My life-changing encounter with ‘Girl from Tetu’

My time of torment would come a month later. Now working for the then fiery Society Weekly political magazine, after two attempts to petrol-bomb the premises, our offices at Tumaini House were one morning eventually raided by police.

Six of us were arrested on the eve of Good Friday, kept incommunicado throughout the weekend and transported to Mombasa to be charged on Tuesday with 11 counts of sedition.

I was walking to the office at the parking lot between KenCom and Tumaini House when it all started.

It was the eve of my 26th birthday, on Thursday, April 1992, when I was arrested.

I was the News Editor and Pius Nyamora was the Publisher and Editor-in-Chief, Blamuel Njururi the Managing Editor, and Mwenda Njoka the Deputy Managing Editor. Mwangi Chege was the Deputy News Editor while Laban Gitau and Macharia Mugo were senior reporters. Fred Geke, George Obanyi and Mburu Mucoki completed the sub-editors’ desk.

From the open parking area, I was followed by a mass of bodies of about 60 plain-clothes police officers through the stairs to the third floor of Tumaini House. At the reception, the editorial secretary Janet Marende had barely greeted me by calling my name while asking, “Kwani wewe hujashikwa?” when the the police pounced on me.

After being held at the Ongata Rongai police post were transported to Mombasa on Monday, ahead of being charged the following day with 11 counts of sedition together with Nyamora, his wife Loise, Njoka and Gitau.

We spent four days with hardcore criminals at Shimo La Tewa Prison after being denied bail by Mombasa Chief Magistrate Karanja Kanyi.

As we were being charged in Mombasa, dozens of my family members who had travelled from Kabras in Kakamega to Nairobi were hopping from one court to another expecting us to appear there, as they had no clue of our whereabouts.

My days at Shimo La Tewa were the most excruciating. Apart from the nauseating meals and horrifying stories from my fellow inmates – most of them capital offenders – we were forced to squat naked every morning on two lines (based on gender) for medical check-ups.

The purported medical examination entailed a warder pinching our private parts – the testicles – and if one writhed in pain, they were declared fit. I still don’t know how women were tested. It was a demeaning experience for all of us.

All these troubles were created by a cover story in our magazine titled “Kilonzo Go Home”, which was an assault on then Police Commissioner Philip Kilonzo (father of former Yatta MP Charles Kilonzo) whose brutal stewardship of the law enforcement agency had assumed unimaginable proportions.

Chief Magistrate Joseph Karanja Kanyi finally granted us bail. It was during the days of the original Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD). One of the so-called Ford Six founder members, Ahmed Bahmariz, mobilised Mombasa politicians and business people to stand guarantee for our bail. I was about to miss a guarantor when journalist Njuguna Mutonya (then the Mombasa bureau chief of Nation Newspapers, and now deceased) came forward in the nick of time and presented his car logbook to secure my release.

We had the first decent meal at Splendid Hotel that evening and, together with members of the Release Political Prisoners (RPP) lobby group led by Njeri Kabeberi, took the train back to Nairobi.

In the capital city, Kabeberi’s RPP team took us directly to the All Saints’ Cathedral sanctum, where we were received by Prof Wangari Maathai, Provost Peter Njenga and the mothers of political prisoners for joint prayers and shared our experiences for hours.

That Easter encounter only strengthened my relationship with Wangari, whom I would later accompany to various parts of the country, touring grabbed forest land as she raised her voice against violations of human rights and other injustices.

Tea plantation

One day, while on a tour of Kieni forest in Kiambu County, we were almost shot by Administration Police officers whom we found guarding a large tea plantation inside the forest.

When Wangari asked who owned the tea plantation, she was told, “Hii ni mali ya mkubwa. Tokeni hapa saa hii ama tuwaweke risasi saa hii”.

We drove off in haste as the APs shot in the air several times. With old hand John Makanga Ngorongo on the steering wheel, we navigated the road and found our way to Lari, then Limutu and onto the Nakuru-Nairobi highway and back to Wangari’s residence in South C.

Lawyer and multiparty crusader Gitobu Imathiu Imanyara some years back tried in a media outlet to open the lid on the long-kept secret regarding the failure to unite the nascent Opposition to present a single presidential election in the 1992 elections.

It so happened that after the Kanu regime bowed to pressure and allowed plural politics in Kenya, the reformist lobby group FORD morphed into a political party.

