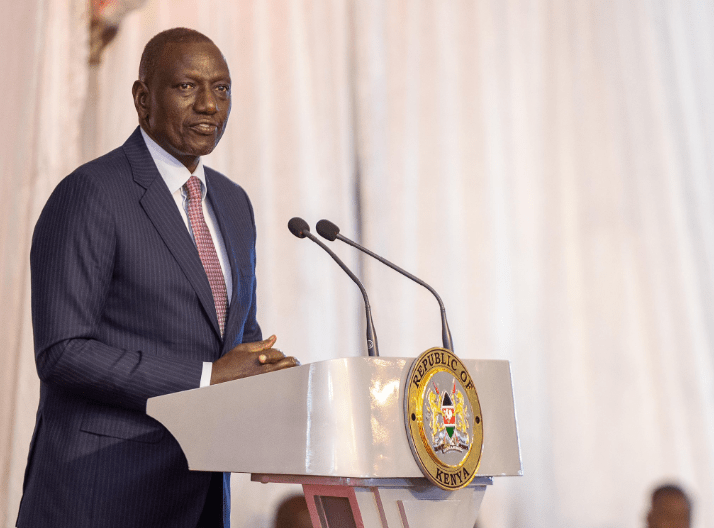

The belief seems to be that the more President Ruto and his operatives say things, the more believable they will become, regardless of what the truth might be. The President’s current great enemies are his social media critics, whose narratives about his administration he and his backers naively think they can shatter or drown out.

But the messaging counter-offensives are lame, ineffective and ultimately futile, many written in tedious self-conscious academic jargon or bureaucratese. Take, for example, a short message purportedly from a top government official that was shared recently on social media forums.

The official wrote about Kenya’s five-year (2022-2027) development plan, saying (in my translation of it into simple English) the government has five main goals for 2025 – keep the economy stable, help people find jobs and make money, help families earn more, improve how we make and sell our products, and finish building important roads, bridges, and other projects.

Sounds good, even soothing, in translation, doesn’t it? But the original text obscured the message by using the formal bureaucratic language favoured by people in politics and administration, liberally sprinkled with abstract concepts like “division”, “bigotry” and “chauvinism”.

It was also noun-heavy (Kenyans are educated to think in nouns), with complex phrases and economic and political jargon that could only be understood by a small group of people (“prevailing macroeconomic stability”, “strategic infrastructure projects”, “value chains”), and moral-political posturing (“spectacular relegation of family values”).

Reading the message, I was jolted by the use of the old-fashioned, biblical allusion “three score years” (meaning 60 years), a phrase apparently thrown in there not to make things clearer but merely as a rhetorical flourish.

Now, if the point of the message was to communicate useful and potentially consequential information to an audience, why didn’t the official use simple language that most people could understand?

We can only speculate. The official has an academic background and maybe the Kenyan education system has taught him that complex language is a marker of authority.

Academic and bureaucratic language can also cover government inaction or problems with development projects (and many Ruto projects are beset with many problems). So this kind of language helps bureaucrats by making it harder for the public to understand what is or isn’t actually being done by the government. It’s safer for a bureaucrat to say, “Implementation challenges have necessitated a strategic reassessment of timeline deliverables,” instead of, “We’re behind schedule.”

This complex language and specialised vocabulary is the most notable feature of government communication, with journalists quoting blocks of text from official documents (as they have been trained to do) and ending up passing on incomprehensible mumbo jumbo to an uncomprehending audience of mostly ordinary citizens.

In recent months, the Ruto administration had belaboured the point that it had a “messaging problem” – that it was achieving monumental things but those successes weren’t being communicated effectively to the general public. But it seems poor communication is still a problem in the administration.

Supposedly important information is often obscured by the very words used to convey it, failing the basic purpose of communication, which is to inform and engage with the public.

Clear, straightforward language would better serve public understanding. George Orwell captured this well in his essay “Politics and the English Language”, noting: “Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

Some citizens have observed that what Ruto needs is not pillorying for his response to critics but empathy. Until about a decade ago, Kenyan Presidents never had to deal with social media and the onslaught of misinformation and disinformation often shared on digital platforms. The President is an unfortunate victim of his times but his response is self-defeating.

— The writer is a Sub-Editor with People Daily