Helping children born with clefts smile again

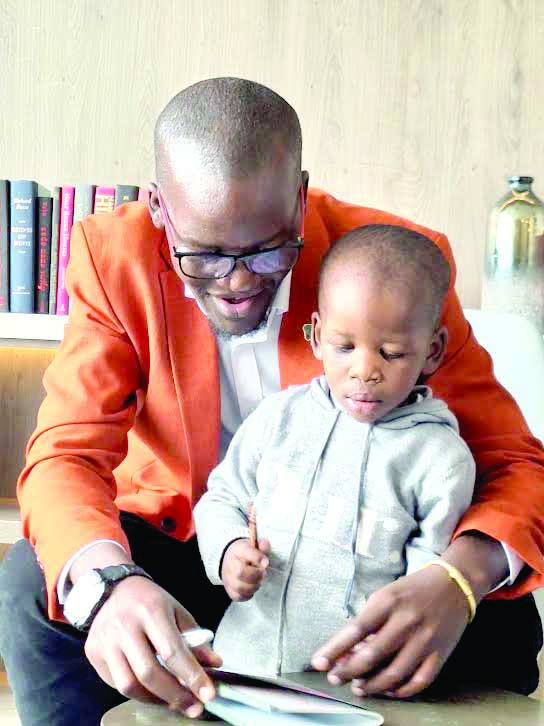

By Lilian and Kwach Wakhisi, September 11, 2023Bruce Orangi is a family man, married and a proud father to two lovely boys— Othniel and Uriel. He was born with clefts, and his two sons were also born with a cleft lip and palate.

At the age of five, when he became conscious to everything that was happening around him, he noticed that people were treating him differently. He had a scar on his lip and a hole on the upper roof of his mouth.

“It was not easy considering that not so many people knew a thing about cleft lip and palate. The biggest challenge was the stigma he faced since I was always considered abnormal,” says Bruce who currently works as a data specialist with an IT background.

Difficulty eating

“Generally, growing up, I had challenges with speech. People could not clearly understand me whenever I spoke. In addition to that, there were meals I could not eat well as they would come out through my nose,” he recounts.

Bruce counts himself lucky since he was able to undergo corrective surgery at the age of 10 after some missionary doctors visted Kenyatta National Hospital to perform surgeries for cleft lip and palate patients.

He offers: “I have had to get other corrective surgeries after that, especially on my palate as recent as this year. You know when people you meet treat you as if you are not normal, that feeling tends to interfere with your mental health. But since the repairs, I have lived a normal life.”

As a parent with children also born with cleft lips and palates, Bruce says it was easier for him to accept the situation because he had been through it before, however, parents who are new to it struggle a lot.

“My wife was shocked when she first found out that our children, especially our first born had been born with a cleft lip and palate. But I helped her accept and embrace the challenges that came with it. Feeding times were most difficult. The child is not able to latch on its mother’s breast hence you have to find other means to feed it, such as introducing formula,” he says.

His sons aged five and two years old have both had corrective surgeries. The first born has had three while the second boy has had two surgeries.

“The boys are leading a normal life. In fact, the eldest boy is attending school and his speech has improved tremendously over time. The second born is even better with speech and loves singing,” says Bruce.

“Parents need to understand that cleft lip and palate is just like any other deformity. It is correctable and we have organisation’s across the country who are here to help. The society needs to understand that cleft lip and palate is not a curse, hence we should not hide our children. We should treat them like any other child. Remaining positive is important and in such cases, there is need for partners to support each other,” he says.

Another parent, Winnie Paul says her12-year-old daughter was born with cleft lip and palate, and she is glad she overcame all that and is now a singer.

Corrective surgeries

“I discovered that my girl had a cleft lip and palate after birth. It came as a huge shock,” says Winnie, a teacher by profession. “In her early months, whenever friends, neighbours or relatives visited, they would make some awful comments about my daughter’s appearance. I would be asked to explain why she has a mark and whether she had fallen down and hurt herself. It was disheartening,” recalls Winnie.

