Kenya’s quest for electoral integrity

Kenya’s electoral history is a dynamic narrative of struggle, reform, and resilience. From the early post-independence days, when electoral bodies served as mere appendages of the executive, to the hard-fought gains of multiparty democracy and constitutional reforms, the country’s electoral management has undergone significant transformations.

Yet, the specter of political interference continues to cast a long shadow over the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). The appointment process for electoral leaders, once the exclusive prerogative of the sitting president, has evolved toward a more structured and transparent system.

However, the persistence of political meddling, the appointment of inexperienced commissioners, and the failure to fully embrace international best practices continue to undermine Kenya’s electoral integrity. As the nation embarks on yet another selection process for the IEBC chairperson and commissioners, a pressing question emerges: Will this moment mark a turning point, or will history repeat itself?

Electoral leadership in Kenya has historically been a battleground for political control. Past commissions were frequently stacked with appointees loyal to the executive, ensuring that elections served the interests of the ruling party. Figures such as the late Duncan Ndegwa and Jackson Angaine presided over electoral bodies during an era when elections were largely ceremonial, reinforcing single-party dominance.

The return to multiparty democracy in 1992 was expected to usher in a new era of fairness, but subsequent electoral chiefs like Zacchaeus Chesoni and Samuel Kivuitu found themselves embroiled in highly contested elections, culminating in the deadly 2007 post-election crisis. What does this tell us about the price of compromised electoral leadership? These historical episodes underscore a fundamental reality: the independence and credibility of an electoral body hinge on the integrity of the appointment process.

Beyond the chairperson, the composition of electoral commissioners has been pivotal in determining the credibility of elections. Before the 2010 constitutional reforms, the executive wielded near-total control over the appointment of commissioners, selecting individuals based on political allegiance. This approach eroded public trust and fueled allegations of electoral malpractice. How can the public place faith in an electoral process when its referees are handpicked by political players? The lack of clear legal provisions governing the selection process further entrenched a system where electoral outcomes were frequently disputed, posing a severe threat to Kenya’s democratic stability.

A significant milestone in Kenya’s electoral reform journey came with the 1997 Inter-Parties Parliamentary Group (IPPG) arrangement, an effort to depoliticize the appointment of electoral commissioners. This informal agreement between the ruling Kenya African National Union (KANU) and opposition parties allowed for a more balanced Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) by granting opposition parties a say in the selection of commissioners.

The IPPG model introduced a measure of credibility, but its lack of constitutional anchoring meant that future administrations could disregard it. This vulnerability was exposed in 2007 when President Mwai Kibaki unilaterally appointed new ECK commissioners, triggering widespread election-related violence. If history has taught us anything, is it not that informal agreements, no matter how well-intentioned, are no substitute for legally binding frameworks?

Political neutrality

Notably, the success of the 2002 general elections was largely attributed to the IPPG reforms. That election saw Kenya transition from decades of KANU rule to the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) government led by Kibaki. The relatively peaceful and credible nature of the polls was, in part, a result of a more balanced ECK composition, highlighting the importance of inclusive and consultative approaches to electoral reform. Shouldn’t this serve as a reminder that transparency and fairness in electoral appointments are key to national stability?

The pre-2010 system of appointing ECK commissioners was fundamentally flawed. With appointments driven by political considerations rather than competence, electoral bodies became instruments of incumbency rather than impartial arbiters of the democratic process. The lack of structured public participation, rigorous vetting, and institutional checks on appointments rendered the system deeply vulnerable to manipulation. Electoral commissioners, who should have been neutral referees, instead became enablers of political interests, eroding public confidence in the electoral process. Can a democracy truly thrive when its elections are managed by individuals whose allegiance lies with political elites rather than the electorate?

Recognising these systemic failures, the 2010 Constitution introduced a more structured and independent selection process. The creation of a Selection Panel to oversee the shortlisting, interviewing, and recommendation of candidates for IEBC leadership was a major step forward.

Parliamentary approval was incorporated into the process to limit executive overreach and enhance public trust.

However, political influence remains a persistent challenge, as parties continue to push their preferred candidates into the Selection Panel, undermining its neutrality. If the panel itself is politicised, can the commissioners it appoints truly be independent? As Kenya embarks on another round of appointments for the IEBC chairperson and commissioners, the country has an opportunity to draw from global best practices. Established democracies such as Canada, Germany, Australia, and India offer valuable lessons on structuring an independent electoral body.