However, ego trips, sheer bigotry and ethnic supremacy fights took centre stage, leading to its split into two.

One faction, known as Ford-Kenya, was led by Jaramogi and the so-called Young Turks, while the other was led by Kenneth Matiba, Martin Shikuku, George Nthenge and Ahmed Bahmatiz.

Sensing a Kanu victory in the 1992 General Election, Wangari attempted to unite the feuding FORD parties.

A legman of sorts, I and Makanga were always around to witness the Wangari-led unity talks under the banner of a new lobby group known as the Middle Ground Ground (MGG).

After a series of night meetings for several weeks, the MGG parleys flopped.

None of the warring wings was willing to step back on their irreducible minimums.

Wangari’s viewpoint was that since Jaramogi was the oldest of the reform advocates and had fought for the reintroduction of multipartyism longer than anyone else, he should be allowed to run for President with Matiba as his running mate.

That idea floundered terribly as ethnic undertones came to the fire.

While Wangari was accused by the political elites from her Kikuyu tribe of pushing a Luo agenda, the Ford Kenya hard-tackling negotiators, on the other hand, posited that she was quietly anticipating the elderly Jaramogi’s imminent death and therefore preparing the ground for the return of the Kikuyu to power.

No agreement was reached. Both parties went their own way, arguing that they had more supporters in the country than any other. They were beaten at the polls by Moi’s Kanu.

Though he himself was never a participant in the MGG talks, the arguments around Jaramogi’s age and possible demise were attributed to Raila.

Insiders stated that on a daily basis, after the night negotiations at Wangari’s residence, the Ford Kenya team would reconvene at a different place after briefing Jaramogi of the proceedings to analyse the situation.

Raila was said to be the key player at the private intra-Ford Kenya power talks and the conclusions that came out of them.

Wangari was a very strong-willed personality. Tough, principled and undending. She valued her integrity a lot. She would never waver on her decisions, which she arrived at after long and deep reflection.

She preferred to write her own press statements and speeches. She would only ask you to proofread the statement, but not alter the content in any way or form.

One day, I noticed that all the 18 paragraphs of her press statement – a no-holds-barred open letter to then President Daniel arap Moi – started with the words “Your Excellency Sir”.

I asked why she had done so. She replied: “I just want to prove to the world that I’m a good girl. Yes, a good girl from Tetu.”

That is when I started calling her The Green Girl from Tetu.

On another occasion, she invited me, Makanga, Kimau Kilonzi and two lawyers to help her draft a speech she was to deliver in Manila, Philippines, on the linkages between the environment and human rights.

We worked on the speech from 8 pm to 5 am, going through it over and over again together with her.

Nobel intrigues

In the end, she rejected it. She was not satisfied with the content. She wanted something harder and more piercing than what we had put on paper. She opted to give her speech directly without any notes or paper work.

I have never known why Kenya’s celebrated writer Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o has never won the Nobel Prize for Literature in spite of being nominated several times.

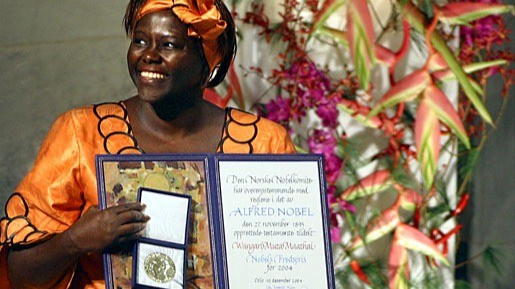

A meeting I attended after Wangari won the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize seemed to provide me with some insights.

Three weeks after Wangari returned from receiving her Nobel Prize in Oslo, Makanga and I were among the few privileged guests invited for a private dinner at the Nairobi Safari Club at Lilian Towers in honour of the Nobel laureate.

The guest of honour was the then Norwegian ambassador to Eritrea who had done duty in Nairobi before being deployed to the Horn of Africa nation.

It was revealed there that it was that ambassador who had proposed Wangari for the Nobel Peace Prize while he still served in Nairobi.

It was also there that it was revealed to me by a Norwegian lady seated to my right that one needs to have been nominated by a Norwegian national or institution to win a Nobel Prize.

That is when I started thinking about Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s fate. I still do. .

-The writer is a Revise Editor with People Daily; kwayeram@yahoo.co.uk