Her daughter began her corrective journey when she was three months old and along the way, other corrective surgeries have been performed.

“I sought for treatment at Metropolitan Hospital in Nairobi’s Buruburu estate courtesy of Smile Train, which has an amazing team. They have turned out to be okay and I am greatful that this organisation has walked with us through this tough journey. My mother has also been my greatest support system and we are glad all turned out well,” Winnie says.

Amazingly, her girl has turned out to be an amazing singer and would like to pursue a career in music. She also loves acting and experiment with make-up.

“She is anxious to unravel what the future brings forth! I would advise parents not to lose hope whenever they find themselves in such a situation. Help is there and a smile will be restored,” says Winnie.

A cleft lip, which is a split in the upper lift, and a cleft palate, a split in the roof of the mouth, is formed if the tissue doesn’t fuse together in the way it should during the fourth to seventh week of pregnancy. A child could have one or the other, or both.

“Cleft lip and palate is more than just the physical health condition. There are other issues to deal with. They range from nutritional challenges as children with this condition struggle with breastfeeding, which is essential in their early years,” explains Dr Martin Kamau the Co-Founder and lead maxillofacial surgeon at Bela Risu Medical Centre (BMC), a cleft lip and palate-only health facility in Nairobi.

Due to the existing health systems, cleft lip and palate treatment remains a challenge as it is not prioritised in many countries’ health policies. As such, the medical outreaches are spontaneous and only serve those who can access the periodic medical camps, he says.

With 47 counties in Kenya, it requires more targeted and continuous medical camps to reach everyone who needs this service. This, however, leaves a gap on subsequent medical enquiries and follow-ups.

Comprehensive care

It is this gap that inspired Dr Martin and his co-founder to seek a permanent solution; a facility that would offer comprehensive care not only for patients, but also to their families who often face stigma and stress. “In 2017 we saw this space and decided to do something to ensure continuity of care and fully connect to the patients.”

After some years of outreach in remote parts of Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Angola and Bangladesh, BMC experienced challenges in effective follow-up and possible dropout by patients who needed consistent medical attention post surgery.

This comprehensive care centre consists of two theatres and 25 beds to handle speech therapy, dental alignment, nutritional advice, and facial deformities.

Dr Martin refers to it as the brick and mortar of the cleft and palate treatment and care where the team treats the visible (cleft and palate) and the invisible (the associated stigma of the condition).

Teaching communities to ‘fish’

While medical outreaches play a critical role in taking the services of cleft lip and palate repair to the remotest parts of the African continent, the ability by local communities and health professionals to own the solutions to this challenge remains paramount.

To achieve this, BMC’s Education and Training equips local healthcare providers with comprehensive hands-on surgical training. In May this year, the team trained six maxillofacial residents at the Central Hospital of Lubango, Angola.

Dr Martin recounts the instances that have left him glued to the mission of putting a smile on the face of cleft patients: “My most memorable case was in 2014 in Butembo, North Eastern Congo. We conducted surgeries under the Central Church of East Africa. Although we travelled with the anesthetist, we never had any equipment and relied on theirs. We conducted about 20 surgeries in about two days,” he recounts.

He narrates about the community’s act of appreciation that inspired the BMC team to keep up the work they do to date: “We stepped out of the operation room to find mothers dancing outside in appreciation. It occurred to me and my anesthetist that we were a huge inspiration and source of hope to these families,” he beams with joy.

In Kenya, approximately one in every 500 babies is born with a cleft lip or cleft palate yet there are many children who never receive life-changing surgery.

In many instances, such as in Winnie’s case, women are often irrationally blamed when a child is born with clefts. Women are accused of unfaithfulness, or that she had a failed abortion, that she somehow cut the child’s face, or that she was cursed.

Due to difficulties with breastfeeding, malnutrition among children with clefts is heightened. Without adequate nutrition in these critical months and years of development, babies and children with clefts often become underweight and at risk of growth failure and death.

Given this, babies with clefts need increased nutritional support in order to ensure they are healthy and able to undergo surgery to fix their cleft safely.