In Canada, the Chief Electoral Officer is selected through a merit-based process overseen by an independent parliamentary committee, ensuring that only individuals with proven expertise in election management assume office. Similarly, Germany’s Federal Returning Officer is a non-partisan civil servant with extensive experience in election administration, chosen for competence rather than political alignment. Why does Kenya continue to struggle with political interference when other democracies have managed to insulate their electoral bodies?

One of Kenya’s most glaring missteps has been its tendency to appoint electoral leaders with little or no prior experience in managing elections. Unlike mature democracies where election commissions are often led by seasoned administrators who have risen through the ranks, Kenya frequently taps individuals from legal, financial, or academic backgrounds.

These appointees must navigate a steep learning curve in an already high-stakes political environment, weakening institutional memory and efficiency. Alarmingly, in the current selection process for the IEBC chairperson and commissioners, none of the 11 shortlisted candidates has prior experience in managing elections. This raises critical concerns about their capacity to handle Kenya’s complex electoral system, mitigate political tensions, and ensure credible outcomes. Shouldn’t electoral commissions be led by individuals with hands-on experience in election administration rather than those learning on the job?

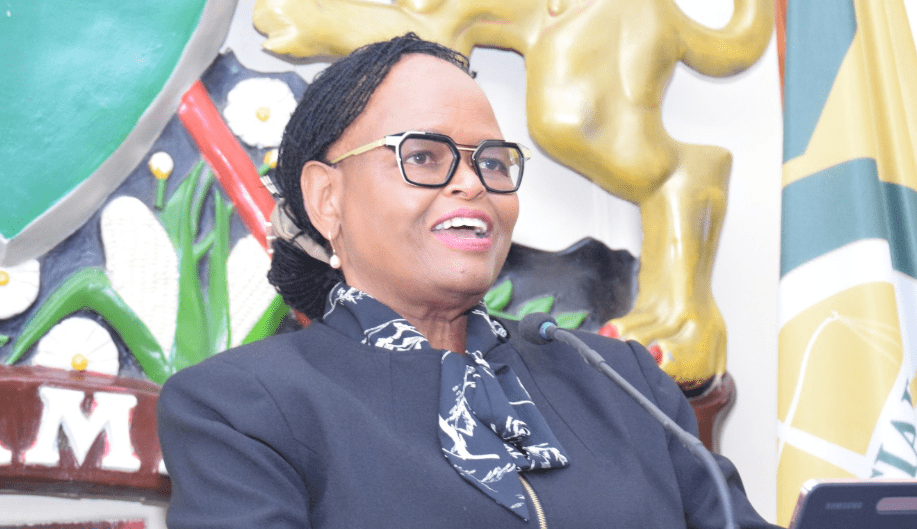

Further complicating matters is the question of political neutrality. Among the shortlisted candidates, Charles Nyachae, a former chairman of the Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution (CIC), is regarded as a close associate of President William Ruto.

Similarly, Joy Brenda Mdivo, who chairs the Kenya Power Board, played an active role in President Ruto’s 2022 campaign and served on the United Democratic Alliance (UDA) dispute resolution committee. Duncan Ojwang, another candidate, was part of the Kenya Kwanza technical team during bipartisan talks with the Azimio coalition. These affiliations raise fundamental questions about the impartiality of the selection process: Can individuals with strong political affiliations truly uphold electoral independence? For the IEBC to function as a truly independent and credible institution, the chairperson and commissioners must demonstrate strong leadership and crisis management skills.

Kenya’s electoral landscape is frequently turbulent, and only individuals capable of making decisive, independent judgments while upholding the rule of law can withstand the pressure. Moreover, technological competence is increasingly crucial in election administration.

With the growing role of digital voting systems, biometric voter registration, and electronic result transmission, Kenya’s electoral leaders must possess a strong grasp of election technology to ensure secure and transparent processes. Can an electoral body succeed in the digital age if its leaders lack the requisite technological expertise?

While the 2010 Constitution has laid a robust legal framework for the IEBC’s leadership selection, the ultimate success of the process depends on a collective commitment to integrity, transparency, and meritocracy. By embracing best practices from established democracies and prioritising experienced election administrators, Kenya can solidify the independence of its electoral commission. A transparent and merit-driven selection process is not just a procedural necessity—it is a cornerstone for the consolidation of democracy and the prevention of future electoral disputes. Will Kenya rise to this challenge, or will it allow history to repeat itself once more?

The writer is a History Lecturer & UASU Chapter Trustee, Alupe University-Kenya email: