IEBC electoral reform delay is justice denied

By Alberto.Leny, December 10, 2024Justice delayed is justice denied is a metaphorical phrase and an early 19th-century proverb. It is also a legal maxim that means if a remedy is not provided to an aggrieved party in a timely manner, it is the same as having no remedy at all.

The phrase has been a central part of domestic and international policy agendas because of its economic and human rights consequences. It has also inspired reforms to improve the performance of national judiciaries.

However, legal experts say there are potential drawbacks to resolving cases more quickly, such as possible decline in the overall quality of the justice system.

Confining ourselves to the Kenyan context, citizens have been adversely exposed to the extremities of delayed, hence denied justice, mostly in three Es – economic justice, environmental justice and electoral justice.

While delayed economic justice holds a vice-like grip on the majority that unleashed the deadly mass protests and rejection of the Finance Bill, 2024, delayed environmental justice is equally exerting pressure on the human rights scale amid the devastating impacts of climate change.

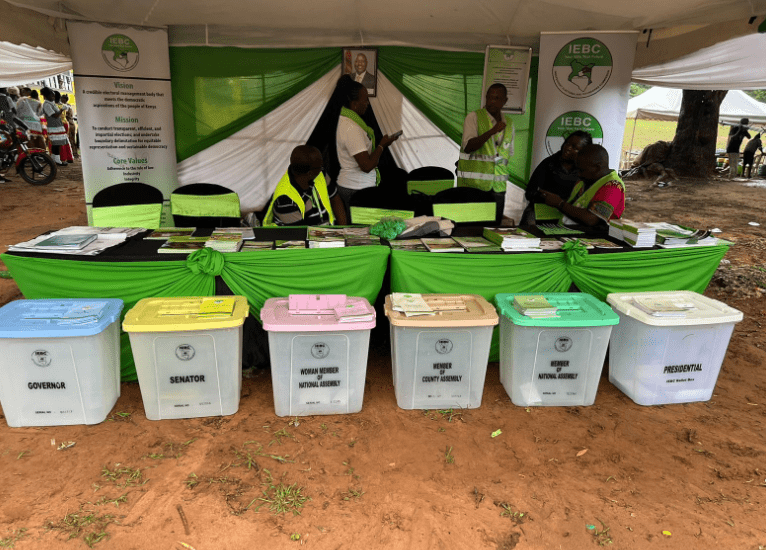

Yet delayed electoral justice remains the biggest threat to national political stability as a result of the failure to reconstitute the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) after the tumultuous 2022 presidential election, with just three years before the next one in 2027.

A worrying scenario not helped by arrogant politicians bred on a culture of impunity, ethnic-based falsehoods couched in deceptive nationalistic jargon, ethical depravity and corruption.

In 2001-2002, the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission comprehensively captured the expectations of Kenyans on the issues they wanted addressed in a new constitution after decades of injustices under wanting national leadership.

It was anticipated that the new constitution would promote the people’s participation in governance through democratic, free and fair elections. That was not to be, as the 2007-2008 post-election violence threatened to plunge the nation into an abyss.

Kenya fell into the trap of entrenched ethnic divisions fuelled by social and economic exclusion, corruption and the winner-takes-it-all politics prevailing today.

A national accord was agreed to form commissions to review the elections, violence, and truth and reconciliation. The outcome was the Kriegler Report on the elections, the Waki Report on the post-election violence and the Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission.

The accord recognised then, as now, that there was a national crisis that required a political solution. Just as some features of the Constitution at the time made violence more likely, the delay in reconstituting the IEBC is a looming danger that poses serious electoral and credibility questions, compounding the real motives of the current political incumbency.

So, the accord urged a new constitutional review process that recognised the need for a long-term framework to address the causes of the post-election national crisis and identified six areas that the nation, its citizens and leadership must holistically address.

They were constitutional, institutional and legal reform, land reform, poverty, inequality and regional imbalances, unemployment among the youth, national consolidation and unity, transparency, accountability and impunity.

Sadly, the birth of the 2010 Constitution created euphoric but short-lived hopes of a free and democratic system of government that enshrines good governance, constitutionalism, the rule of law, human rights and gender equity.

Today, 14 years later, Kenya is more or less in a similar stillbirth situation, with the same political cast charting an elusive roadmap for democracy, electoral justice and national redemption.

— The writer comments on national affairs; albertoleny@gmail.com

More Articles